Chapter 9

Peter, James, and Paul

The Original Appearance to Peter

We have now traced an unbroken line from ancient polytheistic Israelite religion → Persian-established monotheistic Judaism → various sects of Judaism active as the first century CE began. We’ve seen that one of these main sects of Judaism then became distinct from the others in its adoption of a great many additional doctrines imported from Zoroastrianism that inspired their many apocalyptic writings. And we have now connected these Zadokites/Essenes with the earliest Christian writings both in terms of unique theology, worldview, rituals, doctrines, areas of concern, and specific language.

If, as it would seem, Christianity did not start with a historical person named Jesus of Nazareth, can another specific person be named as the founder of this new religion? Though the epistles of Paul are the earliest known Christian writings, it is clear from his own writings that Paul himself did not found the religion that he is preaching. Paul identifies himself as an “apostle”, but also acknowledges that he was the last among all the apostles to whom Christ appeared.11 Corinthians 15:7-8. The Bible. New International Version. Paul’s specific choice of words concerning these “appearances” are noted by scholars of ancient Greek to be those someone would use to describe visionary experiences rather than seeing someone in person, and this applies not just to his own experience, but also when he is describing the “appearance” of Jesus to the others who came to the faith before him.2Doherty, E. (2005.) The Jesus Puzzle: Did Christianity Begin with a Mythical Christ? Age of Reason Publications. At one point when he provides a list of apostles to whom The Lord appeared, the only specific names he supplies are that of a man named Peter (the Greek form of “Cephas” in Aramaic) and another named James.31 Corinthians 15:3-8. The Bible. New International Version.

Elsewhere in his letters, Paul also speaks of a trio of men named James, Peter, and John, with whom he has occasional interactions. He refers to these three men as the “pillars”,4Galatians 2:9. The Bible. New International Version. and it is clear from context that they are authority figures within the movement Paul has joined as a late-comer, and he may even see them as the founders of the sect. In addition, Paul also lists an appearance of Christ to a collective he calls “The Twelve”,51 Corinthians 15:5. The Bible. New International Version. but never names any individual members of this group or gives any indication of the meaning of this designation. Given the great many overlaps we have noted between Essenes and earliest Christians though, and given that we saw that the Dead Sea Scrolls also describe the highest governing body of their community as consisting of three priests called “pillars” and a council of twelve men, it is hard to escape the conclusion that Christianity sprang directly from the Essenes.

We can go a little farther than this. Several later Christian writings portray this James figure as the very first leader of the church in Jerusalem, sometimes referring to him as “James the Just” (equivalent of “James the Righteous” or “James the Zadokite”). In line with being an Essene leader, James is described as abstaining from all alcohol, eating no meat, using no ointments, and never cutting his hair. He is also one of the few figures connected to earliest Christianity who is mentioned outside the Bible by a historian of the time who wrote concerning a “James the Just”, who is described as a very popular and influential religious leader among the people of Judah in the 50s CE.

James is not described as a “Christian” by the historian, but that term was not used among the earliest believers. The term “Essene”, in fact, was actually a name only used by outsiders when referring to the sect. The self-designations they used varied but strikingly overlapped with those of the earliest Christians, including The Way, The Poor (“Ebionites”), The Saints, and The Ekklesia (“church”).6Magee, M.D. Christianity Revealed: Christianity and the Essenes. AskWhy! Productions. James would first and foremost have been seen by his contemporaries as a fanatically devout Jew, obsessed with keeping every facet of the Law of Moses and mastering his emotions to avoid sin. His idiosyncratic views concerning the messiah would not have prominently stood out since, as already noted, the messianism of the Jewish people at this time, though fevered, was not especially focused and certainly not anything like settled dogma.

When Paul wrote of an associate who was caught up to the third heaven in a vision 14 years ago, this is likely a reference to Peter whom he credits as being the first person to whom Jesus appeared.71 Corinthians 15:5-8. The Bible. New International Version. While we can’t know the exact content of this vision, we get a rough idea from the theology presented by Paul’s letters and The Ascension of Isaiah since they represent the earliest known distinctly Christian theology and worldview. Peter, as we’ve seen, was very likely one of the three pillars of the Essene community, and would surely have excitedly shared his amazing vision, first with the other two pillars James, and John, and then with rest of the brothers in the community.81 Corinthians 15:5-8. The Bible. New International Version. All of them, writes Paul, soon had their own appearances of Jesus, and a new religion was born.

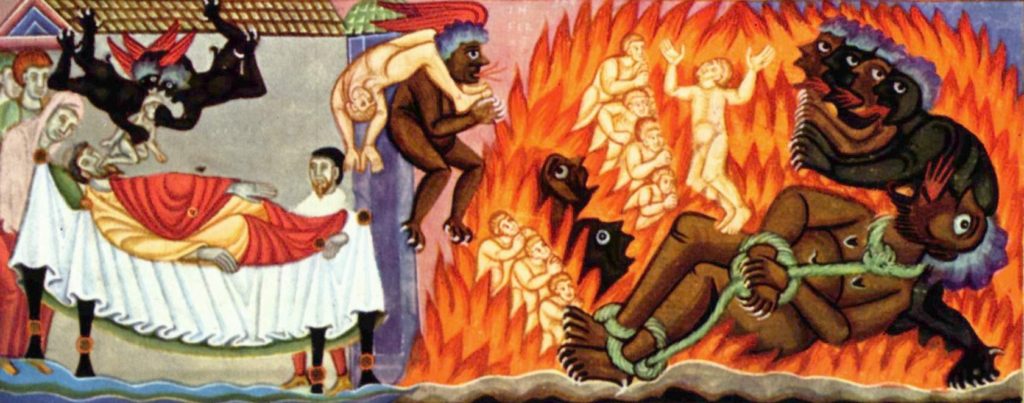

We can’t know exactly how novel the content of Peter’s vision was. While key details like existence of Lord Jesus, his crucifixion and subsequent raising from the dead may well have originated with Peter. On the other hand, it’s possible that The Ascension of Isaiah predates the appearance of Jesus to Peter, and that his transformative vision simply verified its contents, convincing him that now, on the eve of the End Times, he and his brethren must announce the existence of the savior Christ to all Jews. It was an urgent message, for one notable constant through all early Christian writings is the absolute conviction that the End Time would arrive within the lifetime of the writer. The time left to avoid damnation was rapidly running out.

The very idea of apostles (literally “one who has been sent out” to spread a message, e.g.) implies a significant change took place at this time among the Essenes. The community that had intentionally separated itself from society and seemed to stay generally inward-looking, now began to disseminate a message to their fellow Jews that they saw as profoundly vital. The same community that had traditionally required an incredibly strict three-year initiation period to join the fold was now actively proselytizing with more minimal membership requirements in what they believed were the final days before the cataclysmic end. Even the public-facing ministry of John the Baptist demonstrates such a change was underway by 30 CE.

A Crucified Messiah

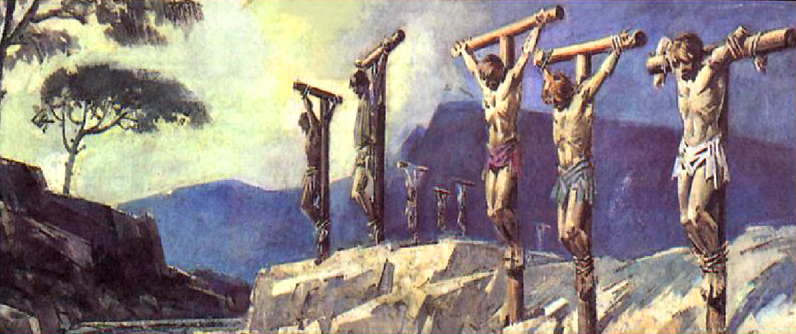

Assuming it’s correct that Jesus of Nazareth was not a historical person executed by Roman authorities, we are left to ask: why would Peter’s vision have been of a heavenly messiah who was killed and very quickly restored back to life? And of all the methods by which he could die, why crucifixion specifically? We can’t know the answers to these questions with certainty—some aspects of visionary experiences are merely fantastical and random like the content of dreams—but there are some considerations worth noting.

Though we can’t know what level of knowledge Peter possessed concerning other dying-and-rising deities popular in his day, it’s certainly worth pointing out that they were quite popular throughout the Roman Empire at this time, and each variation on such a god was believed by their followers to have undergone a particular and notably non-heroic death, suffering through a “passion” (the same word adopted by Christians) before triumphantly returning to life and thereby ensuring the future resurrection and salvation of their adherents. Adonis was believed to have been killed by a beast, Dionysus was dismembered, Attis cut off his own testicles and bled out.

Similar to crucifixion, these are not triumphal deaths by any means. When the first-known dying-and-rising Sumerian god, Inanna, was killed, her corpse was “hung on a nail” for three days before being resurrected, whereupon she was fed the “water and food of life” to revive her.9Leick, G. (2002). A Dictionary of Ancient Near Eastern Mythology. Routledge. Glory and triumph were achieved by their passing through these humbling ordeals, with each such god returning to life massively empowered to save believers.10Carrier, R. (2020). Jesus from Outer Space: What the Earliest Christians Really Believed about Christ. Pitchstone Publishing.

From writings found among the Dead Sea Scrolls, we know that the Essenes were fanatically anti-Roman and looked forward to a world-ending war against the empire in the Last Days.11Vermes, G. (2004). The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English. Penguin UK. We also know that the Essenes—like their Zadokite predecessors and the Maccabees—celebrated the act of martyrdom, and would pass that trait on to early Christianity. We know as well that the standard Roman punishment for any act of rebellion against the state was death by crucifixion. It may well be that these three facts best explain why the leader of the Essenes would see glory and great meaning in the messiah’s willingness to undergo crucifixion as a martyr, thereby (through some mysterious means) guaranteeing salvation to those who believe in it. Having their heavenly savior set such an example for his adherents does have a certain logic.

We further know that the Essenes of this time, particularly their Teacher of Righteousness, were combing through the Jewish scriptures for out-of-context passages they interpreted as revealing secret information about the coming messiah.12Qumrān literature (Dead Sea Scrolls). Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/biblical-literature/Qumran-literature-Dead-Sea-Scrolls#ref597947 It could be that Peter had his vision of Lord Jesus being crucified first and then afterward sought to find passages in scripture which supported the veracity of his vision. Conversely, it may have happened in the opposite order—Peter’s regular and intense scrutinizing of scripture may well have shaped the nature of his world-changing religious vision.

The Psalms and the book of Isaiah were the two scriptures most poured over by both the Essenes and the earliest Christians. The single verse from Psalms that may be most responsible for suggesting a death by crucifixion was verse 22:16, which states “the assembly of the wicked has surrounded me and pierced my hands and feet.” That this was a redemptive death found support in verses pulled from Isaiah 53 which speaks of:

- “a man of suffering”

- who “took our pain and bore our suffering”

- who “was pierced for our transgressions”

- who was “led like a lamb to the slaughter”

- “It was Yahweh’s will to crush him and cause him to suffer”

- “Yahweh makes his life an offering for sin”

- “The righteous servant will justify many and bear their wickedness”

- “He poured out his life unto death”

- “bore the sin of many, and made intercession for the transgressors”

- “by his wounds we are healed”

These quotes, written hundreds of years beforehand—not by the original author of Isaiah, but by a later writer pretending to be Isaiah—were, of course, not written with some future messiah in mind, but were most likely predictions about King Hezekiah of Judah, a relevant figure, as we have seen, at the time of the prophet Isaiah. Interestingly, a copy of the book of Isaiah found among the Dead Sea Scrolls has a unique quirk in that it twice used the word “pierced” instead of the original word “bruised”, so that instead of “he was bruised for our transgressions” it reads “he was pierced for our transgressions”—far more suggestive of crucifixion.13Isaiah 53. The Bible. New International Version.

Paul of Tarsus

The man known to us as the Apostle Paul was born in the Greek-style city of Tarsus in the southeast of what is today Turkey. Greek was his first language. He was raised in the Pharisee sect—by this point as known for their history of accommodation to foreign overlords as much as their synagogue leadership and their unique tradition of the Oral Law. Paul appears to have been a member of the family of the brother of the late tyrant Herod. Among several pieces of evidence to support this notion are his Roman citizenship—quite rare for a Jew—and his being in a position of power at a young age.14Eisenman, R.H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin.

Early in his career, Paul is tasked by the High Priest in Jerusalem with carrying out attacks against what he refers to in his letters as the “ekklesia of God”—what we would, in retrospect, call the first Christians—who at this point have been viewed by their countrymen as a fanatical sect of fellow Jews with a peculiar theology of the messiah. But the content of their theology by itself would not have been seen as a threat that required violent suppression—as we’ve seen, Jews of the time had greatly varying views of the expected messiah. The dire threat they presented, as with any fanatical messianic group of the era, was their potential for militancy that would lead to revolt against the Jewish aristocracy, the high priest, and their Roman overlords—whose retaliation could destroy not merely the status quo, but the entire nation.

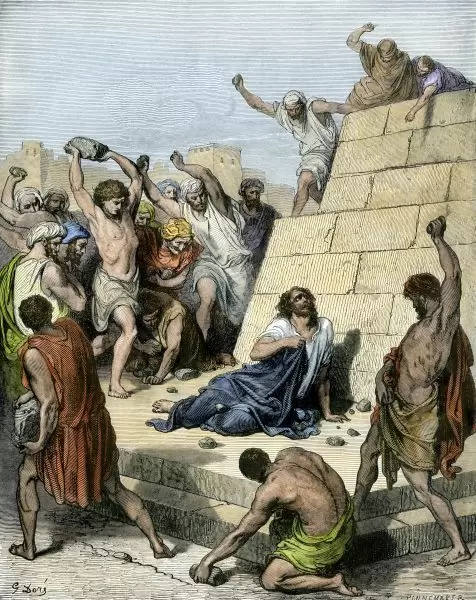

In his epistles, Paul readily admits to carrying out these intense persecutions aimed at destroying the movement,15Galatians 1:13. The Bible. New English Translation. while the book of Acts portrays Paul doing great harm to “the Saints” in Jerusalem, going from house to house, dragging people off, and throwing them in prison.16Acts 26:10-11. The Bible. New International Version. He is portrayed as approvingly standing by as a believer is stoned to death.17Acts 8:1-3. The Bible. New International Version. And he “threatens the apostles of the Lord with murder”.18Acts 9:1-2. The Bible. New International Version.

The Acts of the Apostles, and, obviously, the letters of Paul himself relate events of this period from the perspective of Paul and his supporters. Composed 80 to 100 years after these events, scholars have long recognized that one of the main goals of the writer of Acts is to whitewash history and convince the reader there was complete harmony in the earliest church.19 Pervo, R.I. (2008). The Mystery of Acts: Unraveling Its Story. Polebridge Press. Peter is portrayed as agreeing with Paul on every doctrine. James is sidelined completely, becoming a very minor character, despite it still being obvious that he is the original leader of the Jerusalem church—the bishop of bishops, as a later, more deferential Christian would remember him.20Eisenman, R.H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin.

While the New Testament does not provide us with accounts of the earliest church from the perspective of Peter or James, it is clear that their followers did create such writings. Some of these are only known through the works of later church elders who quoted the material in their own writing—the original documents have been lost to time or intentionally destroyed. But a fascinating work known as The Memoirs of Clement survives to this day. It purports to be written as a firsthand report by Flavius Clemens (also known as “Clement”), a high-ranking noble in Rome. In the writings of a Roman historian of the time, this same Clement is mentioned in a list of notable people in Rome who converted to Judaism around this time (before “Christianity” had become a differentiating term).21Eisenman, R.H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin.

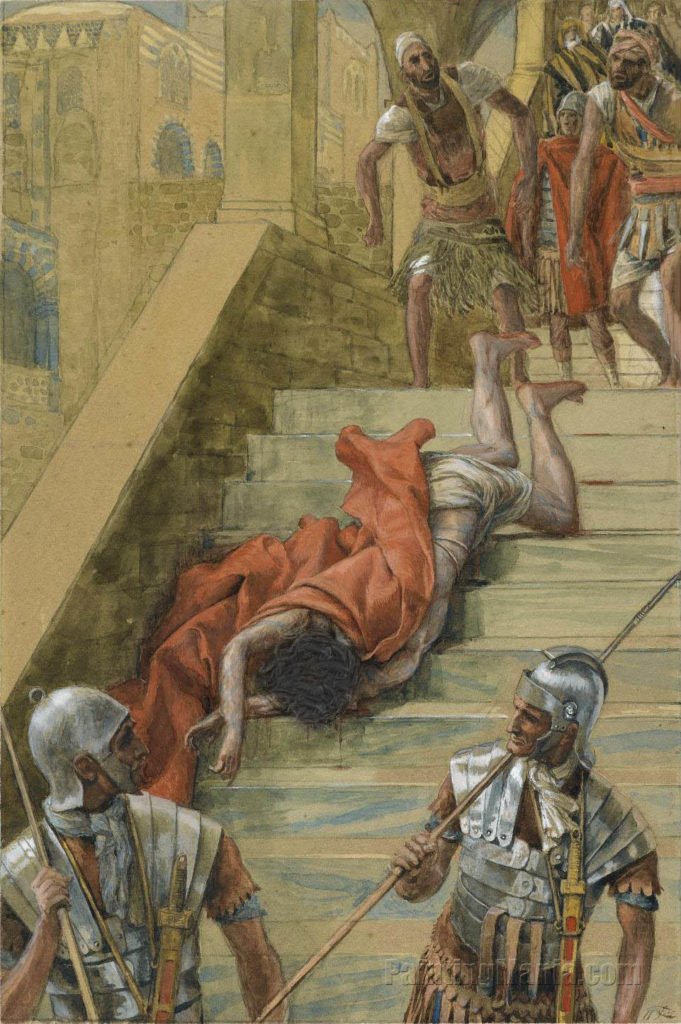

In the Memoirs, Clement relates that, having heard the preaching of a certain Jew named Barnabas in Rome, he followed him back to Judah where he was introduced to Peter and James. Over an extended period of time, Peter becomes Clement’s mentor. At one point he tells Clement a story about a fateful confrontation that occurred at the Jerusalem Temple years ago which went as follows: James the archbishop of the church, Peter, and the whole ekklesia were in the Jerusalem Temple, preaching and proselytizing for seven straight days to their fellow Jews. They had just convinced the crowds and even the high priest to become baptized when, just then, Peter relates that “some of our enemies” arrived and began shouting against them, drowning out James’s voice as he attempted to refute them. At this point, “that enemy”—identified as Paul—rants against them like a madman, inciting the crowds into a murderous rage against Peter and James. Paul then shouted to the crowd, “What are you doing? Why do you hesitate with sluggishness? Why don’t we grab these men and tear them to pieces?” Then Paul grabbed a branch of wood from the altar to lead the attack. In a scene of chaos, many were beaten bloody while attempting to escape, and Paul is said to have pushed James headlong down a flight of steps, leaving him for dead.22Eisenman, R.H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin.

His legs broken, James is carried away to safety, and the next day he and a great multitude of believers head to the area of Jericho—which is close to the Essene camp where the Dead Sea Scrolls were later discovered. It is unclear how crippling this attack was on James. The text only notes that some time later he was still limping on one foot. Paul, for his part, is now said to have rushed off toward Damascus to track down Peter whom he believes has fled there.23Eisenman, R.H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin. While none of this material can be taken at face value as historical, it would seem on equal footing with the book of Acts which was written around the same time but by those in Paul’s camp.

Acts agrees that Paul’s persecution forced the community to scatter across Judah and Samaria. It says he then received permission from the high priest to travel to Damascus to capture and imprison all those of “The Way”. It is at this time, according to Acts, that Paul had his life-changing (world-changing we might say) conversion experience.24Acts 9:1-9. The Bible. New International Version. In his epistles, the account Paul provides of his conversion lacks any of the theatrics later described by the author of Acts. His account is actually completely devoid of any detail, with Paul looking back on it simply as the moment “when the one who set me apart from birth and called me by his grace was pleased to reveal his Son in me so that I could preach him among the Gentiles” (non-Jews). Paul only tells us that immediately after his conversion he did not consult with any human beings, and did not go to Jerusalem to see those who were apostles before him. Instead, he says, he traveled to Arabia and then back to Damascus. His reference to “Arabia” here is vague since in this period the term was used to describe a swath of land stretching much farther north than how we use the term today. 25Galatians 1:15-17. The Bible. New International Version.

Exactly where in Arabia he rushed off to, why, and who he met there or in Damascus is unclear. Paul says that it was a full three years after his conversion that he finally came to Jerusalem. Since three years is the exact amount of time it would take a prospective member to go through the strict Essene initiation, it’s quite possible that Paul spent this time at an Essene community in the vicinity of Damascus. Only at the end of that long period of time does Paul come to Jerusalem where he says he spent fifteen days staying with Peter and saw no other apostles there, but did see James. He then departs to Syria and Cilicia (in modern day Turkey).26Galatians 1:15-21. The Bible. New International Version. Paul further says he did not return to Jerusalem again for the next 14 years. 27Galatians 2:1. The Bible. New International Version.

The Epistle of James

Just how closely Paul’s worldview ever matched that of James, Peter, and the Essenes is unclear. While we have seven surviving epistles written by Paul, the New Testament contains only one epistle by James. Historians—especially Christian historians—have long questioned the authenticity of the letter attributed to James due to the difficulty they face in accepting that the first leader of the ekklesia in Jerusalem could be so focused on and insistent that his fellow believers obey every letter of the Laws of Moses, even insisting this is absolutely necessary for salvation.28James 4:11-12. The Bible. New International Version. Yet if we take the perspective that James was the leader of the Essenes as they transitioned into “Christians”, this is exactly what we would expect.

James addresses his letter to Jews living abroad. Just as Paul does in his letters, James refers to himself as “a slave of God and the Lord Jesus Christ” and mentions “faith in our glorious Lord Jesus Christ”, but he does not lay out his theology. Instead he focuses on issues we would expect from an Essene leader. As noted above, he obsesses over the necessity to follow every aspect of The Law of Moses in order to attain salvation, writing “One who obeys the whole law except for a single point becomes guilty of all of it”.29James 2:10. The Bible. International Version. While he stresses the importance of faith without room for doubt, he makes clear that faith alone without proper actions (ie. obedience to the Law) is useless and will not lead to salvation,30James 2:14-17. The Bible. New International Version. and he writes that “Pure and undefiled religion before God the Father is this: to care for orphans and widows in their adversity and to keep oneself unstained by the world.”31James 1:27. The Bible. New International Version.

Like Essene writers, James identifies his community as The Poor and rails against the rich, writing “Did not God choose The Poor in the world to be rich in faith and heirs of the kingdom that he promised to those who love him?”; “Are not the rich oppressing you and dragging you into the courts?”,32James 2:5-6. The Bible. New International Version. likely referencing those aristocratic Jews like Paul before his conversion, who were attempting to suppress communities like James’s with brutal violence. Finally, toward the end of his epistle, James unleashes a tirade: “Come now, you rich! Weep and cry aloud over the miseries that are coming on you. Your riches have rotted and your clothing has become moth-eaten. Your gold and silver have rusted and their rust will be a witness against you. It will consume your flesh like fire. It is in the Last Days that you have hoarded treasure! Look, the pay you have held back from the workers who mowed your fields cries out against you, and the cries of the reapers have reached the ears of the Lord of Heaven’s Armies”,33James 5:1-5. The Bible. New International Version. adding that “Judgment is merciless for the one who has shown no mercy.”34James 2:13. The Bible. New International Version.

Within the community, again mirroring the Dead Sea Scrolls, James urges fellow believers to master their emotions and show to one another love, reminding them to be “quick to listen and slow to anger.” He quotes Leviticus 19:18, which he calls the Royal Law: “You shall love your neighbor as yourself”,35James 2:8. The Bible. New International Version. and further instructs, “Do not speak against one another, brothers. He who speaks against a fellow believer or judges a fellow believer speaks against The Law and judges The Law. If you judge The Law, you are not a doer of The Law but its judge. But there is only one who is lawgiver and judge—the one who is able to save and destroy. On the other hand, who are you to judge your neighbor?” 36James 4:11-12. The Bible. The New International Version.

And finally, again matching Essene concerns over fornication and separation from the polluting sins of society in general, James asks: “Adulterers, do you not know that friendship with the world means hostility toward God? So whoever decides to be the world’s friend makes himself God’s enemy.”37James 4:4 The Bible. New International Version. He advises his readers to “put away all filth and evil excess and humbly welcome the message implanted within you, which is able to save your souls.”38James 1:21. The Bible. New International Version. Presumably this message is the core gospel (“good news”) he and Paul hold in common: the existence of a heavenly savior who has at long last been revealed to a select few chosen apostles who are tasked with spreading the message of salvation far and wide in these Last Days.

Though, as noted, his single epistle does not provide details of his theology, one phrase used by James warrants mention. He refers to God as “The Father of Lights in whom there is no variation or the slightest hint of change”.39James 1:17. The Bible. New International Version. The “of Lights” descriptor seems to reference the doctrine of “the Forces of Light forever in contention with the Forces of Darkness” seen in the Dead Sea Scrolls, The Book of Watchers, and the Enoch Apocalypses (and which was, like so much else, originally adopted from Zoroastrianism). But the descriptor “in whom there is no variation or the slightest hint of change” concerning God smacks of influence from the likes of Philo Judaeus of Alexandria and his unchanging, unreachable, ineffable God who requires a heavenly Logos or Son of God to act as intermediary.

Like Paul’s letters and all other earliest Christian writings, James’s epistle betrays absolutely no inkling of knowledge that a human Jesus walked the Earth within his lifetime, much less that James walked with him as a disciple. Nor does his letter in any way support later tradition’s notion that James was Jesus’s own brother. As with all other earliest Christians, James never quotes Jesus’s sayings—even when he writes about topics that the gospels record Jesus as having spoken directly about. None of the people, places, parables, miracles, or actions familiar to us from the gospels are either mentioned or alluded to.

One point of overlap between Paul’s epistles and that of James is their urging of their communities to stand fast in the face of persecution, arguing that this is what defines one’s character, and that such actions will be rewarded with salvation and an afterlife with God in Heaven. But when James uses examples of martyrs who bore their sufferings with grace, he mentions the prophets of old who—in his interpretation—spoke of the coming messiah,40James 5:10-11. The Bible. New International Version. but he does not use the one example we would surely expect if James knew of a Jesus crucified on Earth just a few years earlier, which is to say: Jesus himself, who surely would have been the most obvious and greatest example of a revered figure who bore persecution for the sake of greater glory.

The Epistle of Peter

Of the two letters in the New Testament attributed to Peter, scholars universally recognize the second to be a later forgery. 1 Peter is also generally not considered authentic,41Ehrman, B.D. (2011). Forged: Writing in the Name of God—Why the Bible’s Authors Are Not Who We Think They Are. HarperOne. but the traditional reasoning is that the epistle’s relatively polished writing style doesn’t square with Peter being a simple rural fisherman—the portrayal of him that is introduced decades later in the gospels. The actual historical Peter, as we’ve seen, however, was most likely a high level leader among the Essene sect—which produced a great many well-written documents, and which—as is becoming clearer and clearer, transitioned to become the earliest Christian community in Jerusalem.

As with all earliest Christian writers, Peter too betrays no sign he is aware of a Jesus who had very recently walked the Earth—much less that this messiah was one of his closest companions throughout his ministry. He writes nothing to indicate he was an eyewitness to any teachings, exorcisms, healings, or other miracles, and never offers a single quote from Jesus. Although occasional sayings or biographical-sounding details for Jesus are mentioned, in every instance the source provided for these is not Peter himself—or any other human’s recent memory of Jesus’s time on earth. Rather, all of this information is derived exclusively from quotes from the Hebrew scriptures removed from their original context.

In fact, Peter explicitly mentions that the scriptures were carefully probed, searched, and investigated for information about the sufferings that the messiah would undergo and about his subsequent glory.421 Peter 1:10-11. The Bible. New International Version He tells his readers to prepare themselves for the time “when Jesus Christ is revealed” (not “returns”).431 Peter 1:7. The Bible. New International Version. Jesus, he writes, has existed since the foundation of the world, but only made known now in the Last Days.441 Peter 1:4-5. The Bible. New International Version. Peter writes “You have not seen him, but you love him. You do not see him now, but you believe in him, and you rejoice” “because you are attaining the goal of your faith—the salvation of your souls”.451 Peter 1:8. The Bible. New International Version. Nowhere here does Peter imply that he himself or other apostles have, by contrast, seen Jesus in person during his recent ministry.

He warns that believers may have to suffer various trials before their salvation, but that such trials will prove the character of their faith. This may refer to the persecution from Jewish authorities like that dealt out by the murderous pre-conversion Paul, or it may refer to expected suffering at the tribulations of the End Times, or both.461 Peter 1:6. The Bible. New International Version. Satan, cautions Peter, is like a roaring lion on the prowl for someone to devour, so they must remain sober, alert, maintain proper conduct, and keep away from fleshly desires.471 Peter 5:8-9. The Bible. New International Version.

One bit of theology found in 1 Peter that is unique among early Christian writings is the notion that immediately after his death, before ascending back to heaven, Jesus went to “the imprisoned spirits” who were disobedient in the time of Noah, and made a proclamation.481 Peter 3:18-20. The Bible. New International Version. The meaning of this is not entirely clear. Was Peter referring to the Watchers who impregnated human women who bore a race of destructive giants and were then imprisoned by God? Or does this refer to those humans who were disobedient and therefore drowned in the Flood and are now in Hell? Either way, the source of this idea seems to be another out-of-context passage from Isaiah which states: “It shall come to pass in that day, that Yahweh shall punish the host of the high ones that are on high, and the kings of the earth upon the earth. And they shall be gathered together, as prisoners are gathered in the pit, and shall be shut up in the prison, and after many days shall they be visited.”49Isaiah 24:22-23. The Bible. New International Version.

Until the cataclysms of the final days arrive, Peter urges his listeners to remain compliant to those in authority.501 Peter 2:13-14. The Bible. New International Version. The young are to be subject to the elders. Wives are to treat husbands as their lords and not to adorn themselves.511 Peter 3:1-3. The Bible. New International Version. Slaves are to show respect and obedience to their masters, even those who are cruel, for those who suffer unjustly share in the sufferings of Christ.521 Peter 2:18-21. The Bible. New International Version. Among members of their religious communities, Peter urges compassion and humility, and to refrain from reciprocating insults or evils.531 Peter 3:8-12. The Bible. New Internatio

The epistle ends with Peter sending his audience greetings from the church in “Babylon”,541 Peter 5:13. The Bible. New International Version. which, as in the book of Revelation, is apparently a nickname or codeword for Rome. If so, it is the only real evidence that Peter ever visited the capital of the empire—other than the many late and conflicting traditions of his preaching and martyrdom there, none of which are substantiated. From Paul’s letter to the Romans, however, it is clear that a community of believers had been established there before his own arrival there. We also know that Peter was a traveling apostle, we just don’t know much about his itineraries.

Continue Reading:

Chapter 10: Inclusion of the Gentiles

Footnotes

- 11 Corinthians 15:7-8. The Bible. New International Version.

- 2Doherty, E. (2005.) The Jesus Puzzle: Did Christianity Begin with a Mythical Christ? Age of Reason Publications.

- 31 Corinthians 15:3-8. The Bible. New International Version.

- 4Galatians 2:9. The Bible. New International Version.

- 51 Corinthians 15:5. The Bible. New International Version.

- 6Magee, M.D. Christianity Revealed: Christianity and the Essenes. AskWhy! Productions.

- 71 Corinthians 15:5-8. The Bible. New International Version.

- 81 Corinthians 15:5-8. The Bible. New International Version.

- 9Leick, G. (2002). A Dictionary of Ancient Near Eastern Mythology. Routledge.

- 10Carrier, R. (2020). Jesus from Outer Space: What the Earliest Christians Really Believed about Christ. Pitchstone Publishing.

- 11Vermes, G. (2004). The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English. Penguin UK.

- 12Qumrān literature (Dead Sea Scrolls). Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/biblical-literature/Qumran-literature-Dead-Sea-Scrolls#ref597947

- 13Isaiah 53. The Bible. New International Version.

- 14Eisenman, R.H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin.

- 15Galatians 1:13. The Bible. New English Translation.

- 16Acts 26:10-11. The Bible. New International Version.

- 17Acts 8:1-3. The Bible. New International Version.

- 18Acts 9:1-2. The Bible. New International Version.

- 19Pervo, R.I. (2008). The Mystery of Acts: Unraveling Its Story. Polebridge Press.

- 20Eisenman, R.H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin.

- 21Eisenman, R.H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin.

- 22Eisenman, R.H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin.

- 23Eisenman, R.H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin.

- 24Acts 9:1-9. The Bible. New International Version.

- 25Galatians 1:15-17. The Bible. New International Version.

- 26Galatians 1:15-21. The Bible. New International Version.

- 27Galatians 2:1. The Bible. New International Version.

- 28James 4:11-12. The Bible. New International Version.

- 29James 2:10. The Bible. International Version.

- 30James 2:14-17. The Bible. New International Version.

- 31James 1:27. The Bible. New International Version.

- 32James 2:5-6. The Bible. New International Version.

- 33James 5:1-5. The Bible. New International Version.

- 34James 2:13. The Bible. New International Version.

- 35James 2:8. The Bible. New International Version.

- 36James 4:11-12. The Bible. The New International Version.

- 37James 4:4 The Bible. New International Version.

- 38James 1:21. The Bible. New International Version.

- 39James 1:17. The Bible. New International Version.

- 40James 5:10-11. The Bible. New International Version.

- 41Ehrman, B.D. (2011). Forged: Writing in the Name of God—Why the Bible’s Authors Are Not Who We Think They Are. HarperOne.

- 421 Peter 1:10-11. The Bible. New International Version

- 431 Peter 1:7. The Bible. New International Version.

- 441 Peter 1:4-5. The Bible. New International Version.

- 451 Peter 1:8. The Bible. New International Version.

- 461 Peter 1:6. The Bible. New International Version.

- 471 Peter 5:8-9. The Bible. New International Version.

- 481 Peter 3:18-20. The Bible. New International Version.

- 49Isaiah 24:22-23. The Bible. New International Version.

- 501 Peter 2:13-14. The Bible. New International Version.

- 511 Peter 3:1-3. The Bible. New International Version.

- 521 Peter 2:18-21. The Bible. New International Version.

- 531 Peter 3:8-12. The Bible. New Internatio

- 541 Peter 5:13. The Bible. New International Version.