Chapter 16

The Second Gospel

The Gospel of Jesus Christ 2.0

In the years after its initial publication, we can surmise that the first gospel was copied and shared among various communities and spread eastward around the Mediterranean from Rome. Each new community coming into contact with the anonymous document may have been split over whether it was a report of actual history or allegory for higher level doctrine. One thing we can say for certain, however, is that within less than a decade, a trend would begin in which other writers would take this document and feel qualified to make significant changes to it, adapting it to the beliefs and needs of their own churches. This process is how the second gospel came to be composed1Note: While most scholars currently hold the gospel known to us as Matthew to be the second-written gospel, I believe this is based on outmoded scholarship and faulty logic as explained here: https://www.alangarrow.com/synoptic-problem.html—a gospel no longer extant, but whose material has been largely pieced together by modern scholars who recognized the extent to which the gospel known to us as Luke later incorporated nearly all of its material.2BeDuhn, J. (2013). The First New Testament: Marcion’s Scriptural Canon. Polebridge Press.

This writing—not a truly new gospel, but a revision of the first—was likely composed in a city on the west coast of Asia Minor.3Attridge, H.W. The Gospel of Luke: A Novel for Gentiles. PBS Frontline. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/religion/story/luke.html#:~:text=Luke%20was%20probably%20writing%20in,places%20like%20Ephesus%20or%20Smyrna. This was a region frequented by Paul as well as and other apostles about whom Paul frequently complained. The area’s population was dominated by Gentiles, but included minority Jewish populations in many of its larger cities. While there isn’t enough data available to take even an educated guess about the identity of the author, we can be certain that they had a copy of the first gospel in front of them as they wrote.

Changes to the gospel they received begin right from the start. Seeming to have taken issue with the idea of Jesus needing the baptism of John for the cleansing of sins, much less the notion of Jesus being tempted by Satan, the second gospel’s author removes these opening stories and begins his revised story of Jesus’s ministry on Earth with the succinct introduction: “In the fifteenth year of Tiberius Caesar, when Pilate was governing Judea, Jesus came down to Capernaum, a city of Galilee.”4BeDuhn, J. (2013). The First New Testament: Marcion’s Scriptural Canon. Polebridge Press. This sets the story in 26 CE, a much more precise date than the first gospel offers, and suggests that whatever the first gospel’s author thought about the historicity of their writing, the second gospel’s author seems to more clearly intend for their account of Jesus’s life to be taken literally.

Though the author does not allow John to baptize Jesus—and later skips over the story of the Baptist’s death by beheading—John does make appearances in the second gospel, and is very highly praised. Jesus, in fact, is said to refer to John as “the greatest among those born of women”.5BeDuhn, J. (2013). The First New Testament: Marcion’s Scriptural Canon. Polebridge Press.

This particular phrasing leaves us to wonder: does the author of the second gospel believe Jesus was born of a woman? If so, how could he describe John this way, implying that John is greater even than himself, the very Son of God? Or is it that the author does not believe Jesus was born of a woman? If that’s the case, then why does he retain the story from the first gospel in which Jesus is told by a disciple “Your mother and your brothers have stood outside wanting to see you”? This brief mention of Jesus’s family, in which he snubs them, is the only appearance they make in the second gospel. None of his family members are mentioned by name, and none are given any lines of dialog. It leaves open the question: when the author began this work by stating “Jesus came down to Capernaum”, did he mean that he “came down” from some other unspecified earthly location, or did he mean directly from heaven?6BeDuhn, J. (2013). The First New Testament: Marcion’s Scriptural Canon. Polebridge Press.

Even the link to Nazareth as Jesus’s hometown seems to be intentionally broken by this author, substituting nearby Capernaum as the starting point of Jesus’s ministry on Earth. When Jesus does visit a synagogue in Nazareth—whereas in the first gospel Jesus simply could work no miracles there and was disrespected by the residents—here he enrages the congregation so much that they run him out of town and are about to throw him off a cliff when he somehow passes through the crowd and escapes.7Luke 4:28-30. The Bible. New International Version. Some have read into this account the implication that Jesus was not fully physical, and could thereby pass through an angry mob like a ghost to escape, though this notion is gainsaid later in the gospel where Jesus’s corporeality is emphasized.

In this presentation of Jesus’s narrow escape from Nazareth, the second gospel’s author has taken a story from the first gospel and changed it to better suit his own beliefs or agenda. But for much of the second gospel’s narrative, stories from the first gospel are simply copied directly, or only very slightly reworded. This is the case for the next 10 stories in a row as Jesus begins his traveling ministry of healings and exorcisms. The author then decides to insert 5 original stories, the first of which is one of the most famous in all the gospels.8BeDuhn, J. (2013). The First New Testament: Marcion’s Scriptural Canon. Polebridge Press.

The Sermon on the Plain

In the narrative of the first gospel, Jesus and his disciples now come to a lakeside surrounded by a great multitude. While the author of that gospel immediately moves on from there, the second gospel’s author chooses this point to interrupt the narrative and use this setting to have Jesus deliver what is known today as the Sermon on the Plain—a discourse featuring several of the most famous ethical teachings of Jesus from any gospel, including all of the following:

- Blessed are you who are poor, for yours is the Kingdom of God.

- Blessed are you who hunger now, for you shall be satisfied.

- Blessed are you who weep now, for you shall laugh.

- Woe to you who are rich, for you have received your comforts.

- Woe to you who are full now, for you shall hunger.

- Woe to you who laugh now, for you shall mourn and weep.

- Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you.

- If you love those who love you, what credit is that to you? For even sinners love those who love them.

- Bless those who curse you, pray for those who abuse you.

- To him who strikes you on the cheek, offer the other as well.

- From him who takes away your coat, offer your shirt as well.

- Give to everyone who asks of you, and of him who takes your possessions do not ask for them back.

- As you wish that men would do to you, do so to them.

- Judge not, and you will not be judged.

- Condemn not, and you will not be condemned.

- Forgive, and you will be forgiven.9Luke 6:20-37. The Bible. New International Version.

Though these sayings are here put in the mouth of Jesus, seven of them (those in bold) appeared in the writing we examined earlier, The Teaching of the Twelve Apostles (also called The Didache).10Didache. Early Christian Writings. https://www.earlychristianwritings.com/didache.html There they were notably not presented as teachings of Jesus at all, for, as we saw, The Teaching of the Twelve Apostles would seem to date to the time of Peter, James, and Paul—long before there was any notion of a Jesus who walked the earth delivering sermons to crowds of followers. So it is clear that in addition to his copy of the first gospel, the second gospel’s author also had a copy of The Teaching of the Twelve Apostles before him, and felt comfortable selecting a number of its teachings and portraying a historicized Jesus as having spoken them during his earthly life. As for the teachings in the Sermon on the Plain which are not taken from The Teaching of the Twelve Apostles, we can only guess their origin. The author may have had access to other early Christian writings—now lost to us—and similarly copied select teachings from those documents, or these other sayings may be original compositions by the author.

Another notable detail about this Sermon on the Plain is its audience. The first gospel describes the crowd at the lakeside having come to see Jesus from Jewish locales like Judah, Jerusalem, Idumea, and beyond the Jordan—as well as the Gentile locales Tyre and Sidon.11Mark 3:7-8. The Bible. New International Version. But in the second gospel, the author removes all the Jewish locations so that the sermon is delivered to what would seemingly be an all-Gentile audience.12BeDuhn, J. (2013). The First New Testament: Marcion’s Scriptural Canon. Polebridge Press. This is in line with the author’s general trend of featuring and favoring Gentiles over Jews throughout the second gospel. At one point Jesus is depicted as praising the faith of a Gentile as being greater than anything he’s found among the Jews.13Luke 7:6-9. The Bible. New International Version. At another point, Jesus notes that in the time of the Elisha, that prophet could have healed many, but chose only to heal a Syrian.14Luke 4:27. The Bible. New International Version. And after healing ten lepers, Jesus notes that only one of them, a Samaritan, gave him thanks.15Luke 17:11-19. The Bible. New International Version. This anti-Jewish sentiment would only snowball with each gospel written.

After the Sermon of the Plain concludes, it is followed by 3 more new stories, then the author resumes copying or rewording an almost unbroken string of 21 stories in their original order from the first gospel. This is followed up by an almost unbroken string of 27 new stories inserted into the narrative framework of the first gospel. In the passion section of the second gospel, 25 stories are copied in original order from the first gospel with 5 original stories inserted therein. Finally, at the very end of the second gospel, 5 new stories are added that take place after the end of the 1st gospel, introducing the first narratives of Jesus appearing to the disciples after his death and burial.16BeDuhn, J. (2013). The First New Testament: Marcion’s Scriptural Canon. Polebridge Press.

Other Changes to the First Gospel

The author of the second gospel puts emphasis on listening to Jesus and putting his teachings into practice. Whereas the first gospel has Jesus reject his own family, asking “Who are my mother and my brothers? …Whoever does the will of God is my brother and mother,”17Mark 3:34-35. The Bible. New International Version. the second gospel alters the second part to read “Whoever hears my words and puts them into practice is my mother and my brothers.”18Luke 8:21. The Bible. New International Version. In an added parable he also compares “everyone who comes to me, hears my words, and puts them into practice” to a wise man who built his house properly.19Luke 6:47-49. The Bible. New International Version.

Overall, the second gospel seems to be of two minds concerning the continuing validity of the Law of Moses. The author retains material from the first gospel in which Jesus affirms the necessity of following the commandments20Stating: You know the commandments: “You shall not murder; You shall not commit adultery; You shall not steal; You shall not bear false witness; You shall not defraud; Honor your father and mother.” 20BeDuhn, J. (2013). The First New Testament: Marcion’s Scriptural Canon. Polebridge Press. (and in addition, the teaching that one must sell all one’s possessions and give the money to the poor).21BeDuhn, J. (2013). The First New Testament: Marcion’s Scriptural Canon. Polebridge Press. But in newly added material, the author has Jesus pronounce that “The Law and the Prophets lasted until John [the Baptist], and since then the Kingdom of God has been proclaimed”,22Luke 16:16. The Bible. New International Version. which isn’t quite an entirely clear statement that the Law of Moses no longer applies to his followers, but it is very much open to that interpretation and would be taken that way by nearly all Gentile Christians.

The “Kingdom of God” that is proclaimed by Jesus becomes even more vaguely described in the second gospel. The first gospel’s author used the phrase to refer to the End Times (“There are some standing here who will not taste death until they see that the Kingdom of God has come with power”)23Mark 9:1. The Bible. New International Version. or heaven (“It is better for you to enter the Kingdom of God with one eye than to have two eyes and to be thrown into hell”),24Mark 9:47. The Bible. New International Version. whereas the second gospel’s author retains these two uses, but also states, “The Kingdom of God is not coming in a way that can be seen. Nor will they say, ‘Look here!’ or ‘There!’ For, behold: the Kingdom of God is within you.”25Luke 17:20-22. World English Bible. No clarification of this statement is offered, but it could be interpreted as the author moving away from the core belief among early Christians that the End Times were expected to begin at any moment. Indeed, the author also removes the line from the first gospel in which Jesus tells his disciples that all the events of the End Times will happen within their lifetimes.

But despite the fact that the second gospel seems to treat the Kingdom of God more fluidly, and may not expect the End Times to begin quite as imminently, it clearly does expect all the cataclysmic events described by the first gospel to occur at some point. All the descriptions Jesus provides to his disciples of what will occur before the resurrection are faithfully copied into the second gospel from the first. In the meantime, in some sense that is not very clear from the text, the phrase “the Kingdom of God” is being imbued with a new meaning—something believers have access to in the present while they await the End.

Family relations are treated more harshly in the second gospel, with Jesus announcing that anyone who does not leave their family behind cannot be his disciple;26Luke 14:26. The Bible. New International Version. and saying that anyone who wants to finish plowing a field or say goodbye to their family27Luke 9:61-62. New English Translation.—or even to see to their own father’s funeral28Luke 9:59-60. The Bible. New International Version.— before leaving everything behind and following him, is not fit for the Kingdom of God.

Concerning the institution of marriage—though its ambiguity leaves things open to various interpretations—the second gospel alters a passage from the first gospel so that it reads: “The children of this age marry and are married; but those counted worthy by God of that age and the resurrection of the dead neither marry nor are married, because neither do they die anymore; for they will be like angels, because they are children of God and of the resurrection.”29Luke 20:34-35. The Bible. New International Version.

While the author may have only intended to say that after the resurrection, faithful Christians will become like the angels, and therefore have no need for marriage, sex, or procreation; there were, at this time, a growing number of Christians, especially in Asia Minor and neighboring northern Syria, who were adopting a celibate lifestyle.30Heid, S. (2001). Celibacy in the Early Church: The Beginnings of Obligatory Continence for Clerics in East and West. Ignatius Press. This practice may be rooted in the stricter Essene communities’ shunning of marriage, sex, and procreation—an attitude carried forward by Peter, James, and the original Jerusalem church. Whether or not the author of the second gospel intended this passage to be taken in this way, such communities may have preferred such an interpretation so that such celibates could see themselves as “those counted worthy by God”.

One of the most notable additions in the second gospel is known as the parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus (a different Lazarus than the one famously raised from the dead in the later fourth gospel). In this well-told story—which some scholars believe is an adaptation of a tale originating in Egypt31The Interpreter’s Bible, Vol. 8. Abingdon Press.—a rich man lives in comfort all his life while a starving, diseased, homeless beggar named Lazarus lives just outside the walls of his home. When they both eventually die, Lazarus is carried up to heaven by angels and receives eternal comforts with the ancient Jewish patriarch Abraham at his side. The rich man, however, goes to hell where he experiences constant and unrelenting torture amid unquenchable flames. Now reduced to a pathetic beggar himself, the rich man calls out to Abraham, pleading for a drop of water to relieve his torments. But an unsympathetic Abraham explains that the fortunes of the rich and poor are reversed in the afterlife, and there is no escaping hell.32Luke 16:19-25. The Bible. New International Version.

This vision of eternal physical punishment after death dates back to the Enoch literature that, as we have seen, was first imported from Persian theology into Judaism three centuries before, and was adopted by Zadokites, Essenes, and the earliest Christians. In contrast, the developing and soon-to-be dominant sect of Rabbinic Judaism, guided by the influence of those such as Yochanan Ben-Zakkai—who snuck out of Jerusalem in a coffin and pledged loyalty to Rome—attempted to steer the Jews away from all the doctrines associated with the Essenes and other sects whose beliefs had proven dangerously conducive to revolt and endangered Jews everywhere.33Eisenman, R.H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin.

In addition to having lifted select ethical instructions out of The Teaching of the Twelve Apostles and put them in the mouth of Jesus in the Sermon of the Plain, the author of the second gospel also took that writing’s presentation of what is today known as The Lord’s Prayer. In a reworded form, he adds it to his revision of the first gospel, having Jesus instruct his disciples to pray as such: “Father, let your holy spirit come upon us. Let your kingdom come. Give us your sustaining bread day by day. And forgive us our sins. And do keep us from temptation.”34Luke 11:2-4. The Bible. New International Version.

Death and Resurrection Appearances

As the ministry section of the second gospel ends, the author mostly just reverts to copying the first gospel’s stories of the Last Supper and events leading to the crucifixion. One small but poignant addition to the scene at Golgotha is having Jesus say from the cross, “Father forgive them, for they know not what they do”.35Luke 23:34. The Bible. New International Version. This quote, as we have previously seen, was originally attributed to James the Just as his dying words as he was being executed. This bit of erasure of the man who presided over the earliest Christian community in Jerusalem—and, for a time, all of Christendom as the “bishop of bishops”—foreshadows his near-entire erasure from the history related by the book of Acts.

But this repurposed quote is not presented as Jesus’s final words. Whereas the first gospel had Jesus quote the scriptures as he was suffering, saying, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” This author, seemingly unable to stomach having the Son of God feel abandoned by the Father at his moment of death, has Jesus keep his cool, instead quoting from the Psalms, saying, “Father, I entrust my spirit into your hands.”36Luke 23:46. The Bible. New International Version.

At the empty tomb, the author makes minor changes to the account in the first gospel. Here, instead of being stopped by a young man in a white robe as they approached, the women now actually enter the tomb itself and see that the body of Jesus is missing. Only then do they see two men in shining clothing. And whereas the first gospel ends abruptly with the women telling no one of what they had seen, the second gospel writer changes this so that the women do the very opposite—they run off and do tell the disciples what they’ve seen, but all the disciples refuse to believe the women.37Luke 24:1-11. The Bible. New International Version.

Next, in the first-ever story of a post-death bodily appearance of Jesus, the author writes that two disciples are traveling along a road when the resurrected Jesus joins them—though they don’t recognize who he is. They talk for a while before Jesus finally berates them for their failure to believe him the many times he had predicted his own suffering and death.38Luke 24:1-32. The Bible. New International Version. This story may have been inspired by the strikingly similar story published in a work written by the Roman author Plutarch in 75 CE, relating the life of the mythical founder and first king of Rome, Romulus—who was also described as a Son of God, and who also had a life and death on Earth before making appearances to his followers, one of them as they traveled along a road between Rome and a nearby town.39Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press.

Following this, the second gospel has Jesus appear before all the disciples together, who mistake him for a ghost. Jesus proves to them that he has a physical body by having them examine his hands and feet (which presumably still have holes in them from his recent execution), and when this doesn’t fully convince them, he asks for something to eat, and consumes some broiled fish in their presence.40Luke 24:36-43. The Bible. New International Version.

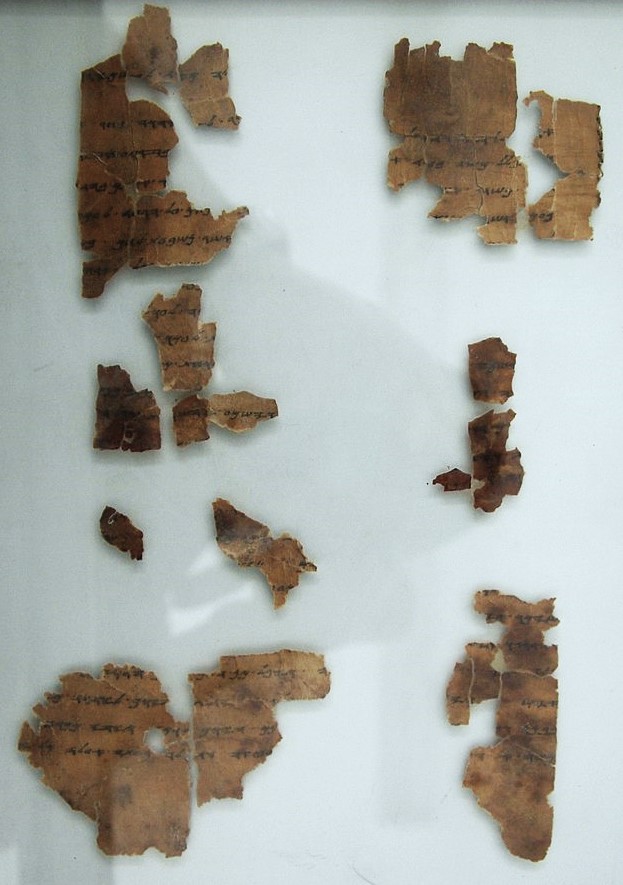

Because this second gospel has not survived in its original whole to this day, its content has been painstakingly reconstructed by scholars based on the extensive quotes and descriptions of it found in the writings of several ancient authors who had copies of it in front of them.41BeDuhn, J. (2013). The First New Testament: Marcion’s Scriptural Canon. Polebridge Press. Unfortunately, there are a number of sections of the original that remain opaque to us because we don’t have a record of them. This gap includes the very ending, about which we only have a single incomplete line of text which has Jesus sending out his disciples to “proclaim… to all the people”. This commissioning, absent from the first gospel, better ties together the story of Jesus’s life and death on Earth to the history of the earliest Christian movement which began with apostles being sent out to proclaim the good news that the heavenly Lord Jesus, long kept secret by God, had now been revealed to bring salvation.

The Fate of Flavius Josephus

During the Roman war against the Jews, general Titus had begun a love affair with Berenice, the half-Jewish sister of King Agrippa II.42Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications. This is the same Berenice and Agrippa who, according to the book of Acts, visited and were friendly with the apostle Paul while he was under house arrest in Caesarea.43Acts 25:23-27. The Bible. New International Version. They also provided crucial support to the Romans during the war. Upon the death of Vespasian, Berenice helped champion Titus as his rightful successor, and in 75 CE she came to Rome and lived in the imperial palace with the new emperor as his fiancée. But the Roman people were displeased at the notion of an eastern queen, and after much harsh public criticism, Titus sent her away.44Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

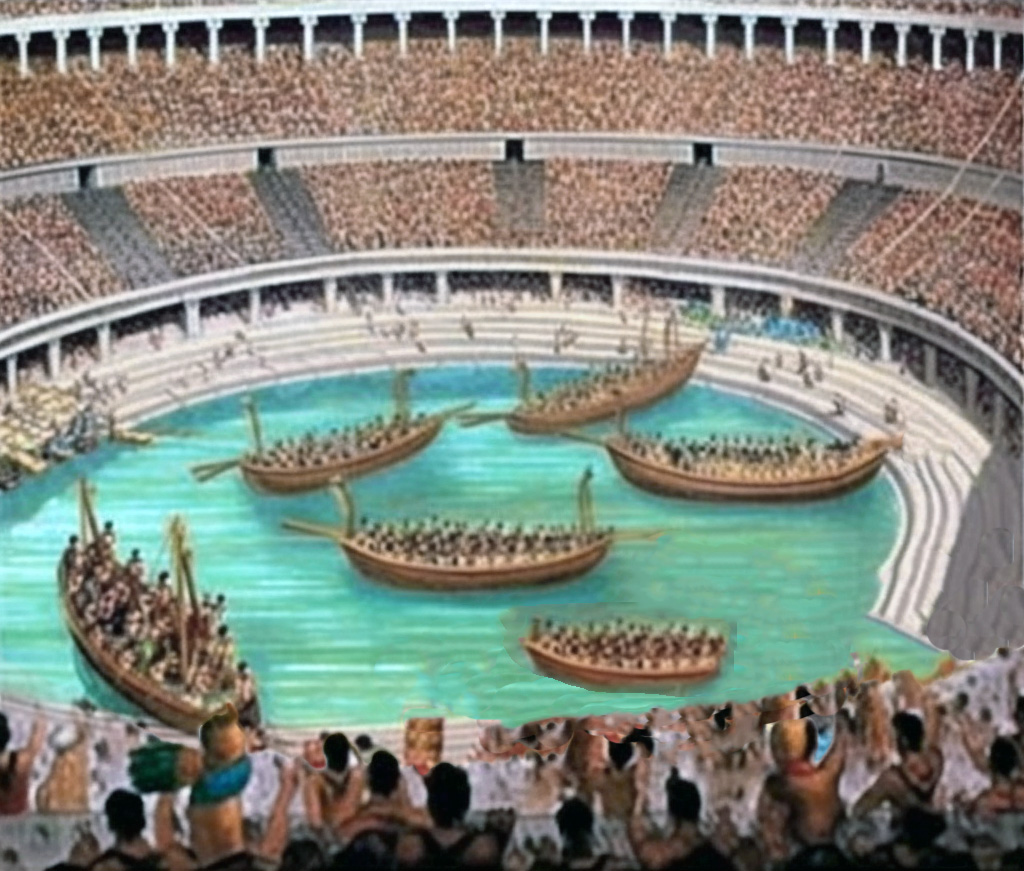

During his brief reign, Titus presided over the completion of the Flavian Amphitheater (the Colosseum) and its inaugural games which lasted 100 days. Events staged here over the years included wild animal hunts, gladiatorial combat, chariot races, fights between elephants and bears, and even mock naval battles for which the ground level was flooded to form a shallow sea.45Hopkins, K. & Beard, M. (2012). The Colosseum. Harvard University Press. A new public facility, the sprawling Baths of Titus, debuted at this time, as well, having been built on top of Nero’s Golden Palace.46Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars. Life of Titus 7.

Not long after this occasion, Titus fell ill of fever in 81 CE, and died soon after.47Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars. Life of Titus 10. Rumors circulated that the emperor had been poisoned by his younger brother Domitian who succeeded him.48Barrett, A.A. (2009). Lives of the Caesars. John Wiley & Sons. Whether out of devotion or to throw off suspicion, one this new emperor’s first acts was the deification of his late brother.49Suetonius. The Lives of Twelve Caesars. Life of Domitian 2. As ruler, Domitian dispensed with any pretenses of limited democracy that his father and brother had allowed, stripped the Senate of any real power, and established himself as an autocrat.50Gowing, Alain M. (1992). Review: The Emperor Domitian. Bryn Mawr Classical Review. Hoping to return the empire to the glory of the days of Augustus, Domitian took an active role in all aspects of government, military, construction, and public life. He expressed great concern with the morality of the people, and so strongly promoted traditional worship of the Roman gods and emperors. Adultery was punished by exile.51Jones, B. (2002.) The Emperor Domitian. Routledge. Castration was outlawed.52Ranke-Heinemann, U. (1990). Eunuchs for the Kingdom of Heaven: Women, Sexuality, and the Catholic Church. Translated by Heinegg, Peter. Doubleday Philosophers and mimes were banished from the capital.53Epictetus & Rolleston, T.W.H. The Teaching of Epictetus: Being the Encheiridion of Epictetus with Selections from the Dissertations and Fragments. Library of Alexandria.

The infamous Jewish turncoat cum Roman historian Flavius Josephus continued living under imperial favor during this time, and in 93 CE, published his second major work, The History of the Jews54Josephus. Antiquities, Book XX, chapter 11.—written for a Gentile audience, but with much pride and celebration of the author’s heritage. The book follows the story of the Israelites roughly as told in the Hebrew scriptures, from Genesis through the books of Kings, with occasional significant variations based on popular legendary embellishments from writings that didn’t make it into the Bible.55Louis Feldman. (1998). Josephus’ Interpretation of the Bible. University of California. More fascinating and valuable are Josephus’s telling of history during the otherwise poorly documented years between the Babylonian exile and the rise of the Maccabees, and carrying forward to the start of the Jewish-Roman War. Without his chronicle of these years, the history of the Jews during these times would be largely unknown to us. Toward the end of the same decade, Josephus published two more works: Against Apion, which defended the Jewish people from the cruel slanders of the notorious Alexandrian anti-Jewish sophist Apion Pleistoneices; and The Life of Flavius Josephus, a relatively short autobiography, defending himself from critics, and covering the parts of his life not already covered in his other works.

Though he considered himself a benevolent dictator, many considered Domitian a tyrant, who, like Nero before him, grew more unstable as his reign progressed. As the emperor’s enemies—real or perceived—grew in number, so too did his arrests and executions.56Jones, B. (2002.) The Emperor Domitian. Routledge. Shortly after the publication of his final book, Josephus disappears from the historical record. We do know that his publisher Epaphroditus—who the apostle Paul mentions as a “friend and co-worker”—was put to death by Domitian.57Tacitus. Annals. xv. 55. We further know that Flavius Clemens, a Roman noble who had married into the imperial family, was also executed at this time on charges of “atheism”, which was often a Roman euphemism for Judaism or Christianity.58Cassius Dio. Roman History lxvii. 14. So it is possible Domitian was having Jews and/or Christians (if they were even differentiated by Roman authorities at this point) in high places killed off, but we can’t be certain about the circumstances of Josephus’s demise.

Perhaps in retaliation for these murders, or simply to put an end to such executions, Flavia Domitilla—the wife of Flavius Clemens—now plotted with others to assassinate the emperor. To carry out the act, her slave Stephanus feigned an arm injury and wore a cast in which he concealed a dagger. Claiming to have discovered a plot against the emperor, the slave was granted an audience with Domitian who was promptly stabbed in the groin, and then seven additional times as he attempted to fight off his assassin who was, in the melee, himself fatally stabbed by the emperor. Upon Domitian’s death, the Senate voted to erase nearly all memory of him, so bringing an ignoble end to the Flavian dynasty of emperors.59Grainger, J.D. Nerva and the Roman Succession Crisis of AD 96-99. Routledge.

The “Epistle of Barnabas”

Toward the end of the first century,60Richardson, P. & Shukster, M.B. (1983). Barnabas, Nerva, and the Yavnean Rabbis. The Journal of Theological Studies, Volume 34, Issue 1. https://doi.org/10.1093/jts/34.1.31 a treatise was composed by an anonymous Christian author which was, decades later, ascribed to Barnabas—a man who was mentioned in the apostle Paul’s letters as an occasional traveling companion.61Galatians 2:9. The Bible. New International Version. This writing was considered important enough among some communities that it would later be included as part of the New Testament canon among certain churches into the 300s CE. The treatise is remarkable for its vehement anti-Jewish stance. Its core argument is that Judaism is a false religion and the Jews never understood their own scriptures at all. The Hebrew Bible, the author argues, was never intended to be taken literally, and every bit of it is allegory that, when properly interpreted, points to Jesus. It is therefore a Christian rather than a Jewish book.62Lightfoot, J.B. The Epistle of Barnabas. Early Christian Writings. https://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/barnabas-lightfoot.html

Like the epistles to the Hebrews and the epistle of Jude, this writing makes reference to—even quotes as scripture—the Enoch literature prized among the Essenes and earliest Christians. The author also seems to be familiar with the second gospel, quoting a line from its Parable of the Banquet: “Many are called, but few are chosen,” though the saying is not here attributed to a specific work, but only introduced by the phrase “As it is written…”.63NOTE: It’s also possible that this phrase was simply a well known cliche the author expected his audience to be familiar with. The ministry of Jesus on earth as described in the second gospel is alluded to multiple times, seeming to indicate that the author takes for granted that Jesus led a life among humans on Earth. The disciples are not named, though, and interestingly, the author says that the apostles chosen by Jesus were the most extreme of sinners—a description not found in any known writing up to this time.64Lightfoot, J.B. The Epistle of Barnabas. Early Christian Writings. https://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/barnabas-lightfoot.html

Despite showing some level of familiarity with at least one gospel, when the author describes any aspect of Jesus’s sufferings and crucifixion, he consistently chooses to describe these events using only quotes from the Hebrew scriptures that have been removed from their original context65Lightfoot, J.B. The Epistle of Barnabas. Early Christian Writings. https://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/barnabas-lightfoot.html—the same methodology employed by all Christian writers up to this time, even, for the most part, the two gospels themselves.

Among the many examples offered to show how terribly the Jews have failed to understand their scriptures, the author argues that the ritual of circumcision was never intended to be taken literally. Syrians, Arabs, and Egyptians practice circumcision as well, it is pointed out, but surely they have no covenant with God! The original command by Yahweh to Abraham to circumcise his entire household is then examined, and here the author uses an interpretive method known as gematria—the same technique famously used by the author of the Revelation of John, in which the “number of the beast” is said to be 666, which most scholars take as an alpha-numeric cipher for Nero. Here the 318 members of Abraham’s household (including slaves) is interpreted as pointing to the initials in Greek commonly used as shorthand for “Jesus”, and a leftover letter T is said to represent the cross.66Lightfoot, J.B. The Epistle of Barnabas. Early Christian Writings. https://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/barnabas-lightfoot.html

The author’s interpretive skills are also applied to the Jewish dietary restrictions, which again, are said to have been intended strictly as allegory. Rather than a prohibition against eating pork, what God intended for the Jews to understand was that they should not associate with people who behave like pigs. Yet there are, according to the author, several creatures that truly should not be consumed. The hyena is off limits because “this animal changes its nature every year, at one time being male, the next time female.” Eating rabbits is prohibited due to the fact that “the rabbit adds an orifice each year, having as many holes as years it has lived.” And likewise the meat of the weasel is verboten, for “this animal conceives with its mouth.”67Lightfoot, J.B. The Epistle of Barnabas. Early Christian Writings. https://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/barnabas-lightfoot.html

Continue Reading:

Footnotes

- 1Note: While most scholars currently hold the gospel known to us as Matthew to be the second-written gospel, I believe this is based on outmoded scholarship and faulty logic as explained here: https://www.alangarrow.com/synoptic-problem.html

- 2BeDuhn, J. (2013). The First New Testament: Marcion’s Scriptural Canon. Polebridge Press.

- 3Attridge, H.W. The Gospel of Luke: A Novel for Gentiles. PBS Frontline. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/religion/story/luke.html#:~:text=Luke%20was%20probably%20writing%20in,places%20like%20Ephesus%20or%20Smyrna.

- 4BeDuhn, J. (2013). The First New Testament: Marcion’s Scriptural Canon. Polebridge Press.

- 5BeDuhn, J. (2013). The First New Testament: Marcion’s Scriptural Canon. Polebridge Press.

- 6BeDuhn, J. (2013). The First New Testament: Marcion’s Scriptural Canon. Polebridge Press.

- 7Luke 4:28-30. The Bible. New International Version.

- 8BeDuhn, J. (2013). The First New Testament: Marcion’s Scriptural Canon. Polebridge Press.

- 9Luke 6:20-37. The Bible. New International Version.

- 10Didache. Early Christian Writings. https://www.earlychristianwritings.com/didache.html

- 11Mark 3:7-8. The Bible. New International Version.

- 12BeDuhn, J. (2013). The First New Testament: Marcion’s Scriptural Canon. Polebridge Press.

- 13Luke 7:6-9. The Bible. New International Version.

- 14Luke 4:27. The Bible. New International Version.

- 15Luke 17:11-19. The Bible. New International Version.

- 16BeDuhn, J. (2013). The First New Testament: Marcion’s Scriptural Canon. Polebridge Press.

- 17Mark 3:34-35. The Bible. New International Version.

- 18Luke 8:21. The Bible. New International Version.

- 19Luke 6:47-49. The Bible. New International Version.

- 20Stating: You know the commandments: “You shall not murder; You shall not commit adultery; You shall not steal; You shall not bear false witness; You shall not defraud; Honor your father and mother.” 20BeDuhn, J. (2013). The First New Testament: Marcion’s Scriptural Canon. Polebridge Press.

- 21BeDuhn, J. (2013). The First New Testament: Marcion’s Scriptural Canon. Polebridge Press.

- 22Luke 16:16. The Bible. New International Version.

- 23Mark 9:1. The Bible. New International Version.

- 24Mark 9:47. The Bible. New International Version.

- 25Luke 17:20-22. World English Bible.

- 26Luke 14:26. The Bible. New International Version.

- 27Luke 9:61-62. New English Translation.

- 28Luke 9:59-60. The Bible. New International Version.

- 29Luke 20:34-35. The Bible. New International Version.

- 30Heid, S. (2001). Celibacy in the Early Church: The Beginnings of Obligatory Continence for Clerics in East and West. Ignatius Press.

- 31The Interpreter’s Bible, Vol. 8. Abingdon Press.

- 32Luke 16:19-25. The Bible. New International Version.

- 33Eisenman, R.H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin.

- 34Luke 11:2-4. The Bible. New International Version.

- 35Luke 23:34. The Bible. New International Version.

- 36Luke 23:46. The Bible. New International Version.

- 37Luke 24:1-11. The Bible. New International Version.

- 38Luke 24:1-32. The Bible. New International Version.

- 39Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press.

- 40Luke 24:36-43. The Bible. New International Version.

- 41BeDuhn, J. (2013). The First New Testament: Marcion’s Scriptural Canon. Polebridge Press.

- 42Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

- 43Acts 25:23-27. The Bible. New International Version.

- 44Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

- 45Hopkins, K. & Beard, M. (2012). The Colosseum. Harvard University Press.

- 46Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars. Life of Titus 7.

- 47Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars. Life of Titus 10.

- 48Barrett, A.A. (2009). Lives of the Caesars. John Wiley & Sons.

- 49Suetonius. The Lives of Twelve Caesars. Life of Domitian 2.

- 50Gowing, Alain M. (1992). Review: The Emperor Domitian. Bryn Mawr Classical Review.

- 51Jones, B. (2002.) The Emperor Domitian. Routledge.

- 52Ranke-Heinemann, U. (1990). Eunuchs for the Kingdom of Heaven: Women, Sexuality, and the Catholic Church. Translated by Heinegg, Peter. Doubleday

- 53Epictetus & Rolleston, T.W.H. The Teaching of Epictetus: Being the Encheiridion of Epictetus with Selections from the Dissertations and Fragments. Library of Alexandria.

- 54Josephus. Antiquities, Book XX, chapter 11.

- 55Louis Feldman. (1998). Josephus’ Interpretation of the Bible. University of California.

- 56Jones, B. (2002.) The Emperor Domitian. Routledge.

- 57Tacitus. Annals. xv. 55.

- 58Cassius Dio. Roman History lxvii. 14.

- 59Grainger, J.D. Nerva and the Roman Succession Crisis of AD 96-99. Routledge.

- 60Richardson, P. & Shukster, M.B. (1983). Barnabas, Nerva, and the Yavnean Rabbis. The Journal of Theological Studies, Volume 34, Issue 1. https://doi.org/10.1093/jts/34.1.31

- 61Galatians 2:9. The Bible. New International Version.

- 62Lightfoot, J.B. The Epistle of Barnabas. Early Christian Writings. https://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/barnabas-lightfoot.html

- 63NOTE: It’s also possible that this phrase was simply a well known cliche the author expected his audience to be familiar with.

- 64Lightfoot, J.B. The Epistle of Barnabas. Early Christian Writings. https://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/barnabas-lightfoot.html

- 65Lightfoot, J.B. The Epistle of Barnabas. Early Christian Writings. https://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/barnabas-lightfoot.html

- 66Lightfoot, J.B. The Epistle of Barnabas. Early Christian Writings. https://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/barnabas-lightfoot.html

- 67Lightfoot, J.B. The Epistle of Barnabas. Early Christian Writings. https://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/barnabas-lightfoot.html