Chapter 25

Rivals to Early Christianity

All Roads Lead to Rome

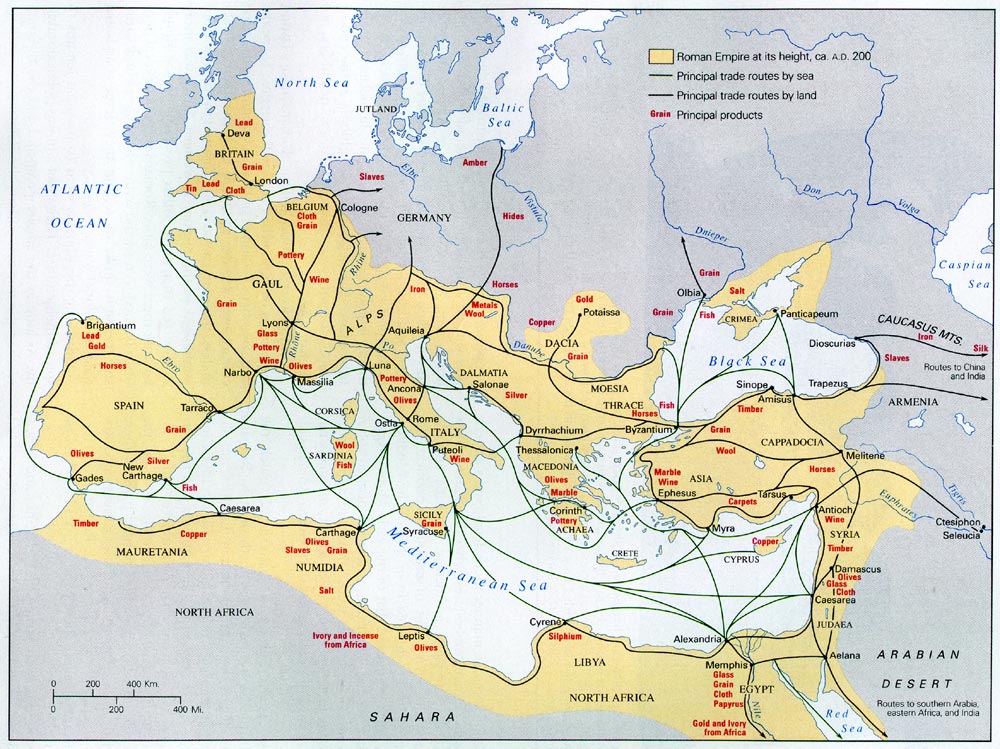

Though it was never a given that the Roman church would win out over its rivals, in retrospect it had key advantages simply by being headquartered in the empire’s capital. With its central location and myriad sea and land-based trade routes connecting it with all parts of the empire and beyond, ideas disseminating from Rome could more easily be spread. Having the largest population of any city in the world allowed it a faster growth rate as well. (Converting 1% of the 1 million inhabitants of the city of Rome to Catholicism would be far more impactful than, for example, than converting 1% of the 200,000 people living in Ephesus to Marcionite Christianity). Finally, and perhaps most importantly, Rome was the center of the vast bureaucracy that steered the ship of the state. Converting the leader of a major city like Antioch to Christianity would surely be influential, but converting the leader of Rome would forever alter history.

Not all of the Roman church’s competition was coming from other branches of Christianity or from the traditional worship of the Graeco-Roman Gods. The various other salvation religions we’ve looked at were still going strong at this time, and the faith known as Mithraism—described in Chapter 10—was gaining popularity at an impressive rate.

Had events unraveled a little differently, it is not unthinkable that this religion rather than Christianity could have gone on to become the official religion of the empire—archeologists have unearthed over 400 of the faith’s unmistakable arched-ceiling, semi-underground temples called Mithrea spanning every province of the empire from Egypt to Portugal, and Germany to Britain, as well as further east into what is today Iran.1Clauss, M. (2000). The Roman cult of Mithras : the god and his mysteries. Edinburgh University Press. One expert has estimated that, at the height of the religion, the city of Rome alone would have had “not less than 680 to 690” mitharea.2Coarelli, Filippo; Beck, Roger; Haase, Wolfgang (1984). Aufstieg und niedergang der römischen welt [The Rise and Decline of the Roman World] (in German). Walter de Gruyter.

The Decian Persecution

The Roman Empire entered the 200s CE in tattered shape after a long series of assassinated emperors, clashing internal factions, and another hugely expensive war of conquest against Parthia—immediately followed by the ceding of all newly conquered land in return for peace.3Southern, P. (2015). The Roman Empire from Severus to Constantine. Taylor & Francis.

In 203 CE, a Syrian child assigned male was born heir to the high priesthood of a popular local solar deity who shared the child’s name: Elagabulus. A decade and a half later, in 218 CE, a Roman political faction plotted against the Emperor Macrinus, and claimed that young Elagabalus had been secretly sired by a former emperor, and they hailed the 14-year-old as the new ruler of the Roman Empire.4Ball, W. (2000). Rome in the East. Routledge. Soon after this, with the coup successful, the Syrian teen was presented with Macrinus’s head.5Scott, A.G. (2018). Emperors and Usurpers: An Historical Commentary on Cassius Dio’s Roman History. Oxford University Press.

The reign of Elagabalus has been buried under centuries of slanderous reports, and it is difficult to sift truth from fiction.6Ball, W. (2000). Rome in the East. Routledge. One certainty is that the Syrian version of Ba’al was imported to Rome under the guise of Sol Invictus (“Invincible Sun”), and was made the Roman pantheon’s new chief deity, above even Jupiter.7Halsberghe, G. (2015). The Cult of Sol Invictus. Netherlands: Brill. Elagabalus is described by a contemporary Roman historian as having worn makeup, feminine wigs, and having removed all body hair. When referred to as “lord” by a member of the court, Elagabalus replied, “Do not call me ‘lord’, for I am a lady.” Elagabalus had a series of relationships with both women and men, 8Scott, A.G. (2018). Emperors and Usurpers: An Historical Commentary on Cassius Dio’s Roman History. Oxford University Press. and to the latter enjoyed being called “mistress, wife, and queen”.9Cassius Dio: Greek Intellectual and Roman Politician. (2016). Brill. She is said to have spoken in a soft, feminine voice, and offered a vast sum of money to any physician who could provide her with a vagina,10Trans Historical: Gender Plurality Before the Modern. (2021). Cornell University Press. and for all these reasons, it seems entirely fitting to refer to Elagabalus as the only known transgender empress of Rome. During her four-year reign, the Senate had its first two women participants,11Burns, J. (2006). Great Women of Imperial Rome: Mothers and Wives of the Caesars. Taylor & Francis. but this innovation was immediately undone upon her assassination at age 18.12Hay, J. S. (1911). The Amazing Emperor Heliogabalus. United Kingdom: Macmillan.

Over the following decades, the empire faced dire threats. Germanic and other northern tribes such as the Goths, Vandals, Alamanni, and Carpi were invading Roman Gaul and making raids all across the northern borders of the empire in Europe.13Southern, P. (2015). The Roman Empire from Severus to Constantine. Taylor & Francis. Meanwhile, plague swept across the provinces, killing as many as 5,000 people a day in Rome, and reducing the population of Alexandria in Egypt by more than half. Corpses lay strewn across cities and towns. The economy and food production ground to a halt, having disastrous effects on the ability of the empire to defend itself from invaders.14Harper, K. (2017). The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire. Princeton University Press.

In 249 CE, the emperor known as Philip the Arab was bested in battle and succeeded by one of his generals named Decius who hoped to return the empire to the glory days it had known during the so-called Pax Romana under leaders like his personal hero Trajan a century earlier.15The Rise of Christianity. (1984). Darton, Longman & Todd. In addition to securing the empire’s borders, building grand public baths, and restoring the Colosseum after it had been damaged by lightning strikes, he also sought to uplift public morality and piety by renovating the state religion.16Nathan, G. & McMahon, R. De Imperatoribus Romanis. Trajan Decius (249-251 A.D.) and Usurpers During His Reign. San Diego State University. https://roman-emperors.sites.luc.edu/decius.htm In 250 CE, he issued an edict requiring all inhabitants of the empire to make an offering “for the safety of the empire”, pledging their loyalty to the ancestral gods, and consuming the sacrificial food and drink before a magistrate who would then issue them a certificate of record.17The Rise of Christianity. (1984). United Kingdom: Darton, Longman & Todd. Anyone defying this order risked torture and execution,18Moss, C. (2013). The Myth of Persecution: How Early Christians Invented a Story of Martyrdom. HarperCollins. though Jews were exempt.19Graeme C. (2005). Third-Century Christianity. In The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume XII: The Crisis of Empire, edited by Alan Bowman, Averil Cameron, and Peter Garnsey. Cambridge University Press.

Though later Christians would paint a picture of heroic early martyrs defying a villainous pagan empire bent on their utter destruction,20Scarre, C. (2012). Chronicle of the Roman Emperors: The Reign-by-reign Record of the Rulers of Imperial Rome. Thames & Hudson. modern historians consider this act by Decius to represent the only empire-wide persecution up to this time for which there is convincing evidence.21Moss, C. (2013). The Myth of Persecution: How Early Christians Invented a Story of Martyrdom. United States: HarperCollins. It is unknown how many Christians abandoned their faith—or pretended to—to avoid arrest. Some are known to have made a show of defiance in choosing death over abasement—including Pope Fabius in Rome who perished in prison.22The Rise of Christianity. (1984). United Kingdom: Darton, Longman & Todd. But the Christian populations of this time were likely hit harder by the recent plague than they were by judicial executions. During the reign of the successor pope, Cornelius, there is estimated to have been 50,000 Christians living in the capital.23McBrien, R.P. (2004). National Catholic Reporter, vol. 40, General OneFile. Gale. Sacred Heart Preparatory (BAISL). A year after issuing the edict, emperor Decius was killed in battle against the Goths.24Pearson, P. N. (2022). The Roman Empire in Crisis, 248–260: When the Gods Abandoned Rome. Pen & Sword Books.

Elchasaism

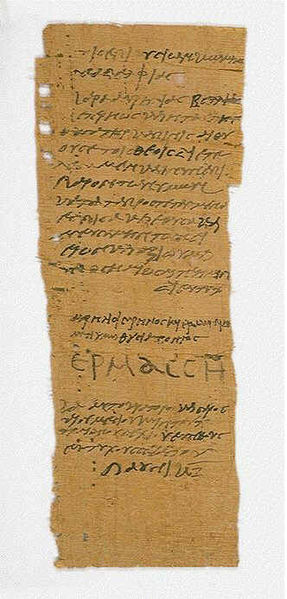

In his book The Refutation of All Heresies, Hippolytus related a story that, around the year 220 CE, a Jewish-Christian man arrived in Rome carrying a book he said he had received in Persia by a righteous man named Elchasai (“Hidden Power”). The book was said to have been revealed to Elchasai by a 96-mile tall angel, who was the Son of God—and standing beside him at the same height was his sister, the Holy Spirit. The book’s contents were described as announcing a special new second remission of sins, along with a new baptism that allows the forgiveness of even the worst manner of sins.25Hippolytus. Refutation of All Heresies, IX, 8–13

Two later church elders also wrote of a group of Christians they refer to as the Elchaisaites, describing them as utterly rejecting the apostle Paul,26Luttikhuizen, G. (2008). Elchasaites and Their Book. University of Groningen. DOI: 10.1163/9789004186866_013 and claiming to have a new book of revelation which condemns virginity and abstinence. It also apparently sanctioned making of sacrifices to idols if it is done only perfunctorily to avoid persecution or death.27Eusebius. History 6.38. “The Heresy of the Elkesites.” The unique holy book of the Elchaisites was said to be in use among various groups of Ebionites and other Jewish-Christians practicing daily baptizing rituals.28Epiphanius of Salamis. Panarion.

Manichaeism

In 216 CE, in the capital of the Parthian Empire—near what is today Baghdad in Iraq—a son was born to an Elchesaite Jewish-Christian couple who would go on to be known as Mani (“Light” or “Enlightened”).29Henning, W. B. (1943). The Book of the Giants. University of London. He later wrote that at ages 12 and 24 he received sacred visions which prompted him to leave his parents’ faith and begin a new religious movement to spread the true message of Jesus in a new gospel.30Wearring, Andrew (2008-09-19). “Manichaean Studies in the 21st Century”. Sydney Studies in Religion. https://openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/index.php/SSR/article/view/254

Exiled from his homeland for his deviant doctrines, Mani traveled to India where he studied Hinduism, Buddhism, and other related sects.31Sachau, E. C. (2013). Alberuni’s India: An Account of the Religion, Philosophy, Literature, Geography, Chronology, Astronomy, Customs, Laws and Astrology of India: Volume I. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis. He then returned home to what was now the Sassanid Persian Empire. Despite Zoroastrianism being the official religion of the empire, Mani gained an audience with its ruler Shapur, and dedicated to him a book he had written called The Text of Two Principles, which became a foundational sacred text of Manichaeism.32Sundermann, Werner (2009-07-20), “MANI”, Encyclopedia Iranica, Sundermann. https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/mani-founder-manicheism Mani presented himself as not merely a prophet, but the final prophet God would send. He described a version of history in which God had sent a series of holy men who revealed great wisdom to humankind, most notably: Krishna, Buddha, Zoroaster, Jesus, and now himself.33Exploring Religious Diversity and Covenantal Pluralism in Asia: Volume II, South & Central Asia. (n.d.). United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis. Taking the titles “apostle of Jesus Christ” and “apostle of the true God”, he further identified himself as the promised Paraclete (“Helper”, “Advocate”), who in the fourth gospel (attributed to John), Jesus told his disciples would arrive after his death.34The Cambridge History of Iran. (1968). Cambridge University Press.

While the Sassanid emperor was not converted to this nascent religious movement, he welcomed Mani as a member of his imperial court where the prophet gained a reputation for performing miracles such as healings, levitation, and teleportation. He was also a renowned painter.35Sundermann, Werner (2009-07-20), “MANI”, Encyclopedia Iranica, Sundermann. https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/mani-founder-manicheism

Mani went on to write several more works, all of which only survive in parts.36Augustine, S. (2008). The Confessions. OUP Oxford. From them, it is clear that Mani kept the extreme dualism of Zoroastrianism’s constant struggle between Light and Dark. From gnostic Christianity he incorporated the notion that Jesus had revealed the celestial nature of the soul which longed to reunite with the divine. Mani had copies of the Enoch apocalypses used by the Essenes, and quoted from them in his works, greatly informing his cosmology.37“MANICHEISM,” Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, 2014, available at http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/manicheism-parent He also made use of the gnostic Gospel of Thomas, and the Acts of Thomas,38Runciman, S. (1982). The Medieval Manichee: A Study of the Christian Dualist Heresy. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. chronicling, as we’ve seen, the apostle’s missionary journey to India.

Mani also retained from Christianity its vision of the End Times judgment in which Jesus separates the righteous from the sinners, casting the latter into Hell with the Devil.39“MANICHEISM,” Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, 2014, available at http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/manicheism-parent From Hindu culture he adopted a simplified version of a caste system in which a small number of the “Elect” would strive for salvation by living their lives by a strict ascetic code of virtue while assisted in this endeavor by the “Hearers”—the lower caste of believers who lived to assist the Elect in their journey. Borrowing the notion of the transmigration of souls from Buddhism, these Hearers attempted to live virtuously enough to be born as an Elect in their next incarnation.40Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2024, March 6). Manichaeism. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Manichaeism

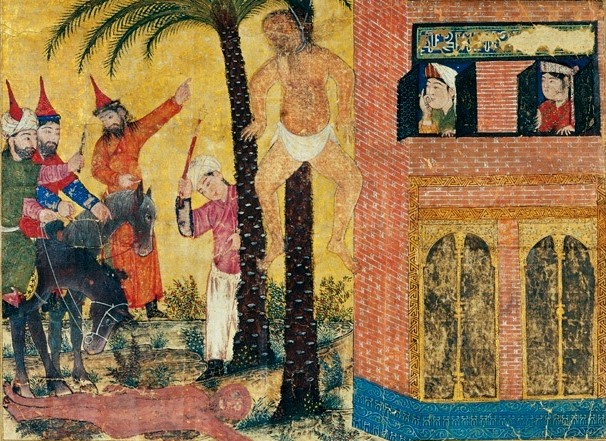

After Shapur and his successor Hormizd’s imperial support of Mani, a new emperor took the throne who considered himself a traditionalist Zoroastrian reformer, and he thus acted with great intolerance toward other religious movements of the realm. In this atmosphere, Mani was thrown in prison at age 58.41“Bahrām I,” Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, 2014, available at https://iranicaonline.org/articles/bahram-01 Accounts of his death in 274 CE vary, with some saying he was flayed and had his body hung over the city gate of the intellectual capital of the Sassanid Empire, Gundeshapur. Others present his death as a crucifixion in the style of Jesus,42Al-Biruni. The Chronology of Ancient Nations. while more probably he simply died in prison—though he may have had his head removed after death and set on display.43Sundermann, Werner (2009-07-20), “MANI”, Encyclopedia Iranica, Sundermann. https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/mani-founder-manicheism

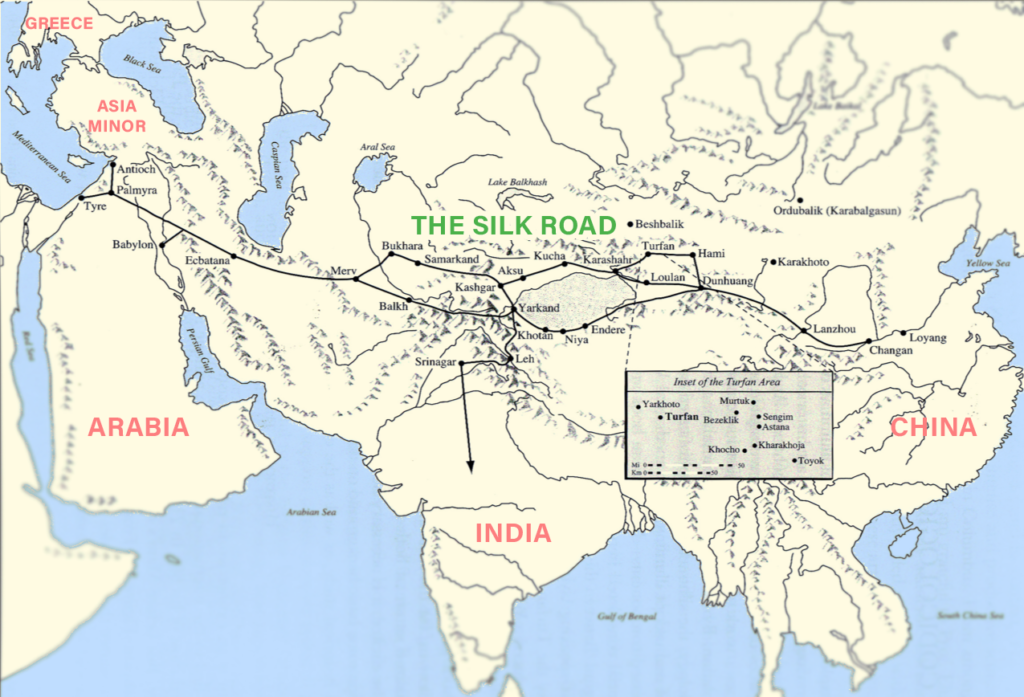

Manichaeism spread with remarkable speed through the east and west, reaching Egypt by 244 CE and Rome by 280 CE.44Lieu, S.N.C. (1985). Manichaeism in the Later Roman Empire and Medieval China: A Historical Survey. Manchester University Press. By 302 CE it faced persecution by Roman Emperor Diocletian, with its holy books targeted for destruction and anyone openly practicing the religion subject to having all their possessions confiscated, and being sent to work in the mines.45Gardner, I & Lieu, S.N.C. eds. (2004). Manichaean Texts from the Roman Empire. Cambridge University Press. Nonetheless, just ten years later there are reports of Manichaean monasteries in the capital.46Lieu, S.N.C. (1985). Manichaeism in the Later Roman Empire and Medieval China: A Historical Survey. Manchester University Press. To the east, the religion was spread along the famous Silk Road trading route, establishing itself in China by the 600s CE.47Lieu, S.N.C. (1998). Manachaeism in Central Asia and China. Brill Publishers. Though facing similar or worse persecutions in the Tang and Ming dynasties, Manichaean communities survived there until at least the 1400s CE.48Hajianfard, R. (2016). Boku Tekin and the Uyghur Conversion to Manichaeism (763). ABC-CLIO. In Africa, the hugely influential ascetic theologian Augustine of Hippo was a member of the Manichaean faith until he converted to Roman Catholicism at age 32.49Augustine and Manichaean Christianity: Selected Papers from the First South African Conference on Augustine of Hippo, University of Pretoria, 24-26 April 2012. (2013). Brill.

Continue Reading:

Chapter 26: Christianity Entrenched

Footnotes

- 1Clauss, M. (2000). The Roman cult of Mithras : the god and his mysteries. Edinburgh University Press.

- 2Coarelli, Filippo; Beck, Roger; Haase, Wolfgang (1984). Aufstieg und niedergang der römischen welt [The Rise and Decline of the Roman World] (in German). Walter de Gruyter.

- 3Southern, P. (2015). The Roman Empire from Severus to Constantine. Taylor & Francis.

- 4Ball, W. (2000). Rome in the East. Routledge.

- 5Scott, A.G. (2018). Emperors and Usurpers: An Historical Commentary on Cassius Dio’s Roman History. Oxford University Press.

- 6Ball, W. (2000). Rome in the East. Routledge.

- 7Halsberghe, G. (2015). The Cult of Sol Invictus. Netherlands: Brill.

- 8Scott, A.G. (2018). Emperors and Usurpers: An Historical Commentary on Cassius Dio’s Roman History. Oxford University Press.

- 9Cassius Dio: Greek Intellectual and Roman Politician. (2016). Brill.

- 10Trans Historical: Gender Plurality Before the Modern. (2021). Cornell University Press.

- 11Burns, J. (2006). Great Women of Imperial Rome: Mothers and Wives of the Caesars. Taylor & Francis.

- 12Hay, J. S. (1911). The Amazing Emperor Heliogabalus. United Kingdom: Macmillan.

- 13Southern, P. (2015). The Roman Empire from Severus to Constantine. Taylor & Francis.

- 14Harper, K. (2017). The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire. Princeton University Press.

- 15The Rise of Christianity. (1984). Darton, Longman & Todd.

- 16Nathan, G. & McMahon, R. De Imperatoribus Romanis. Trajan Decius (249-251 A.D.) and Usurpers During His Reign. San Diego State University. https://roman-emperors.sites.luc.edu/decius.htm

- 17The Rise of Christianity. (1984). United Kingdom: Darton, Longman & Todd.

- 18Moss, C. (2013). The Myth of Persecution: How Early Christians Invented a Story of Martyrdom. HarperCollins.

- 19Graeme C. (2005). Third-Century Christianity. In The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume XII: The Crisis of Empire, edited by Alan Bowman, Averil Cameron, and Peter Garnsey. Cambridge University Press.

- 20Scarre, C. (2012). Chronicle of the Roman Emperors: The Reign-by-reign Record of the Rulers of Imperial Rome. Thames & Hudson.

- 21Moss, C. (2013). The Myth of Persecution: How Early Christians Invented a Story of Martyrdom. United States: HarperCollins.

- 22The Rise of Christianity. (1984). United Kingdom: Darton, Longman & Todd.

- 23McBrien, R.P. (2004). National Catholic Reporter, vol. 40, General OneFile. Gale. Sacred Heart Preparatory (BAISL).

- 24Pearson, P. N. (2022). The Roman Empire in Crisis, 248–260: When the Gods Abandoned Rome. Pen & Sword Books.

- 25Hippolytus. Refutation of All Heresies, IX, 8–13

- 26Luttikhuizen, G. (2008). Elchasaites and Their Book. University of Groningen. DOI: 10.1163/9789004186866_013

- 27Eusebius. History 6.38. “The Heresy of the Elkesites.”

- 28Epiphanius of Salamis. Panarion.

- 29Henning, W. B. (1943). The Book of the Giants. University of London.

- 30Wearring, Andrew (2008-09-19). “Manichaean Studies in the 21st Century”. Sydney Studies in Religion. https://openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/index.php/SSR/article/view/254

- 31Sachau, E. C. (2013). Alberuni’s India: An Account of the Religion, Philosophy, Literature, Geography, Chronology, Astronomy, Customs, Laws and Astrology of India: Volume I. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis.

- 32Sundermann, Werner (2009-07-20), “MANI”, Encyclopedia Iranica, Sundermann. https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/mani-founder-manicheism

- 33Exploring Religious Diversity and Covenantal Pluralism in Asia: Volume II, South & Central Asia. (n.d.). United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis.

- 34The Cambridge History of Iran. (1968). Cambridge University Press.

- 35Sundermann, Werner (2009-07-20), “MANI”, Encyclopedia Iranica, Sundermann. https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/mani-founder-manicheism

- 36Augustine, S. (2008). The Confessions. OUP Oxford.

- 37“MANICHEISM,” Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, 2014, available at http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/manicheism-parent

- 38Runciman, S. (1982). The Medieval Manichee: A Study of the Christian Dualist Heresy. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

- 39“MANICHEISM,” Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, 2014, available at http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/manicheism-parent

- 40Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2024, March 6). Manichaeism. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Manichaeism

- 41“Bahrām I,” Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, 2014, available at https://iranicaonline.org/articles/bahram-01

- 42Al-Biruni. The Chronology of Ancient Nations.

- 43Sundermann, Werner (2009-07-20), “MANI”, Encyclopedia Iranica, Sundermann. https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/mani-founder-manicheism

- 44Lieu, S.N.C. (1985). Manichaeism in the Later Roman Empire and Medieval China: A Historical Survey. Manchester University Press.

- 45Gardner, I & Lieu, S.N.C. eds. (2004). Manichaean Texts from the Roman Empire. Cambridge University Press.

- 46Lieu, S.N.C. (1985). Manichaeism in the Later Roman Empire and Medieval China: A Historical Survey. Manchester University Press.

- 47Lieu, S.N.C. (1998). Manachaeism in Central Asia and China. Brill Publishers.

- 48Hajianfard, R. (2016). Boku Tekin and the Uyghur Conversion to Manichaeism (763). ABC-CLIO.

- 49Augustine and Manichaean Christianity: Selected Papers from the First South African Conference on Augustine of Hippo, University of Pretoria, 24-26 April 2012. (2013). Brill.