Chapter 18

Ignatius and Marcion

Ignatius of Antioch

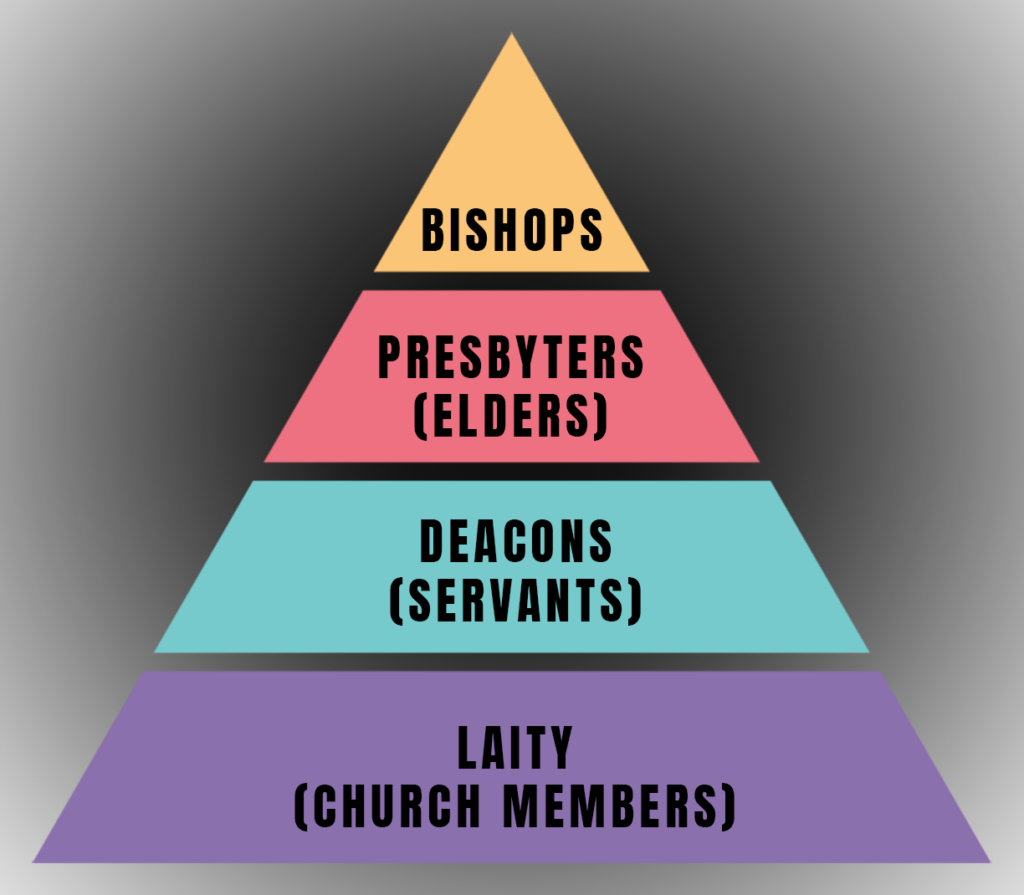

Scholars who assume that Christianity began with a historical Jesus of Nazareth and his band of fishermen followers and other lower class disciples have a difficult time explaining how it is that the church, from its very earliest origin, seems to have an established and relatively uniform structure from region to region—each community having its own bishop, elders, deacons, etc. But when it is seen that the earliest Christian communities sprung from the sect of Essene Jews which had existed in highly regimented communities for over 200 years, and is known to have had bishops overseeing each community, this mystery evaporates.

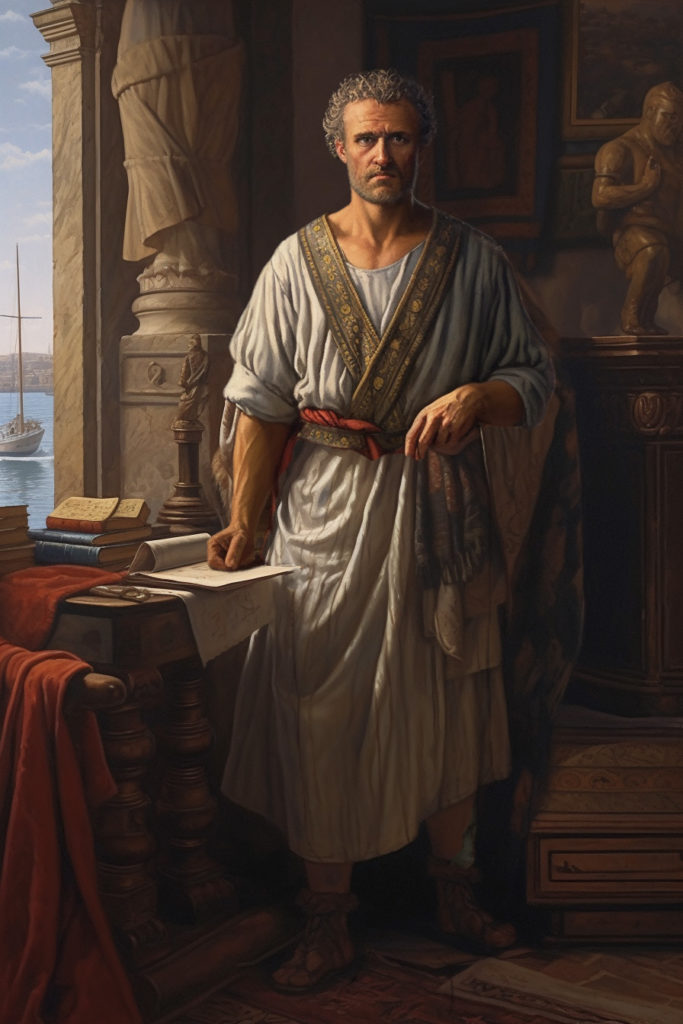

In the first decade of the 100s CE, the bishop of Antioch in Syria was a man named Ignatius. More than a dozen epistles bearing his name have survived, though only seven of them are considered authentic.1Carrier, R. On the Historicity of Christ. (2014). Sheffield Phoenix Press Ltd. Ignatius’s beliefs were aligned with those of the church in Rome which was growing in numbers and influence. In particular he champions the cause for the unquestioned authority of bishops like himself. “We are clearly obliged to look upon the bishop as the Lord himself,”2Lightfoot & Hammer. (1891). Epistle of Ignatius to the Ephesians. Early Christian Writings. https://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/ignatius-ephesians-lightfoot.html he writes, elsewhere adding: “Wherever the bishop appears, there let the people be—as wherever Jesus Christ is, there is the Catholic Church. It is not lawful to baptize or give communion without the consent of the bishop. On the other hand, whatever has his approval is pleasing to God.”3Hoole, C.H. (1885). Epistle of Ignatius to the Smyrnaeans. Early Christian Writings. https://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/ignatius-smyrnaeans-hoole.html This latter quote is also notable for being the first known use of the term Catholic (“universal”) Church,4Lightfoot, J.B. (1889). The Apostolic Fathers: Revised Texts with Introductions, Notes, Dissertations and Translations. S. Ignatius, S. Polycarp. an audacious descriptor that would later officially be adopted by the church in Rome. He is also the first known author to use the term Christianity.5Elwell, W. & Comfort, P.W. (2001). Tyndale Bible Dictionary. Tyndale House Publishers. But the letters written by Ignatius are notable for two other reasons worth examining.

Based on his letters to various churches, Ignatius lived at a time when the gospels were starting to become widespread and were convincing some Christians that Jesus had been a real historical figure, but many churches still clung to the teachings of the earliest Christians like James, Peter, and Paul, and believed only in a heavenly Lord Christ who was yet to ever come to Earth. Ignatius himself is in the former camp, and in his epistles to various churches, he argues adamantly for all Christians to believe as he does, and to shut their ears to anyone who preaches to them, “but does not speak of Jesus Christ descended from David; who was of Mary; who was actually born, and ate, and drank; and who was actually persecuted under Pontius Pilate; and was actually crucified and died—as witnessed by those in heaven, on Earth, and under the earth—and actually raised from the dead.” In another letter, Ignatius argues that true Christians are “fully convinced when it comes to our Lord that he was actually born of a virgin and baptized by John.”6Carrier, R. On the Historicity of Christ. (2014). Sheffield Phoenix Press Ltd.

Though clearly Ignatius believes in the historicity of several elements of the gospel stories as we know them, his letters also reveal his apparent use of another gospel of which we have no known surviving parallels. Unfortunately for us, he quotes this mystery gospel only sparingly. “The virginity of Mary was hidden from the Prince of this World,” he writes—referring to Satan using the same terms Paul did in his letters. Also hidden from him were “her child and the death of the Lord”. This unknown gospel, rather than provide a familiar story of Jesus’s life on Earth, instead says that the Lord was revealed to the world in the form of a brilliant star that struck people with astonishment. And at its appearance, every kind of magic, every bond of wickedness, and all ignorance was removed “when God appeared in human form for the renewal of eternal life.”7Carrier, R. On the Historicity of Christ. (2014). Sheffield Phoenix Press Ltd.

In 110 CE, Ignatius was arrested by Roman authorities. Though the charges are not stated in his letters, his crime was almost certainly simply that of being an unrepentant Christian. Though histories written by later Christian authors often exaggerated and sensationalized Roman persecutions targeting Christians during this era, most scholars find little evidence for widespread violent oppression.8Moss, C. (2013). The Myth of Persecution: How Early Christians Invented a Story of Martyrdom. This matter is clarified in a surviving exchange of letters between the Roman Emperor Trajan and his close friend—and governor of Bythinia in Asia Minor—Pliny the Younger (whose namesake uncle had perished while investigating the eruption of Mount Vesuvius).

Pliny seeks the emperor’s advice on dozens of issues including what to do about Christians in his province. He has noticed of late that this “wretched superstition” has spread from cities and towns and is now “infecting” men and women of every age and social class even in villages and farms. The emperor urges a cautious approach, specifying that such people should not be hunted down or arrested en masse. Only when a Christian comes before him and refuses to swear an oath of loyalty to Rome and its traditional gods should such a person be executed—or sent to Rome for trial if they are a citizen.9Carrier, R. On the Historicity of Christ. (2014). Sheffield Phoenix Press Ltd.

Though it may sound like it, Christians are not being singled out here. The Roman Empire had long had laws outlawing “political societies” who did not have charters from the Senate or provincial governors, and this applied to countless cults, guilds, and other societies without official recognition. Even so, Roman policy was designed to show leniency, allowing the accused to recant their allegiance and pledge loyalty to the state. It is only those who staunchly refused to do so who were deemed criminals worthy of death.10Moss, C. (2013). The Myth of Persecution: How Early Christians Invented a Story of Martyrdom.

After his arrest, Ignatius was taken under Roman guard across a land route from Antioch to Rome to face execution as a convicted criminal. His enduring popularity within the church through the Middle Ages and beyond is the result of Ignatius being the first known Christian to champion the cause of martyrdom in writing. The celebration of giving one’s life for the sake of one’s faith is something we had first seen in the books of Maccabees—particularly in the scene depicting a mother who encourages each of her seven sons to submit prayerfully and proudly to horrifying torture and death rather than blaspheme their god, for resurrection to glory awaited them. We later saw that the Essene fighters in the war with Rome were renowned for their willingness to accept death rather than call anyone their master other than God, even laughing at their tormentors.

This same spirit is carried on by Ignatius, facing a gruesome death in the arena. Writing to a local church as he made his journey to the capital of the empire, he begs them not to attempt any intervention on his behalf, for he says he is greatly looking forward to his fate. “Allow me to be bread for the wild beasts,” he writes, “for through them I am able to attain to God…Coax the wild beasts, that they may become a tomb for me and leave no part of my body behind…I will coax them to devour me quickly…even if they don’t want to do so willingly, I will force them to…Being mauled and torn apart, the scattering of bones, the mangling of limbs, the grinding of the whole body, the evil torments of the devil—let them come upon me, only that I may attain to Jesus Christ.”11Lightfoot & Hammer. (1891). Epistle of Ignatius to the Romans. Early Christian Writings. https://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/ignatius-romans-lightfoot.html

Marcionite Christianity

Around the year 100 CE in the city of Sinope along the Black Sea on the northern coast of Asia Minor—a local Christian bishop had a son named Marcion who would go on to lead one of the most popular and influential branches of Christianity of his time, and have a lasting impression on the religion as we know it today.12Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford: Oxford University Press. The area where he was raised lay just to the northeast of many of the communities founded by—or at least visited by—the apostle Paul. The revered apostle’s various letters had long been collected, copied, shared, and cherished by many regional churches. Under Marcion’s influence, Paul’s contentious break with the movement’s founders, James and Peter—over the issue of circumcision and the necessity of converts following the Law of Moses—would now become amplified and taken to an extreme.

Little is known of Marcion’s youth, but in his adulthood he is said to have grown wealthy from international trade with his own fleet of ships. He then seems to have had a religious epiphany that changed the course of his life forever.13Harnack, A. (1921). Marcion: The Gospel of the Alien God. Translated by Steely, J.E. & Bierma, L.D. Grand Rapids: Baker. For Marcion, the supremacy of Paul over all other apostles was complete, for he believed it obvious that his Jewish disciples had entirely failed to understand who he truly was—and even which god it was who had sent him into the world.14Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

In his comparative reading of the Hebrew scriptures, the letters of Paul, and the second gospel—which seems to have been the preferred gospel where he was raised—one observation struck Marcion again and again: The god of the Hebrew scriptures (Yahweh) seemed entirely incompatible with the god preached by the gospel and by Paul. Before long, he formed his signature belief that they were not, in fact, one and the same god at all. The apostle, he realized, had been preaching a higher-level god that the world had never known before Paul revealed his existence.15Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

The Jews, on the other hand, had been hoodwinked in ancient times into worshiping a lower form of god who knew nothing of compassion or love, only pitiless justice and vengeful wrath. A close reading of Paul’s letters does lend some support of this view. The apostle writes of the “god of this world” who has “blinded the minds of the unbelievers to keep them from seeing the light of the gospel of Christ.” Most assume this to be a reference to Satan, but if so, it’s easy to read Paul as equating Satan with the god of the Jews. It is this lower god, posited Marcion, who gave Moses the Law, which Paul once referred to as a “ministry of death carved into stone.”16Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

These ideas all became part of Marcion’s only known original writing, which he called The Antithesis (“contradictions”), which laid out his case by juxtaposing many of the words and actions of the god of the Hebrew scriptures alongside incompatible words and actions of Jesus as the ambassador of the secret higher god in the second gospel and the teachings of Paul.

In late 139 CE, Marcion made a very large donation to the church in Rome, and traveled there to share his views. But he found the community there to be too attached to the Hebrew scriptures, and unwilling to entertain the notion of two gods, one higher and one lower. For his troubles, he was excommunicated, and given back his donation. Undeterred, Marcion returned to Sinope and would use that city as a base for a long and dramatically successful evangelical campaign which established churches across Asia Minor and beyond, helped along by his connections in international trade and an army of inspired evangelists. Even one of his detractors admitted that his views were successfully disseminated to “many people of every nation”.17Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Though Marcion accepted what we might call the Gospel 2.0 as historical, he also believed that Jesus was a purely divine being and only ever took on the appearance of a human during his time on earth. This is a view that would soon catch hold among the so-called Gnostic Christians and other sects, standing in firm contradiction to what was being taught in churches like that of Rome.18Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Perhaps his most enduring contribution to the history of Christianity, however, is that Marcion was the first person to have created a specifically Christian canon of scriptures—in essence, he was the first to form a “New Testament”. To the Gospel 2.0 were added 10 epistles written by Paul. And that was all: one gospel, one apostle.19Beduhn, J. (2013). The First New Testament: Marcion’s Scriptural Canon. Polebridge Press. The notion of putting favored selected writings into a sacred collection—while shutting others out—had obvious advantages for churches wishing to exert control and bring unity to the increasingly wide-ranging texts used in their affiliated churches across the empire. Marcion’s actions are almost certainly what led to the Roman church eventually establishing a canon of its own—inclusive of the Hebrew scriptures.20Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford: Oxford University Press. It may have also prompted the Rabbinic Jews to decide on their own closed collection, keeping the books of the Hebrew Bible we know today while snubbing the books of Enoch, Jubilees, 1 and 2 Maccabees, and others deemed too conducive to rebellion against Rome.

Although we know Marcion to have penned at least one writing of his own, it is notable that—unlike the many early Christians—Marcion did not indulge in adding to, subtracting from, or otherwise editing the scriptures he inherited, even when doing so would have made them better fit his particular theological beliefs. As a result, he ended up with the occasional verse or story from his scriptures that seemed to deny his own beliefs. We don’t have enough surviving information to know how Marcion addressed such issues, if at all, but such nitpicks did not slow down the popularity of his branch of Christianity which may even have been the most popular of its day, and was still treated as a significant threat to the Roman Church through the 400s CE.21Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

The Second Jewish-Roman War

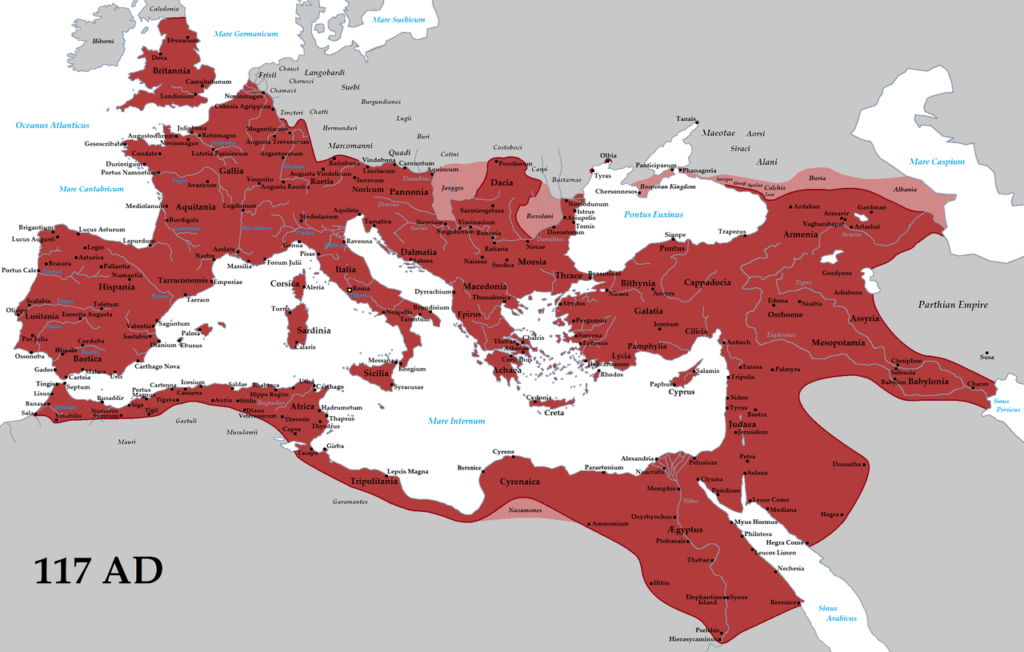

During the 110s CE, the Roman Empire reached the zenith of its territorial extent, pushing its control of Britain to the borders of Scotland, and at long last mounting a successful invasion of the Parthian Empire to the east, conquering their capital city, and gaining dominion over the lands of Mesopotamia as far west as the Persian Gulf.22Speller, E. (2004). Following Hadrian: A Second-Century Journey Through the Roman Empire. Oxford University Press.

But with a majority of Emperor Trajan’s legions engaged in his massive campaign against Parthia, a Jewish man named Lukuas from the province of Cyrenaica on the north coast of Africa, rose up as a liberator and messiah figure and incited his fellow Jews to revolt. After destroying a series of local pagan temples and attacking their worshippers, Lukuas’s forces defeated a Greek contingent in battle, forcing the survivors to flee to Alexandria in Egypt. There they sought their vengeance on the Jewish population of the city, killing and capturing many. This had the predictable effect of pushing the Alexandrian Jews to join Lukuas’s revolt as well, and the rebellious Jews ravaged the city and countryside, destroying several pagan temples as well as the tomb of Pompey—who had originally conquered Jerusalem for the Romans.23Lukuas. (2020). Livius.org. https://www.livius.org/articles/religion/messiah/messianic-claimant-17-lukuas/

News of these actions prompted Jews in northern Mesopotamia to join the revolt, launching attacks on the recently-victorious Roman legions as they marched homeward from the war with Parthia. Meanwhile on the island of Cyprus, the large Jewish population there, led by a man named Artemion, rose against the local Roman government as well, and thousands were killed in the resulting strife.24Dio, C. Roman History, Vol. V. In the homeland of Judah itself, two Jewish men named Julianus and Pappos took control of the city of Lydda, where they welcomed Lukuas when he fled Egypt.25Lukuas. (2020). Livius.org. https://www.livius.org/articles/religion/messiah/messianic-claimant-17-lukuas/

Trajan responded to the uprisings, dispatching Marcius Turbo with land and naval forces to destroy the rebel forces in Cyrene, Egypt, and then Judah—where he captured and executed Julianus and Pappos. Another general named Lucius Quietus was sent to Mesopotamia and became notorious for his cruelty in wiping out whole populations of Jews there and in neighboring Syria. Order was restored on Cyprus, and all Jews were thereafter banished from the island on pain of death. The fate of the would-be messiah Lukuas is unknown.26Collins, J.J. & Harlow, D.C. (2010). The Eerdmans Dictionary of Early Judaism. William B Eerdmans Publishing.

Unfortunately we have very little surviving information about this second war between Rome and the Jews. No equivalent figure to Flavius Josephus took part or witnessed the revolt and then wrote up their account for the ages—at least not one that survives. But if nothing else, what stands out is that the Jewish hope for an imminent messiah who would usher in the End Times had not faded even with the destruction of Jerusalem and its great temple of Yahweh, and despite the efforts of accommodationist rabbinic leaders in reshaping Judaism so as to discourage messianic revolutionary zeal.

During the campaign in Parthia, Emperor Trajan had suffered heat stroke, and as he returned home with his troops, he fell ill and died not long after.27Esposito, G. (2023). The Army of the Early Roman Empire 30 BC–AD 180. Pen and Sword Military. His successor, the Emperor Hadrian, immediately decided that the empire could not feasibly maintain control of the lands taken by Trajan, and personally traveled to Mesopotamia for peace negotiations that returned the conquered areas to the Parthians in return for an established committment to peace between the two empires.28Schlude, J.M. (2020). Rome, Parthia, and the Politics of Peace: The Origins of War in the Ancient Middle East. Routledge.

The Third Jewish-Roman War

Emperor Hadrian was unlike his predecessors. He put an end to the empire’s constant struggle to expand its territorial conquests, famously having a wall built between Roman Britain and the “barbarians” to the north.29Hodgson, N. (2017). Hadrian’s Wall: Archaeology and history at the limit of Rome’s empire. Ramsbury: Crowood Press. A devoted lover of Greek culture, he attempted to instill its virtues on all “civilized” peoples within the empire’s borders, spending more than half of his reign traveling outside of Italy—throughout all reaches of Roman dominion.30Veyne, P. (1976). Le Pain et le Cirque. Paris: Seuil. This included visits to Cyrene and Alexandria to restore public buildings destroyed during the recent Jewish revolt, including Pompey’s grave, where he hailed the general as a great hero.31Birley, A.R. (2013). Hadrian: The Restless Emperor. Routledge.

Years earlier during his trip to negotiate with the Parthians, Hadrian had met a beautiful teenage boy of humble birth named Antinous who became the emperor’s constant companion on his travels over the next several years.32Birley, A.R. (2013). Hadrian: The Restless Emperor. Routledge. In 130 CE, however, on a trip down the Nile in Egypt together with his imperial entourage, Antinous drowned in the river.33Hadrian. Historia Augusta. Devastated by the loss of his beloved partner, the emperor had him deified and had a city built in his honor there in Egypt.34Foertmeyer, V.A. (1989). Tourism in Graeco-Roman Egypt. Princeton.

Hadrian then visited Judah and surveyed the city of Jerusalem, still utterly in ruins. He announced plans to rebuild the city and temple, causing excitement and anticipation among many Jews. But their hopes were soon dashed and gave way to anger and rage when it was revealed that the city would be reconstructed as a Roman city celebrating Greek culture, including the construction of a new Temple of Jupiter where once the Temple of Yahweh had stood.35Cassius Dio. Roman History. Book 69.

Groundbreaking ceremonies for this city called Aelia Capitolina (“Aelia” being a family name of Hadrian, and “Capitolina” a reference to the Roman head god Jupiter) seem to have been the flashpoint igniting a third massive revolt of the Jews against the Roman Empire.36Cassius Dio. Roman History. Book 69. The rebel forces organized in Modi’in, the home city of the Maccabees, and spread from there.37Axelrod, A. (2009). Little-Known Wars of Great and Lasting Impact. Fair Winds Press. They were led by the military commander Simon Bar-Koseva and spiritual leader Rabbi Akiva who openly proclaimed Bar-Koseva to be the long-awaited messiah who would save the Jews and lead them to victory over all enemies in an End Times battle. It was Akiva who, during the revolt, bestowed this leader with the altered last name Bar-Kokhba meaning “Son of the Star”. This was a reference to the same scriptural quote from the book of Numbers (“There shall come a star out of Jacob, a scepter shall rise out of Israel”) whose messianic interpretation was said by Flavius Josephus to have been the driving force behind the First Jewish-Roman war.38Mor, M. (2016). The Second Jewish Revolt: The Bar Kokhba War, 132-136 CE. Brill.

Having learned from various mistakes of the first revolt 60 years prior, the Jewish rebels, numbering many tens of thousands, had initial successes crushing the Roman forces stationed in Judah, and nearly gained control of Jerusalem. But the near-infinite ability of the empire to supply reinforcements in overwhelming numbers put the rebels on the run for much of the two-and-a-half year war. Bar-Kokhba’s forces used the desert caves of the highlands south of Jerusalem as a base of operations late in the conflict, and several letters written by the rebel leader himself have been discovered there in modern times.39Cassius Dio. Roman History. Book 69. This location—not far from the caves in which the Dead Sea Scrolls were found, and near to the Essene settlement at Qumran—suggests there may have been a connection between these two sets of virulently anti-Roman groups. Either way, it’s abundantly clear that violent Jewish messianism had not been curbed even after two disastrous revolts against their Roman overlords over the past 6 decades, and depite the fact that the expected army of angels coming on the clouds still never materialized.

Once again, we lack a figure like Flavius Josephus to provide any sort of detailed account of the various battles and intimate details of the war. But we do know its aftermath. The Romans ruthlessly hunted down the rebels. Archeologists excavating one cave used by Bar-Kokhba’s forces nicknamed it the Cave of Horror after finding the skeletons of 40 women, children, and men.40“Learn About the Scrolls: Bar Kokhba Revolt Refuge Caves: Nahal Hever Cave 8 (8Hev)”. Israel Antiquities Authority: The Leon Levy Dead Sea Scrolls Digital Library. Ten members of the Jewish high court (Sanhedrin) were executed, and the gruesome fate of Rabbi Akiva is variously reported by later rabbinic tradition: that he was burned at the stake, that he was flayed with iron combs, or that the skin of his head was pulled off.41Singer, I.; et al., eds. (1906). “10447-martyrs-the-ten”. The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

Once Bar-Kokhba’s forces were finally defeated at the mountain fortress of Betar, the Roman army moved systematically across Judah, destroying every city and village, effectively driving all Jews from the land. The death toll is thought to rival that of the First Jewish-Roman revolt, with numbers in the hundreds of thousands.42Siebek, M.; et al. Edited by Schäfer, P. (2003). The Bar Kokhba War Reconsidered. Mohr Siebek. In addition, so many Jews were sold into slavery that the price of a slave is said to have fallen to that of a horse.43Powell, L. (2017). The Bar Kokhba War AD 132-136, Osprey Publishing.

Hadrian was dismayed at the great cost of suppressing the revolt, and took further actions intended at neutralizing Jewish nationalism forever. He prohibited any use of the Hebrew scriptures, and had their scrolls ceremonially burned at the altar when the new Temple of Jupiter was built in the new city of Aelia Capitolina—where he also installed statues of Jupiter and of himself. Jews were completely banned on pain of death from entering the city, and this ban would remain in effect for hundreds of years to come, preventing the area from being a major center of Judaism again until modern times. Even the very name of Judah was erased, with Hadrian renaming the land Palestine after the ancient enemies of the Jews, the Philistines.44Eshel, H. (2006). “4: The Bar Kochba Revolt, 132 – 135”. In T. Katz, Steven (ed.). The Cambridge History of Judaism. Vol. 4. The Late Roman-Rabbinic Period. Cambridge.

Continue Reading:

Chapter 19: The Fourth Gospel and Gnostic Christianity

Footnotes

- 1Carrier, R. On the Historicity of Christ. (2014). Sheffield Phoenix Press Ltd.

- 2Lightfoot & Hammer. (1891). Epistle of Ignatius to the Ephesians. Early Christian Writings. https://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/ignatius-ephesians-lightfoot.html

- 3Hoole, C.H. (1885). Epistle of Ignatius to the Smyrnaeans. Early Christian Writings. https://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/ignatius-smyrnaeans-hoole.html

- 4Lightfoot, J.B. (1889). The Apostolic Fathers: Revised Texts with Introductions, Notes, Dissertations and Translations. S. Ignatius, S. Polycarp.

- 5Elwell, W. & Comfort, P.W. (2001). Tyndale Bible Dictionary. Tyndale House Publishers.

- 6Carrier, R. On the Historicity of Christ. (2014). Sheffield Phoenix Press Ltd.

- 7Carrier, R. On the Historicity of Christ. (2014). Sheffield Phoenix Press Ltd.

- 8Moss, C. (2013). The Myth of Persecution: How Early Christians Invented a Story of Martyrdom.

- 9Carrier, R. On the Historicity of Christ. (2014). Sheffield Phoenix Press Ltd.

- 10Moss, C. (2013). The Myth of Persecution: How Early Christians Invented a Story of Martyrdom.

- 11Lightfoot & Hammer. (1891). Epistle of Ignatius to the Romans. Early Christian Writings. https://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/ignatius-romans-lightfoot.html

- 12Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- 13Harnack, A. (1921). Marcion: The Gospel of the Alien God. Translated by Steely, J.E. & Bierma, L.D. Grand Rapids: Baker.

- 14Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- 15Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- 16Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- 17Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- 18Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- 19Beduhn, J. (2013). The First New Testament: Marcion’s Scriptural Canon. Polebridge Press.

- 20Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- 21Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- 22Speller, E. (2004). Following Hadrian: A Second-Century Journey Through the Roman Empire. Oxford University Press.

- 23Lukuas. (2020). Livius.org. https://www.livius.org/articles/religion/messiah/messianic-claimant-17-lukuas/

- 24Dio, C. Roman History, Vol. V.

- 25Lukuas. (2020). Livius.org. https://www.livius.org/articles/religion/messiah/messianic-claimant-17-lukuas/

- 26Collins, J.J. & Harlow, D.C. (2010). The Eerdmans Dictionary of Early Judaism. William B Eerdmans Publishing.

- 27Esposito, G. (2023). The Army of the Early Roman Empire 30 BC–AD 180. Pen and Sword Military.

- 28Schlude, J.M. (2020). Rome, Parthia, and the Politics of Peace: The Origins of War in the Ancient Middle East. Routledge.

- 29Hodgson, N. (2017). Hadrian’s Wall: Archaeology and history at the limit of Rome’s empire. Ramsbury: Crowood Press.

- 30Veyne, P. (1976). Le Pain et le Cirque. Paris: Seuil.

- 31Birley, A.R. (2013). Hadrian: The Restless Emperor. Routledge.

- 32Birley, A.R. (2013). Hadrian: The Restless Emperor. Routledge.

- 33Hadrian. Historia Augusta.

- 34Foertmeyer, V.A. (1989). Tourism in Graeco-Roman Egypt. Princeton.

- 35Cassius Dio. Roman History. Book 69.

- 36Cassius Dio. Roman History. Book 69.

- 37Axelrod, A. (2009). Little-Known Wars of Great and Lasting Impact. Fair Winds Press.

- 38Mor, M. (2016). The Second Jewish Revolt: The Bar Kokhba War, 132-136 CE. Brill.

- 39Cassius Dio. Roman History. Book 69.

- 40“Learn About the Scrolls: Bar Kokhba Revolt Refuge Caves: Nahal Hever Cave 8 (8Hev)”. Israel Antiquities Authority: The Leon Levy Dead Sea Scrolls Digital Library.

- 41Singer, I.; et al., eds. (1906). “10447-martyrs-the-ten”. The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

- 42Siebek, M.; et al. Edited by Schäfer, P. (2003). The Bar Kokhba War Reconsidered. Mohr Siebek.

- 43Powell, L. (2017). The Bar Kokhba War AD 132-136, Osprey Publishing.

- 44Eshel, H. (2006). “4: The Bar Kochba Revolt, 132 – 135”. In T. Katz, Steven (ed.). The Cambridge History of Judaism. Vol. 4. The Late Roman-Rabbinic Period. Cambridge.