Chapter 14

Vespasian and Josephus

Triumph and the Fate of Jerusalem

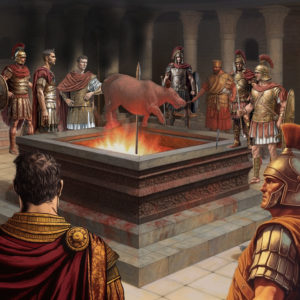

As the few survivors of the Temple siege fled, and the House of God burned to the ground, the Roman soldiers brought their beloved military ensigns (long poles, each with a golden eagle on top, treated with utmost reverence) into the Temple ruins and worshiped them there with accompanying sacrifices. A number of priests who had successfully hidden during the assault were now driven by starvation to reveal themselves. Titus had them all executed.1Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

He then ordered his troops to go house-to-house all throughout the main part of the city. They were to kill every adult male they came across, and anyone old and infirm. Women and young children were taken alive to be sold into slavery. He ordered them to plunder all the buildings and houses, and then burn them down along with any survivors hiding inside. The soldiers were happy to see the city destroyed. After an enormous number of Jews had been slaughtered in this way, Titus altered his orders. He had his men collect the tallest and most intimidating-looking rebel fighters they could find and set them aside to be paraded through Rome in a triumphal parade. The remaining adult men were to be taken captive in chains and sent to work in the mines in Egypt, while those under 17 years of age were to be sold into slavery. Since the Romans did not have enough food supplies to feed all the starving Jewish prisoners, a great many of them died in their chains.2Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

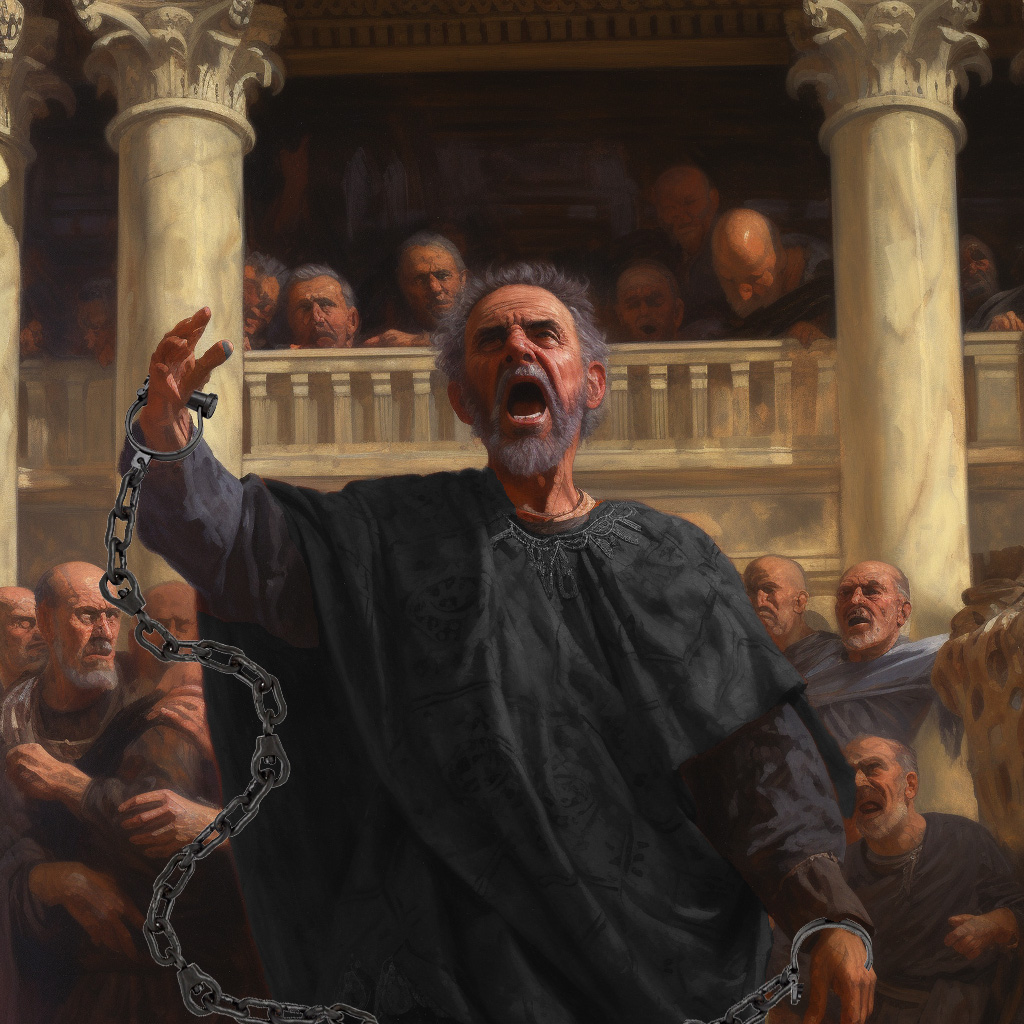

The rebel leader Simon Bar-Giora managed to escape the destruction of the Temple by entering a secret tunnel with his most trusted followers. They had limited provisions, there was no way out except the way they had come in, and a garrison of Roman troops still occupied the area. Perhaps making one last attempt at provoking divine intervention as a messiah, Simon dressed himself in a white robe with a purple cloak and arose from the ground where the Temple had stood. The Romans were astonished at first, uncertain what to do. They summoned their captain who managed to get Simon to identify himself and he was then put in chains along with those with him. John of Gischala had been captured in the fighting as well.

When all three sets of city walls were now demolished, the city was burned to the ground. 484 years after the Babylonians had reduced the holy city to ashes, the Romans now did the same. Virtually nothing remained standing to show that a grand city had once occupied the spot.3Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

Joseph Ben-Matityahu had been hated by the Roman soldiers almost as much as he was hated by his fellow Jews. Anytime the legions suffered a setback or defeat, they accused him of treachery since he had already proven himself a traitor. They several times asked Vespasian and Titus to execute him, but both father and son would not listen. Now—in the aftermath of the destruction of the holy city and 200,000 Jews killed—Titus offered Ben-Matityahu not just his own freedom, but the freedom of 190 members of his family and friends who had been taken prisoner, with all of their possessions restored to them. Three of his friends were being crucified when Ben-Matityahu spotted them and asked for them to be taken down. Two died from their wounds, but the other survived after receiving medical care.4Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

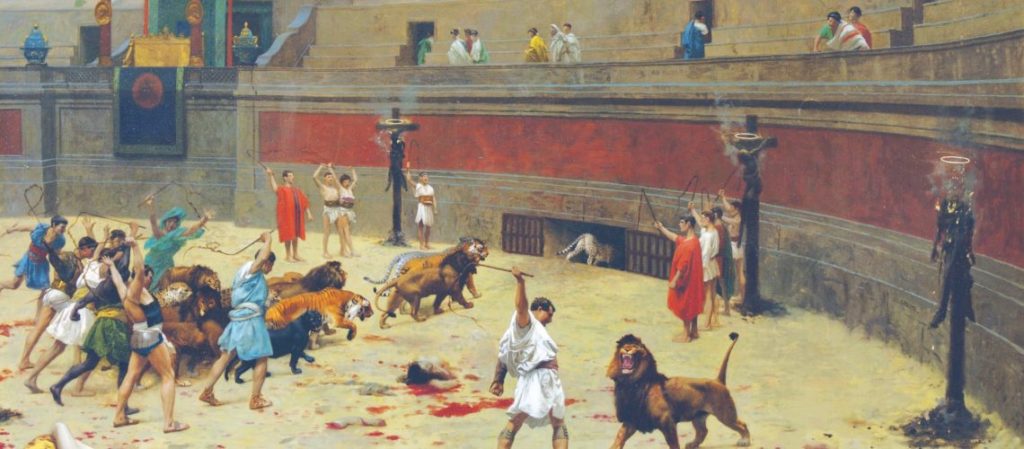

Titus brought his army to a Gentile city in King Agrippa II’s realm to the north to celebrate their victory with shows and spectacles. A large number of captives from Jerusalem met their end at the hands of gladiators or exotic beasts in the circuses. Some were forced to fight one another to the death.5Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

At Caesarea on the coast, Titus celebrated his brother Domitian’s birthday with many hundred of Jews slaughtered in games or by fire. The general then brought his men to Beirut and had an even grander celebration for his father Vespasian’s birthday with far more Jews executed in the same ways. He then went to Antioch in Syria which had a large Jewish population—and a community of earliest Christians. Titus was informed by local leaders that during the war some Jews had set fire to the public archives building, attempting to thereby erase the debts of the poor. The city officials asked Titus to allow them to evict all the Jews from their city, but the general would not allow this.6Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

Titus then finally sailed home to Rome where he and his father, the emperor, took part in a triumphal parade that brought the entire city together in celebration of Roman military might. Enormous banners, some 30 feet tall, were held aloft displaying artists’ realistic and gory depictions of a great many scenes from the war. Rebel leader John of Gischala and hundreds of the most fearsome-looking Jewish rebels had been dressed in fine garments and were paraded before the crowds. Then came a display of the most impressive booty the Romans had looted. Foremost among these was the giant seven-branched candelabrum made of gold that had been housed in the grand chamber of the Jerusalem Temple. A triumphal arch stands in Rome to this day depicting soldiers carrying the menorah in this procession. The sacred scrolls of the Jewish scriptures from the Temple were also displayed to the crowds as a spectacle.7Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

Finally, the rebel general Simon Bar-Giora, having been paraded through the city and reached the Temple of Jupiter, had a rope put around his neck. He was dragged over to the spot reserved for killing condemned criminals, tormented a bit, and then executed. At the announcement of his death, the crowd erupted in cheers, for the war was now over. After many sacrifices to their gods and much feasting among the people, emperor Vespasian announced he would commission a new temple in the city dedicated to Peace. When it was completed, it became the home of all the most precious items looted from the Jews.8Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

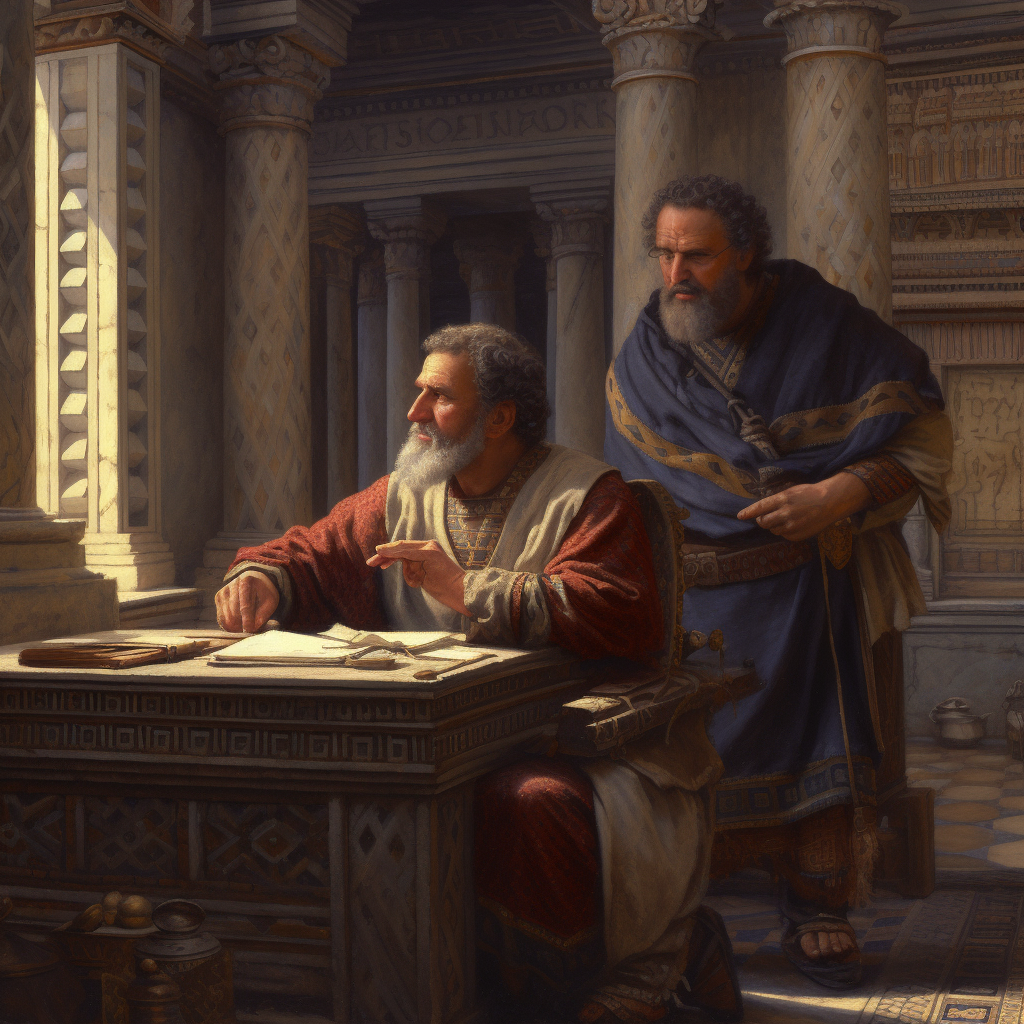

Ben-Matityahu had sailed with Titus to Rome, and there emperor Flavius Vespasian paid him the highest respects, formally adopting him into the imperial family. He would henceforth no longer be known by his Jewish birth name Joseph Ben-Matityahu, but by his new Roman name Flavius Josephus. He was gifted an apartment in the emperor’s house and several parcels of land in Judah that he would own tax-free. And he was awarded a comfortable annual pension to live off of, freeing his time to compose an official history of the war.9Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

Machaerus and Masada

Though the vast majority of rebels had been killed at Jerusalem or sold as slaves, and victory now declared by Rome, there remained a few last bastions of revolutionaries holding out in protected strongholds in Judah. Lest their spirit of revolt spread to neighboring lands, Titus now ordered general Lucilius Bassus and his legion of soldiers to destroy them. His first target was the fortress of Machaerus first built by the Maccabees, heavily fortified by King Herod, and the site of the execution of John the Baptist. Located atop a hill with steep approaches on all sides, there was both a small lower city area and a higher fortress overshadowing it.10Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

The fanatical rebels manned the fortress area while Jewish refugees from the war filled the lower city. As the Romans began preparations for their assault, they were under constant rebel harassment. A commander of these guerilla tactics named Eleazar had just completed a successful raid, but was then captured by the Romans. Bassus had him stripped naked and severely whipped in front of the fortress walls. Eleazar was beloved by the people of the lower city, though, and when Bassus now erected a cross to have him crucified, the citizens could not bear it. They quickly came to terms with the Romans, surrendering the lower city to them with guarantees of their and Eleazar’s safety in fleeing. The rebels in the fortress above then had little choice but to battle the Romans, but they were quickly overpowered. A few escaped, but over a thousand were slaughtered, and their wives and children sold into slavery.11Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

At this time, a letter arrived from Vespasian written to the Roman leaders in Judah, instructing them to immediately transfer ownership of all the land of the entire province—including all its cities—to the emperor. And whereas the Jews had always paid an annual tax for the upkeep of the Jerusalem Temple, now that it was destroyed, Vespasian ordered that this same amount now be paid annually by all Jews directly to Rome.12Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

Bassus succeeded in taking all the forts in Judah except one, and then he died and was replaced by Flavius Silva who in 73 CE, brought a few thousand Roman troops to the last bastion of rebel resistance, Masada. This was by far the least accessible of the fortresses built by King Herod, set atop a very tall butte with cliff walls on all of its sides, accessible only by twisting narrow switchbacks. Herod had a lavish palace built there, and the complex had sufficient agriculture on the top of the butte—as well as rain catching cisterns— to sustain a large force of soldiers indefinitely, making it virtually impervious to siege. Control of the fort had been in rebel hands since the revolt began seven years earlier. Less than 1,000 Zealots were holed up at Masada, and their leader was another man named Eleazar who was a descendant of Judas of Galilee who had begun the Tax Revolt against the Romans some 70 years before.13Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

Silva established the main Roman camp on another shorter hill directly adjacent to the fortress, but separated by a deep canyon. He ordered his men and many Jewish prisoners of war to haul massive amounts of earth and stones into the chasm below and slowly build up a ramp climbing from their camp up to the fortress wall, bridging the canyon. A massive siege tower with a built-in battering ram was then laboriously pushed up the ramp and into place. But when the wall was breached and the soldiers rushed inside, they found that everyone inside had committed suicide save for two women and five children found hiding. One woman had heard Eleazar’s final words to his fellow Zealots, proclaiming, “We resolved long ago never to be slaves to the Romans or anyone besides God. We were the first to revolt and are the last to fight. We thank God for the opportunity to die bravely in a state of freedom.”14Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

These final fighters of the war were almost certainly Essenes. Their method of suicide matched that of the men trapped in a cave with the turncoat Ben-Matityahu after the fall of Jotapata: lots were drawn, and each man was called upon to kill his comrade to avoid the Jewish prohibition against taking one’s own life.15Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books. In addition, and more conclusively, several writings—including apocalypses—have been found by modern archeologists among the ruins of Masada that are otherwise only known from the Essene writings discovered among the Dead Sea Scrolls. Ritual baths were also found on the site,16Schiffman, L. (2019). Masada and its scrolls. The Jerusalem Post. https://www.jpost.com/israel-news/masada-and-its-scrolls-610486 supporting the notion that the Jews who made a last stand there were daily ritual bathers as well.

A significant number of Zealot rebels managed to escape Masada and other sieges and scattered to various places including Alexandria in Egypt. Those who were tracked down and caught were subjected to extremes of torture, but bore it unflinchingly. The Romans marveled that even the children among them could not be compelled to declare that the emperor was their Lord. This matches descriptions of Essenes’ behavior during the war who were even said to have laughed at their torturers in their efforts to break their will.17Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books. It also matches later descriptions of the earliest Christian martyrs and their utter refusal to call anyone Lord but God and Jesus even on pain of death in the arena or by fire.18Bowersock, G.W. (2002). Martyrdom and Rome. Cambridge University Press.

When the Zealots in Egypt began urging the Jewish population there to revolt, Vespasian responded by ordering the destruction of the Jewish Temple there—the one that had been constructed by supporters of the ousted high priest Onias IV just before the Maccabean Revolt. But such measures could not contain the messianic fervor of the Jews across the empire. In neighboring Cyrene (today’s eastern coast of Libya), yet another would-be messiah, a weaver named Jonathan gained a large following and led them into the wilderness, promising to show them many signs and wonders. The Roman governor brought cavalry against the unarmed Jewish crowds who followed him, killing many, and capturing others including Jonathan himself who was brought in chains to Rome. There he made accusations against several prominent Jews including Flavius Josephus, but Vespasian dismissed his claims and had him tortured and burned alive.19Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

Flavius Josephus Publishes His History of the War

Putting to use the great influx of riches brought in from the despoiled nation of Judah, in the heart of Rome, on a plot of land that had been desolated by the Great Fire about 16 years earlier, Vespasian now began construction of the largest ancient stadium ever built.20Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books. In addition to a team of highly trained architects and a great many skilled craftsmen, the structure was almost certainly also built in part by slaves brought as captives from Judah. When completed 10 years later, it could accommodate up to 80,000 spectators, and was known as the Flavian Amphitheater.21“BBC’s History of the Colosseum p. 1”. Bbc.co.uk. 22 March 2011. Today we know it as the Colosseum, though that nickname derives from its having been built immediately adjacent to the colossal statue of the emperor Nero that stood 98 feet tall (equivalent of today’s Statue of Liberty without the base she stands on). Vespasian had recently had the colossus’s head altered to represent the Roman sun god Sol rather than the former emperor.22Colossus of Nero. Colosseum.Info. https://colosseum.info/colossus-of-nero/ While the Colosseum can still be visited today, Nero’s colossus stood only a few hundred years. Though stripped of its marble coating, the statue’s base remained viewable until its removal by Benito Mussolini in 1936.23Nash, Ernest. 1961. Pictorial Dictionary of Ancient Rome, Volume 1. (New York: Frederick A. Praeger)

In 75 CE, The Jewish War by Flavius Josephus was published, first in his native language of Aramaic and then reworked for a Greek-speaking audience. Vespasian pushed for the work to be released and disseminated as quickly and as widely as possible. One of his main aims was for the book to strongly discourage any further rebellion from Jewish communities that were still experiencing unrest in Babylon, Egypt, Cyrene, and other areas of the empire.24Denova, R. (2021.) Flavius Josephus. World History Encyclopedia. https://www.worldhistory.org/Flavius_Josephus/

Josephus’s writings belittle his fellow countrymen at every turn, referring to rebels as “robbers”, impugning their motives, and blaming them for Vespasian’s and Titus’s every brutality, especially the burning of the Temple. He portrays himself as a lifelong pro-Roman Pharisee who very reluctantly and magnanimously agreed to his position as rebel commander in Galilee. It is written throughout in a style that glorifies not just the Romans, but Josephus himself, portraying his every action as the work of a brilliant strategist who is a brave hero, and paragon of moral virtue.25Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books. With all its flaws, his book is nonetheless our primary source of knowledge about the time periods he covers, from the start of the Maccabean revolt up through the destruction of Jerusalem.

The survival of Josephus’s writings through the millennia has everything to do with their popularity among later Christians. Interestingly a church elder writing in the early 200s CE mentions his annoyance at not being able find any references to Jesus in Josephus’s books. But not terribly long after that complaint, there are writings from later Christians who do have mentions of Jesus and the Christians in their copies of Josephus. What they discovered was a one paragraph summary of Jesus’s life as presented in the gospels which had been awkwardly inserted into the text.26Eisenman, R.H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin. Modern scholars have long considered this passage to be an interpolation on multiple grounds, not least of which is that Josephus is consistently vehemently against any and all Jewish would-be messiahs and their followers.27Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press. Though his original writings almost certainly did not mention Jesus,28Carrier, R. (2012). Origen, Eusebius, and the Accidental Interpolation in Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 20.200. Journal of Early Christian Studies 20(4), 489-514. https://doi.org/10.1353/earl.2012.0029. Josephus does seem to have developed connections with Christians in Rome. In fact, it is likely that his books were translated into Greek by the same Epaphroditus who was a friend of the Apostle Paul and the secretary of Nero.29Eisenman, R.H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin. Josephus would go on to dedicate both of his next two books to Epaphroditus.

Later Christians of the 100s CE and onward, influenced by the gospels, would tend to view the destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans as a righteous punishment by God for the Jews having killed Jesus. Revealingly, though, two different early church elders later wrote of their puzzlement when, while reading the writings of Flavius Josephus, they came upon a passage in which the author states that after the war, most Jews believed that the catastrophe had been visited by God on the Jews for their having killed James the Just. Only a few generations later after these reports, however, this troublesome passage was no longer present in the copies of Josephus’s works read by later church elders.30Eisenman, R.H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin.

The obliteration of the city where James, Peter, and the original apostles headed the community of “the Saints”, “The Poor”, or “those of The Way” would have dealt a huge blow to the original Christian church. Their unique brand of theology, rituals, and way of living—their adherence to the Laws of Moses, vegetarian diet, prizing of chastity, frequent bathing, veneration of James the Just, and faith in the existence of the heavenly Lord Jesus, soon to usher the End Times—managed to survive in several areas of Syria, Egypt, the remaining cities of Judah, and lands to the east into Mesopotamia, but the original Christian church had effectively been decapitated.

Jerusalem’s destruction altered the course of Judaism forever. For nearly 500 years, the Jews had a god who was believed to be literally residing among them in their holy city. Their core form of worshiping God was the countless animal sacrifices performed there on the sacred altars by the ritually purified priests. The Temple had also been a vital gathering place for Jews from across the empire and beyond, especially at the annual festivals. By the end of the war, the Romans had learned the distinctions between Jewish sects, and actively sought to suppress those doctrines and leaders that pushed the people toward revolt, while supporting those willing to be docile and teach their adherents peaceful ways and obedience to Roman authority.31Eisenman, R.H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin.

Rabbi Yochanan Ben-Zakkai, whose disciples had smuggled him out of Jerusalem in a coffin, was now granted by Vespasian the right to create a Jewish academy in Yavneh in Galilee. This school and its Pharisaic worldview and theology, and its official Roman approval, would shape the dominant form of Judaism up to modern times.32Hezser, Catherine (1997). The Social Structure of the Rabbinic Movement in Roman Palestine. Mohr Siebeck. Meanwhile, anything the Rabbis thought resembled the dangerous beliefs of the Zadokites, Zealots, Essenes, or Earliest Christians was assiduously removed from the religion or suppressed. Any of the scriptures especially influenced by Zoroastrianism, such as the Book of Watchers, Enoch-related writings, Jubilees, and many other apocalypses—were spurned. Books like 1 and 2 Maccabees, which told the history of the Jews during their years of independence, were rejected for their glorification of rebellion and martyrdom.33Eisenman, R.H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin. All this had the effect of further separating what would become known as Rabbinic Judaism from the fanatically messianic form of Judaism out of which came the nascent Christian movement led by Peter and James and co-opted by Paul.

In fact, the form of hijacked Christianity preached by the apostle Paul (being Gentile-friendly, pro-Roman, anti-Jewish Law, and largely anti-Jewish) must have benefitted immensely from the war’s catastrophes. Far fewer competing missionaries from Peter and James’s church would have survived to put a check on the spread of Paul’s teachings. Paul’s successors would press that advantage to become the dominant form of Christianity despite his having been the enemy of the movement’s actual founders, and despite preaching doctrines they considered anathema.

Vespasian and Vesuvius

In addition to the victory over the Jews and the construction of the Colosseum, Vespasian’s 10-year reign as emperor saw the expansion of Rome’s control over Britain,34C. Suetonius Tranquillus, Divus Vespasianus, chapter 24. LacusCurtius. and the publication of Pliny the Elder’s Natural History—an encyclopedic collection covering the latest understandings of geography, anthropology, zoology, agriculture, pharmacology, astronomy, and more. The book was dedicated to the emperor’s son, Titus.35Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2019, January 24). Natural History. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Natural-History-encyclopedic-scientific-by-Pliny-the-Elder In June of 79 CE, Vespasian suffered a serious infection that left him dangerously ill. Referencing the tradition of deifying Roman emperors upon their death, Vespasian is said to have quipped, “Dear me, I think I’m becoming a god.”36Suetonius, Life of Vespasian, 23:4 Upon his death days later, he was succeeded by Titus.

In the fall of that same year, Pliny the Elder was at his house on the Bay of Naples when he and his family observed a massive plume of dark smoke roiling upward for miles over Mount Vesuvius across the bay. Like all those in the region at the time—even having written an exhaustive book on natural history—Pliny did not understand what he was seeing. When lava became visible pouring down the sides of the mountain, it was interpreted as ordinary fire rather than a river of molten rock. Pliny was about to head out for a better look when a boat arrived with a message from a close friend in Pompeii, desperately requesting ships for an evacuation by sea.37Sigurðsson, Haraldur; Carey, Steven (2002). “The Eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79”. In Jashemski, Wilhelmina Mary Feemster; Meyer, Frederick Gustav (eds.). The Natural History of Pompeii. Cambridge UK: The Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge. pp. 37–64.

There would be no time. Soon massive clouds of superheated gas and volcanic debris covered the entire area surrounding Pompeii as well as the seaside resort city of Herculaneum where great numbers of bodies have been excavated in boathouses by the shore—citizens waiting for a rescue that would never come. Pliny managed to cross the bay with some friends, but could not get close enough to land his boat near any population centers. When they did go ashore a distance away, Pliny was in utter fascination and wanted to move closer to the phenomena, declaring “fortune favors the brave.” But fortune did not favor Pliny the Elder who strode toward the volcano, only to choke on toxic gasses and drop dead. The other members of his party managed to escape back across the bay and told their stories and observations to his 17-year-old adopted nephew Pliny the Younger as they all fled the region to safety.38Sigurðsson, Haraldur; Carey, Steven (2002). “The Eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79”. In Jashemski, Wilhelmina Mary Feemster; Meyer, Frederick Gustav (eds.). The Natural History of Pompeii. Cambridge UK: The Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge. pp. 37–64.

Later in life, Pliny the Younger had an exchange of letters with his close friend Tacitus, a Roman historian. When Tacitus inquired concerning the events surrounding the death of his father Pliny the Elder, the nephew obliged him with an extensive account of his uncle’s fateful last day, including eyewitness reports. When Tacitus followed-up by asking what Pliny the Younger himself did in the immediate aftermath of his uncle’s death, he received a detailed account of that as well.39Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press.

Had Jesus lived a life on earth and been crucified as a criminal amid eyewitnesses, it has been pointed out that this is exactly the sort of exchange we should expect to find between the earliest Christians. Surely devout new converts would be dying to hear detailed accounts of Jesus’s life and death, his teachings and actions. But as we have seen, there is no record of such writings.40Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press. In the documents we do have, such as the letters of Paul, he responds to many questions and concerns from members of his churches, but not a single one asks for eyewitness or even secondhand witness to any event in Jesus’s life. No one asks for a clarification of a quote from Jesus or the meaning of one of his parables. No one asks if he really walked on water or raised people from the dead. No one asked if he married or had children, or any of the things one would reasonably expect if they were being taught that Jesus lived a life on earth just a decade or two before.

Continue Reading:

Footnotes

- 1Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

- 2Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

- 3Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

- 4Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

- 5Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

- 6Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

- 7Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

- 8Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

- 9Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

- 10Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

- 11Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

- 12Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

- 13Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

- 14Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

- 15Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

- 16Schiffman, L. (2019). Masada and its scrolls. The Jerusalem Post. https://www.jpost.com/israel-news/masada-and-its-scrolls-610486

- 17Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

- 18Bowersock, G.W. (2002). Martyrdom and Rome. Cambridge University Press.

- 19Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

- 20Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

- 21“BBC’s History of the Colosseum p. 1”. Bbc.co.uk. 22 March 2011.

- 22Colossus of Nero. Colosseum.Info. https://colosseum.info/colossus-of-nero/

- 23Nash, Ernest. 1961. Pictorial Dictionary of Ancient Rome, Volume 1. (New York: Frederick A. Praeger)

- 24Denova, R. (2021.) Flavius Josephus. World History Encyclopedia. https://www.worldhistory.org/Flavius_Josephus/

- 25Beasley, B. (2015). Flavius Josephus: The Jewish Wars. Living Stone Books.

- 26Eisenman, R.H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin.

- 27Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press.

- 28Carrier, R. (2012). Origen, Eusebius, and the Accidental Interpolation in Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 20.200. Journal of Early Christian Studies 20(4), 489-514. https://doi.org/10.1353/earl.2012.0029.

- 29Eisenman, R.H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin.

- 30Eisenman, R.H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin.

- 31Eisenman, R.H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin.

- 32Hezser, Catherine (1997). The Social Structure of the Rabbinic Movement in Roman Palestine. Mohr Siebeck.

- 33Eisenman, R.H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin.

- 34C. Suetonius Tranquillus, Divus Vespasianus, chapter 24. LacusCurtius.

- 35Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2019, January 24). Natural History. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Natural-History-encyclopedic-scientific-by-Pliny-the-Elder

- 36Suetonius, Life of Vespasian, 23:4

- 37Sigurðsson, Haraldur; Carey, Steven (2002). “The Eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79”. In Jashemski, Wilhelmina Mary Feemster; Meyer, Frederick Gustav (eds.). The Natural History of Pompeii. Cambridge UK: The Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge. pp. 37–64.

- 38Sigurðsson, Haraldur; Carey, Steven (2002). “The Eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79”. In Jashemski, Wilhelmina Mary Feemster; Meyer, Frederick Gustav (eds.). The Natural History of Pompeii. Cambridge UK: The Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge. pp. 37–64.

- 39Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press.

- 40Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press.