Chapter 3

The Maccabean Revolt

The Greek Period

In 334 BCE, a young king from northern Greece named Alexander led an army into Asia Minor, invading the lands of the vast Persian Empire. In a rapid succession of battles and sieges, his Greek army seized control of the Levant and Egypt. Having heard harrowing reports of the fate of the powerful Phonecian city of Tyre that had resisted Alexander’s army in a protracted siege, Jerusalem’s leaders resolved to open their gates in a preemptive surrender, falling at his mercy. Their decision kept the city and its people from destruction.1Heckel, W. (2008). Alexander the Great: A New History. Wiley.

Alexander annexed all of Judah and his army would then spend the next two years progressively taking control of all the lands of the now defeated Persian Empire, as far east as the borderlands of India.2McCarty, Nick (2004). Alexander the Great. Camberwell, Victoria: Penguin. Like many Greeks, Alexander held Persian civilization in high regard, and wished to be seen as a legitimate Persian ruler. He also thought much of his own culture, and throughout the lands he conquered, he established cities in the traditional Greek style. He hoped that his massive empire would mesh the best qualities of these and other cultures.3Green, Peter (2007). Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Age. London: Phoenix.

But Alexander unexpectedly died from illness at age 32. With no secure heir, his empire immediately fractured as his top generals Ptolemy, Seleucis, and others battled for control. Judah now found itself perilously positioned on the contested border between the two most formidable of these new powers.

Between 300 and 200 BCE the Judahites lived as part of the Greek-controlled Ptolemaic kingdom of Egypt whose capital was the newly-established city of Alexandria. It was during this period that the Great Lighthouse of Alexandria was constructed.4Bartlett, J. R. (2011). Between Alexander and Antiochus: Jews and Judaeans in the Hellenistic Period. Eisenbrauns.

Then after a series of wars, in 200 BCE, control of Judah passed to the sprawling Greek-controlled Seleucid Empire, whose capital was at Antioch on the border of what is today Syria and Turkey.5Charles River Editors. (2019). The Seleucid Empire: The History of the Empire Forged in the Ancient Near East After Alexander the Great’s Conquest. Independently published.

The High Priesthood Crisis

During this era of Alexander’s successors’ control over the eastern Mediterranean, Greek language and culture became widely adopted—strictly on a voluntary basis—especially by the upper class and ruling parties of their subject lands.

The widespread construction of amenities typical of a Greek city—including schools, theaters, stadiums, gymnasia, baths, hippodromes (chariot racing arenas), agoras (marketplaces), and other grand public buildings—enhanced the reputation of local rulers and provided benefits welcomed by the vast majority of these cities’ residents. Judah was by no means an exception, and relations between the Jews and the Seleucids were generally congenial for the first years of their overlordship until things changed rather suddenly.6Coogan, M. A. (2002). Between Alexandria and Antioch: Jews and Judaism in the Hellenistic Period. Oxford University Press.

As a subject people without a king, it was the high priest of Jerusalem who had long been the most powerful and influential figure in Judah. The office was hereditary, and—whether accurate or not—their lineage was traced in an unbroken chain back to the legendary days of King David who is said to have elevated a man named Zadok (meaning “Righteous” or “Just”) to the office. As a result, Zadokite family control over the high priesthood was traditionally believed to have lasted unbroken through centuries, even purportedly managing to survive the 70 year period of captivity in Babylon.7Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

In 187 BCE, a Zadokite man named Onias III rose to the high priesthood. Whereas he was a zealous traditionalist opposed to excesses in the adoption of Greek ways, it so happened his brother Jason had no such qualms. And when a new Seleucid emperor named Antiochus IV came to power in 175 BCE, the scheming Jason accessed a large sum of money from the Temple treasury and used it to successfully bribe the new emperor to install him as a new high priest in place of his brother.8Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

Having been deposed, the rightful high priest Onias immediately fled Jerusalem and made his way north to the Seleucid capital of Antioch is Syria, where the local Jewish population petitioned on his behalf for his reinstatement. But rather than assist him, Emperor Antiochus IV had Onias murdered. But the usurper Jason’s reign as high priest was brief. Almost immediately, he got a dose of his own medicine when an even more unscrupulous man named Menelaus outbid him using even more of the Temple’s treasures as a bribe, and was thus awarded the high priesthood in his place. Though the usurpring Jason had at least been of proper Zadokite lineage—and thus eligible for the office of high priest—this Menelaus was not even from a priestly family.9Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

And thus the extraordinarily long line of Zadokite high priests now came to an end. This high priesthood legitimacy crisis had a deeply fracturing effect on Jewish society. Aghast that the true high priest Onias III had been bribed out of office and murdered, many traditionalist Jews became fanatic in their opposition to the Seleucids and their new Greek-culture-promoting illegitimate puppet high priest Menelaus.

The Zadokite family of priests and their closest supporters were now forced into exile to survive.10Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications. It is during this time the first original writings were made in the collection of literature we know today as The Dead Sea Scrolls.11The Leon Levy Dead Sea Scrolls Digital Library. Israel Antiques Authority. https://www.deadseascrolls.org.il/learn-about-the-scrolls/historical-timeline This famous sprawling library of scrolls that survived in a desert cave untouched for 2,000 years contains the oldest known manuscripts of nearly every book that was later incorporated into the Hebrew Bible—as well as many that were not, including The Book of Watchers, Jubilees, and several other apocalypses involving Enoch and other visitors of the heavenly realms.12Vermes, G. (2004). The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English. Penguin UK.

Most intriguingly, these scrolls also contain a trove of original religious writings. From the content of these documents—many of which are still largely intact—we get a picture of an outsider Jewish religious community living apart from society. They rail against and reject the illegitimacy of the high priesthood in Jerusalem, while they express great reverence for Zadok and the Zadokite line. In the earliest among these writings there is a palpable sense of shock and betrayal permeating the texts that seems a perfect match with newly exiled Zadokites.13Eisenman, R. (2013). Maccabees, Zadokites, Christians, and Qumran. Grave Distractions Publications.

The Maccabees Revolt

The new non-Zadokite high priest Menelaus continued to loot sacred objects from the Temple treasury to make bribes and enrich himself, angering the populace. In the meantime, Onias III’s brother Jason had never given up his claim to the high priesthood, and was able to stage a brief coup against Menelaus, driving him from the Temple to a nearby fortress. From there Menelaus wrote of the situation to the Seleucid emperor who at that time was leading his army in an invasion of the Ptolemaic Egyptian kingdom. Convinced by Menelaus’s words that all of Judah was in revolt, he pivoted his forces to attack the Judahite people. Thousands of men, women, and children were slaughtered, and thousands of others sold into slavery. Menelaus then celebrated his restoration to the high priesthood by—in a major violation of Jewish law—inviting Antiochus inside the heart of the Temple where he helped himself to a massive amount of silver from the Treasury.14Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

The situation degraded rapidly from there. The emperor installed Greek administrators to take control of the government of Judah. Those who had supported Jason’s insurgency had their land and property seized. And because Antiochus IV considered the coup to have been religiously motivated, he began to actively suppress traditional Jewish religious practices, outlawing Jewish dietary laws, circumcision, and observation of the Sabbath. He ordered the Temple of Jerusalem rededicated to Zeus, and had the flesh of pigs offered on its holy altar. Jews who resisted the emperor’s new policies were forced to eat pork or face execution.15Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

In the rural town of Modein, a zealous priest named Mattathias defiantly refused when a Seleucid official attempted to force his community to sacrifice to Greek gods at the town’s altar. Then when another Jew stepped forward to comply, Mattathias took out a knife and stabbed his countryman to death on the altar, and then killed the government official as well. A revolt had begun.16Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

Matthatias was old and died soon after, but his son Judas—nicknamed Maccabee (“The Hammer”)—and his brothers gathered supporters and retreated into the wilderness caves of Judah, using raids, ambushes, other guerilla tactics, and steady recruitment to hold their own against the far larger and well trained Seleucid forces.17Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

The exiled Zadokites likely allied themselves with the Maccabees (Judas’s nickname was quickly adopted as a shared family name) as both groups shared an overlapping set of enemies, goals, and militantly zealous theology. Both groups are also described as retreating to the wilderness caves of Judah for a time, and adopting a limited vegetarian diet as a measure to maintain the highest levels of religious purity in imitation of an ancient Jewish sect known as the Rechabites who were described in reverent terms by the prophet Jeremiah.18Eisenman, R. (2013). Maccabees, Zadokites, Christians, and Qumran. Grave Distractions Publications.

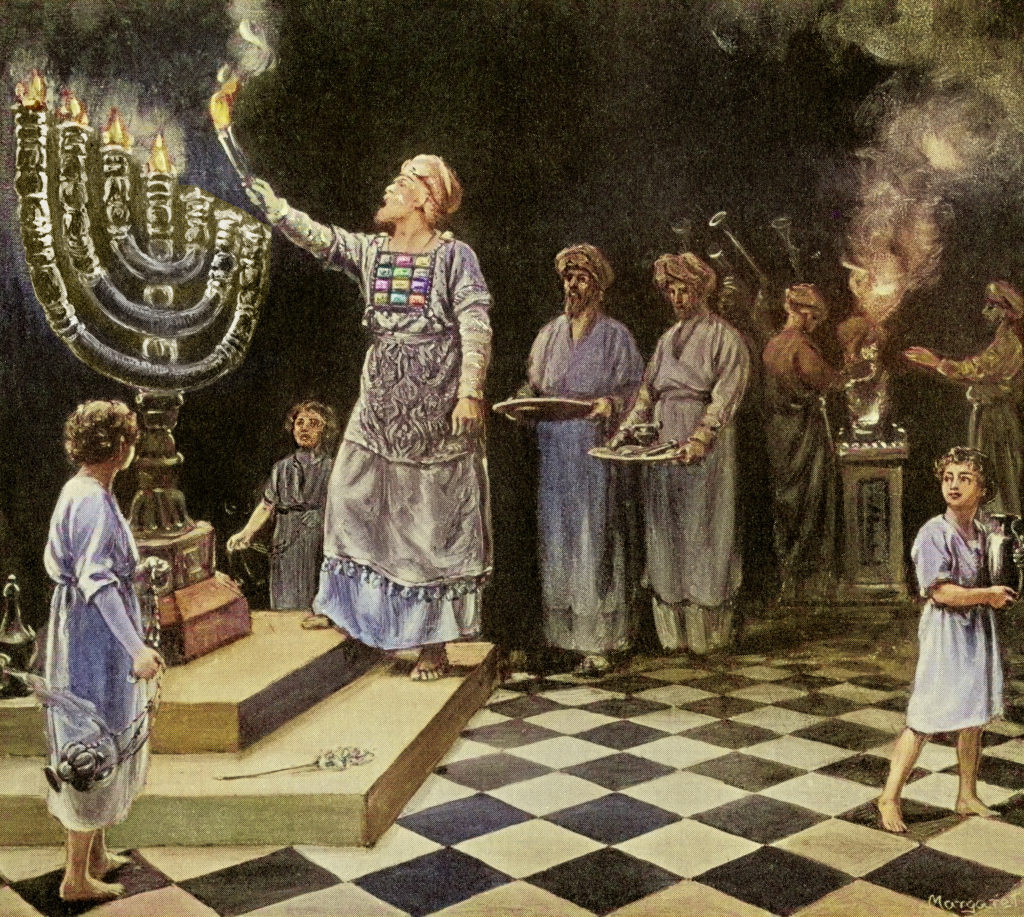

Despite hard-won successes, the Maccabees and their supporters surely would have been crushed if it weren’t for the fact that the majority of the Seleucid army was occupied by defending the empire from the invading Parthians—a resurgent form of the Persian empire—on their eastern border. Emperor Antiochus IV himself was killed while leading his army against these invaders. Judas Maccabee took advantage of the chaos surrounding the emperor’s sudden death—and struggles among his would-be successors—in order to retake control of Jerusalem. He immediately cleansed the Temple of all pagan idolatry and reinstated the daily sacrifices to Yahweh—an act commemorated to this day in the festival of Hanukkah.19Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

War would continue between the Seleucids and the Maccabees for several more years. During this period, at one pitched battle, Judas’s brother Eleazar saw that his fellow Jews were cowering in fear at the dozens of towering Seleucid war elephants. Hoping to inspire his troops and prove these behemoths were not as invulnerable as they appear, Eleazar mounted his horse and charged alone at the enemy’s front lines. If he was hoping for a miracle, it did not come, and he was trampled to death.20Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

Hoping for military aid or an alliance that could decisively change the course of the war, Judas now reached out to representatives from the powerful and expanding Roman Republic—whose widespread territories at this time stretched from Spain in the west to Northern Greece in the east. Though friendly relations were successfully established, no pact or guarantee of protection from the Seleucids could be secured.21Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

Then in 160 BCE, Judas himself was killed in battle in which his army was severely outnumbered. Rather than being a major blow to morale endangering the rebellion, the Jewish forces seemed to have their resolve hardened by the death in combat of their heroic leader. From this point forward, his surviving brothers Jonathan, Simon, and John continued to lead the revolt, carrying out a series of guerrilla attacks on the Seleucids while continuing their brother’s policy of terrorizing their fellow Jewish countrymen who were deemed insufficiently anti-Greek.22Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

Apocalypses Now

It is during these years of upheaval and strife that the apocalyptic mindset became significantly more pronounced in Jewish writings, some clearly building off the narrative and theology first committed to writing in The Book of Watchers. Further sets of revelations were attributed to Enoch in which he is given a vision of all history from Adam and Eve to the coming of the Messiah at the end of history. A book known as Jubilees retold many stories found in Genesis with key elements shared by the Enoch literature—angelology, fallen angels, giants, a future messiah, the End Time, the Last Judgment, and the post-judgment transformation of Earth into a paradise.23VanderKam, J.C. (2000). “The Book of Jubilees”. In L. H. Schiffman; J. C. VanderKam (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Vol. I. Oxford University Press.

Most famously the book of Daniel—the only full-fledged apocalyptic text to later be incorporated into the Hebrew Bible—was written at this time, describing the events of the Maccabean revolt as if predicted by a prophet who lived 400 years earlier, and introducing a figure known as the Son of Man as a glorious heavenly being who will fulfill the role of avenging messiah at the rapidly approaching end of the age.24Collins, J. J. (1984). Daniel: With an Introduction to Apocalyptic Literature. Eerdmans.

Continue Reading:

Footnotes

- 1Heckel, W. (2008). Alexander the Great: A New History. Wiley.

- 2McCarty, Nick (2004). Alexander the Great. Camberwell, Victoria: Penguin.

- 3Green, Peter (2007). Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Age. London: Phoenix.

- 4Bartlett, J. R. (2011). Between Alexander and Antiochus: Jews and Judaeans in the Hellenistic Period. Eisenbrauns.

- 5Charles River Editors. (2019). The Seleucid Empire: The History of the Empire Forged in the Ancient Near East After Alexander the Great’s Conquest. Independently published.

- 6Coogan, M. A. (2002). Between Alexandria and Antioch: Jews and Judaism in the Hellenistic Period. Oxford University Press.

- 7Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

- 8Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

- 9Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

- 10Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

- 11The Leon Levy Dead Sea Scrolls Digital Library. Israel Antiques Authority. https://www.deadseascrolls.org.il/learn-about-the-scrolls/historical-timeline

- 12Vermes, G. (2004). The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English. Penguin UK.

- 13Eisenman, R. (2013). Maccabees, Zadokites, Christians, and Qumran. Grave Distractions Publications.

- 14Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

- 15Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

- 16Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

- 17Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

- 18Eisenman, R. (2013). Maccabees, Zadokites, Christians, and Qumran. Grave Distractions Publications.

- 19Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

- 20Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

- 21Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

- 22Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

- 23VanderKam, J.C. (2000). “The Book of Jubilees”. In L. H. Schiffman; J. C. VanderKam (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Vol. I. Oxford University Press.

- 24Collins, J. J. (1984). Daniel: With an Introduction to Apocalyptic Literature. Eerdmans.