Chapter 26

Christianity Entrenched

A Fractured Empire

Already weakened by invaders, plague, assassinations, and infighting, the Roman Empire faced another blow in 260 CE, when, in a tremendous defeat at Edessa in Syria, the Sassanid Persian Empire captured the Roman Emperor Valerian in battle, keeping him prisoner until his death. It was the first time Rome had faced this particular humiliation, and it was devastating to public morale. In the wake of this crisis, the empire faltered and fractured.1Brill’s Companion to Military Defeat in Ancient Mediterranean Society. (2018). Brill.

In the west, the provinces of Gaul, Britain, and Hispania broke away to form the Gallic Empire under the rule of a German tribesman who had joined the Roman legions. Meanwhile in the east, Queen Zenobia of Palmyra in Syria revolted against Rome, and in a series of swift military victories established her own empire encompassing the provinces of Syria, Egypt, Palestine, and half of Asia Minor. The Roman Empire proper was consequently reduced to Italy, Greece, north Africa, and half of Asia Minor.2“Rome’s Imperial Crisis of the Third Century”. Brewminate: A Bold Blend of News and Ideas. https://brewminate.com/romes-imperial-crisis-of-the-third-century/

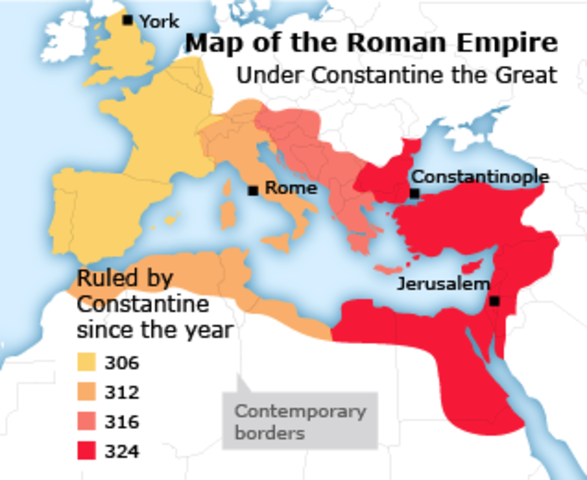

From 270 to 275 CE, however, the talented military tactician and new Roman emperor Aurelian secured the northern border of Italy from tribal invaders, then quickly set about reconquering the lands of the Palmyrene and Gallic upstarts, restoring the empire to its former size, and keeping the Sassanid Persians at bay in the east.3Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2024, February 14). Aurelian. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Aurelian But with the same pressures facing Aurelian’s successors, the unity did not last. In 286 CE, emperor Diocletian considered the sprawling Roman realm too unwieldy for a single ruler, and appointed his friend Maximian to govern the western half of the empire while he retained rule in the east. This scheme was further modified in 293 CE, with each half of the empire divided again into north-south regions so that four co-rulers governed.4Rees, R. (2004). Diocletian and the Tetrarchy. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Constantine’s Birth and Early Career

At this time there was a Roman military leader from Dacia (in the Balkan region of what is today Bulgaria) named Constantius5From Roman to Merovingian Gaul: A Reader. (1999). University of Toronto Press. who had been a leader in Aurelian’s successful campaign against the Empress Zenobia.6Potter, D. S. (2004). The Roman Empire at Bay: AD 180-395. Routledge. During his time in the east, he began a relationship with a woman of humble background named Helena from the region of Bithynia in northern Asia Minor.7Drijvers, J. W. (1992). Helena Augusta : the mother of Constantine the Great and the legend of her finding of the true cross. E.J. Brill. This is one of the few areas of the empire that may have, by this point, had a majority Christian population, though it is unlikely that Helena herself was a convert at this time. When Helena gave birth to a son, he was given the name Constantine in his father’s honor. But 17 years later when Constantius was elevated to the position of co-emperor of the west in 293 CE, he found it politically expedient to marry the daughter of the emperor in Rome, and so had Helena dismissed from his court and sent away.8Potter, D. S. (2004). The Roman Empire at Bay: AD 180-395. Routledge.

In 303 CE, in another attempt to promote Roman religious unity, the four emperors agreed to enact a second—and what would become the final—empire-wide persecution of all aberrant religions, falling hardest on the growing Christian minority population.9Lane Fox, R. (2006). Pagans and Christians: In the Mediterranean World from the Second Century AD to the Conversion of Constantine. Penguin Adult. And so for the second time in 50 years, the devotees of Jesus were forced on pain of imprisonment or execution to sacrifice to the Roman gods. In some areas, churches were burned and Christians removed from political offices.10Barnes, T. D. (1981). Constantine and Eusebius. United Kingdom: Harvard University Press. But enforcement of the new laws varied widely in the four quarters of the realm, with Emperor Constantius in Rome notably lax in his punishments, having formed political alliances with local bishops.11Potter, D. S. (2004). The Roman Empire at Bay: AD 180-395. Routledge.

Four-way shared governance of the far-flung empire lasted only through the first decade of the 300s CE. At that time, Constantius in the west, having subdued the various Germanic tribes as far as the Rhine river, was in the midst of a military campaign to the north of Britain, attacking the Picts who lived beyond Hadrian’s Wall in what is today Scotland, and was joined in this venture by his now 33-year-old son Constantine. While wintering with his army in the city of York in 306 CE, however, Constantius took ill and, just before his death, named his son as his successor.12Potter, D. S. (2004). The Roman Empire at Bay: AD 180-395. Routledge. Constantine remained in Britain to complete the campaign, and grew stronger and more popular as he moved back to the continent to continue attacking the Germanic tribes his father had fought before him.13Farr, E. (1873). The national history of England. United Kingdom.

Constantine’s succession was not universally recognized among the tetrarchy, and the balance of power between the four co-rulers became destabilized. Hoping to keep peaceful relations with Constantine, Emperor Maximian successfully arranged to have his daughter Fausta marry the new ruler.14Barnes, T. D. (1981). Constantine and Eusebius. United Kingdom: Harvard University Press.

Despite this, relations between the two co-rulers swiftly soured, forcing the 60-year-old Maximian to flee to Massilia (Marseille, France) where he was then captured in 310 CE, and forced by Constantine to commit suicide. A quarter of Constantine’s army then crossed the Alps into northern Italy in 312 CE, directly threatening to seize control of the city of Rome. Seeking justice against his father’s killer, Maximian’s son Maxentius declared war on Constantine, and brought an army loyal to his father to meet the invader at the Tiber River where the two factions fought the famous Battle of the Milvian Bridge.15Barnes, T. D. (1981). Constantine and Eusebius. Harvard University Press.

Two early accounts written by Christian authors make no mention of Constantine having experienced a religious vision on the eve of battle. But a later account by Eusebius, the Roman Catholic bishop of Caesarea in Palestine during these years—whose reliability as a historian has been questioned in modern times16Eisenman, R. H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. United Kingdom: Penguin Publishing Group.—claims to have heard directly from the emperor on the matter.17Bardill, J. (2012). Constantine, Divine Emperor of the Christian Golden Age. Cambridge University Press.

In this later account, it is said that while marching with his army, Constantine looked at the sun in the sky and saw the words in hoc signo vinces (“with this sign, you shall conquer”). The following night, the emperor is said to have had a dream in which Jesus showed him a symbol of the first two letters of the word “Christ” in Greek (a P and an X) transposed into what has become known as the Chi-Rho. Another Christian author of the time named Lactantius makes the additional claim that, having seen this Chi-Rho symbol in a dream the night before the battle, Constantine ordered his army to paint it on their shields.18Barnes, T. D. (1981). Constantine and Eusebius. Harvard University Press. (The standard cross that is now by far the most ubiquitous symbol of the Christian faith was not yet in use as a popular Christian symbol up to this time period.)19Stranger, J. (2007). “Archeological evidence of Jewish believers?”. In Skarsaune, O. (ed.). Jewish Believers in Jesus The Early Centuries. Baker Academic.

The battle itself was brief and decisive. Maxentius and his soldiers were forced into a retreat across the damaged bridge where he and many of his men were driven into the river and drowned.20Nixon, C. E. V., Rodgers, B. S. (1994). In Praise of Later Roman Emperors: The Panegyrici Latini. United Kingdom: University of California Press. His corpse was then fished out of the water, and Constantine ordered Maxentius’s head to be cut off and paraded through Rome.21Odahl, C. (2003). Constantine and the Christian Empire. Taylor & Francis.

If the accounts of Constantine’s vision of Jesus before the battle has any validity (and was not mere retrospective embellishment of history), it was still apparently not enough to actually convert him to the faith. But something had certainly shifted in Rome’s attitude toward the growing religion. In 313 CE, Constantine met with Licinius, the emperor in the east, and agreed to issue what was known as the Edict of Milan, granting full tolerance and full legal status to adherents of all faiths, including Christianity. This put an official end to any and all religious persecutions being carried out in any part of the empire.22Pohlsander, H. A. (2004). The Emperor Constantine. Routledge.

Constantine’s Reunification

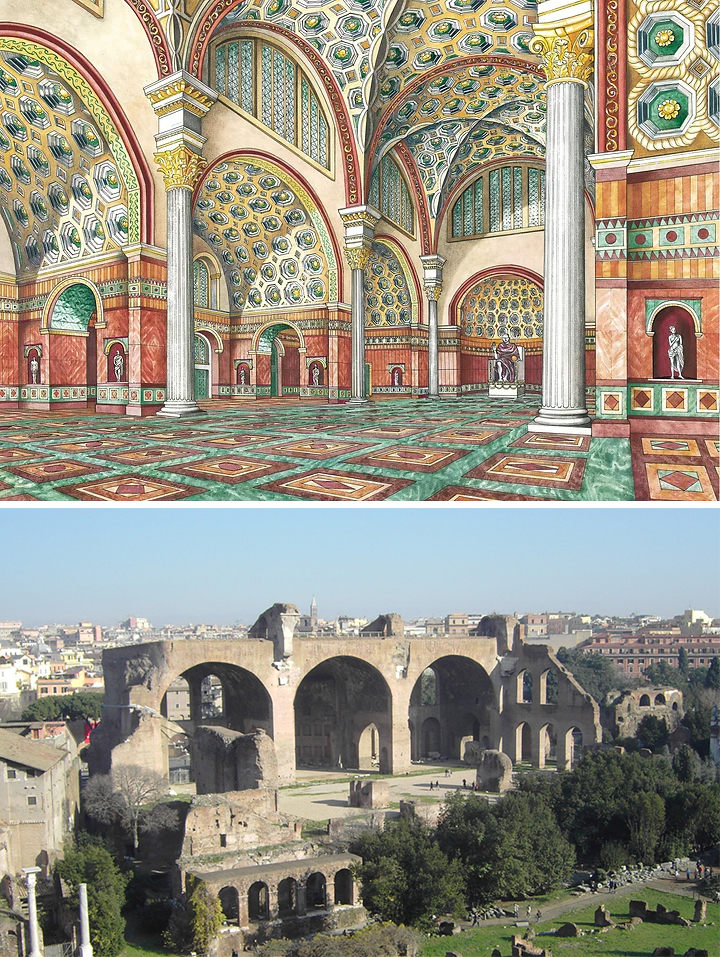

Ruling from Rome, Constantine established himself as a builder, making grand improvements to the Circus Maximus chariot racing stadium, allowing it to hold up to 150,000 spectators, possibly even 300,000 at most (historians’ estimates vary wildly)23Circus Maximus. UNRV Roman History. Pagan City and Christian Capital: Rome in the Fourth Century. (2002). OUP Oxford.—a number not remotely equaled until modern times. He completed two projects begun by his predecessor Maxentius: a Temple dedicated to Romulus, and a massive structure largely still standing near the Colosseum, known as the Basilica of Maxentius, in front of which was placed a great stone statue of Constantine holding the Chi-Rho symbol.24Pagan City and Christian Capital: Rome in the Fourth Century. (2002). OUP Oxford. The head, hand, and a single foot from this grand statue can be seen in Rome to this day.25Chandler, K. A. (2019). Constantine and the Divine Mind: The Imperial Quest for Primitive Monotheism. Wipf & Stock.

Relations between Constantine and the eastern emperor Lucinius deteriorated during the 310s CE. And when, in 320 CE, Lucinius sought to remove some Christians from political office and confiscate their property, Constantine accused him of reneging on the Edict of Milan, serving as an excuse to launch a civil war in 324 CE from which Constantine emerged the victor, and the first sole emperor of all the Roman provinces in 38 years.26Pohlsander, H. A. (2004). The Emperor Constantine. Routledge.

By this point, though he was supportive of Christians, Constantine’s primary focus of religious veneration seems to have been Sol Invictus,27Kee, A. (2016). Constantine Versus Christ. Wipf & Stock Publishers. the god first imported to Rome by the Empress Elagabalus and subsequently favored by Aurelian as well.28Halsberghe, G. (2015). The Cult of Sol Invictus. Brill. The still-today standing Arch of Constantine, built to commemorate his victories in reunifying the empire was conspicuously placed nearby the colossal statue of the sun god outside the Colosseum29Marlowe, E. (2006). Framing the Sun: The Arch of Constantine and the Roman Cityscape. The Art Bulletin, 223–242. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25067243—the one originally built as a depiction of Nero, but altered by Vespasian to depict Sol. Coins minted during Constantine’s reign up through 326 CE depict Sol Invictus,30Kee, A. (2016). Constantine Versus Christ. Wipf & Stock Publishers. and in 321 CE, the emperor decreed that the day named in the deity’s honor, Sunday, would henceforth be a day of rest. Whether this was enacted to benefit Christians, who had by this time chosen that day as their day of worship, is unclear.31Duffy, K. (2022). Christian Solar Symbolism and Jesus the Sun of Justice. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Late in his reign, there is evidence that Constantine may have attempted to merge the two faiths. In what is today Vatican City, the emperor financed the construction of the Basilica of Saint Peter in honor of the traditional founder of the Church of Rome.

Excavations of the basilica in the 1940s CE unearthed a fascinating mosaic that depicts Jesus in the guise of Sol Invictus. The latter god’s characteristic radiated crown worn here by Jesus would go on to be widely adopted by later Christian artists depicting the savior. And it is the December 25 festival of the sun god that was adopted as the anniversary celebration of Jesus’s birth32Brinkhof, T. (2023). Sol Invictus: The pagan Sun god that helped Christianity conquer the Roman Empire. Big Think. https://bigthink.com/the-past/sol-invictus/ beginning in 336 CE—though for another 50 years, churches in the eastern empire would favor a January 6 date for the holiday.33Bradshaw, Paul (2020). “The Dating of Christmas”. In Larsen, Timothy (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Christmas. Oxford University Press.

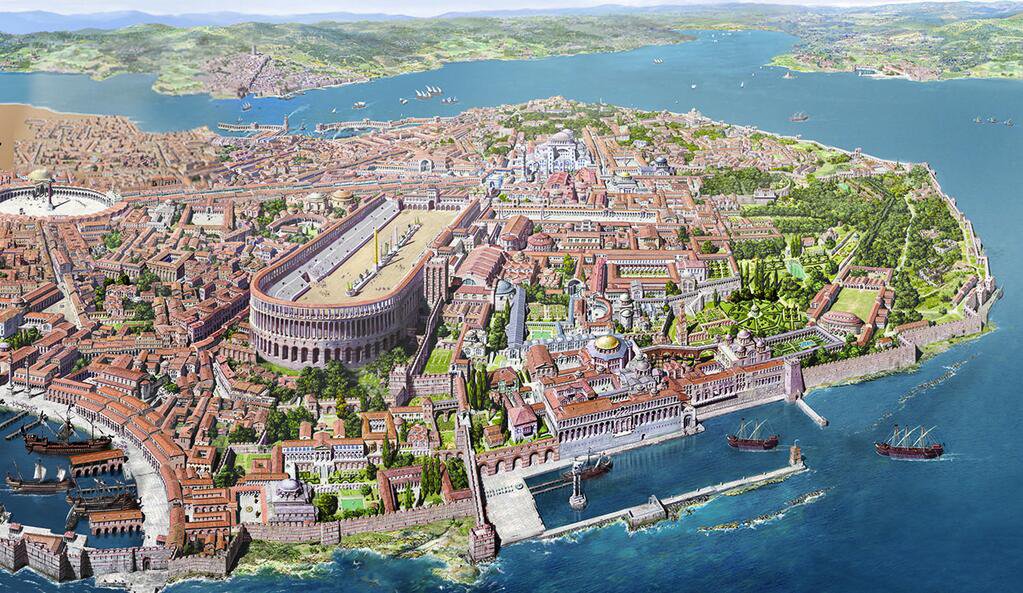

Over the course of the previous century, the cities of the eastern half of the Roman Empire had gained ascendancy over the west in terms of population and wealth.34Norwich, J.J. (1988). Byzantium: The Early Centuries. Penguin Books. Recognizing this, Constantine began considering several locations where he might construct a magnificent new capital for the empire, closer to its center of influence.35MacMullen, R. (2014). Constantine (Routledge Revivals). Taylor & Francis. He settled on the city of Byzantium, located at the strategically crucial and well-defensible site at the gateway from the Mediterranean to the Black Sea, at the point where the continents of Europe and Asia are separated by a strait of water only 2,000 feet wide, and through which passed many of the most lucrative trade routes in the empire.36The Oxford History of Byzantium. (2002). OUP Oxford.

When work on the new capital began, it was being referred to as New Rome, but upon its dedication was renamed after its founder as Constantinople (“City of Constantine”).37The Oxford History of Byzantium. (2002). OUP Oxford. There, among many great construction projects, was built the Church of the Holy Apostles on the site of a former Temple of Aphrodite.38Outhwaite, R. (2015). The Christian Temple: Aspects and Development. Xlibris UK.

In 326 CE, Constantine had his son Crispus and his wife Fausta murdered. The reasons for this have been obscured by the emperor’s subsequent attempt to utterly erase both of them from any historical records.39Odahl, C. (2010). Constantine and the Christian Empire. Taylor & Francis. Constantine’s mother Helena, however, was welcomed back to his imperial court and given a position of highest honor. Helena seems to have become a full convert to Christianity significantly earlier than her son, and her devotion to the religion was likely of great influence on his policies.40Mitchell, M.M., et al. (2006). Cambridge History of Christianity: Volume 1, Origins to Constantine. Cambridge University Press.

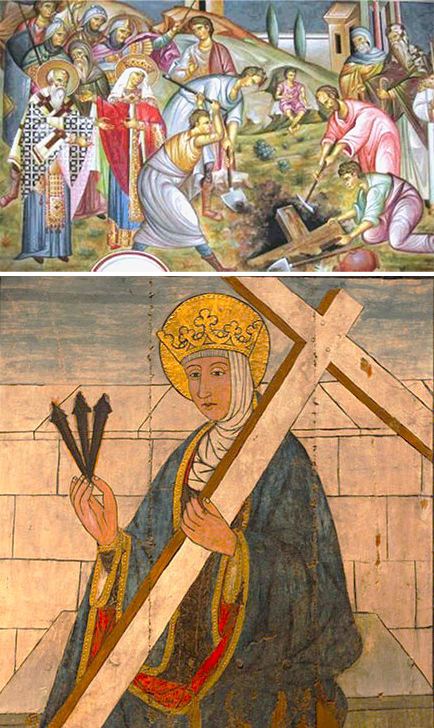

Soon after having his wife and son murdered, Constantine gave his mother unlimited access to the imperial treasury to fund her pilgrimage to Palestine. There she inaugurated the building of the Church of the Nativity at the supposed birthplace of Jesus, and the Church of the Holy Sepulcher—built on the site claimed to be Golgotha where the savior was crucified.41Norwich, J. J. (1997). A Short History of Byzantium. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. As Christian enthusiasm for holy relics developed in the coming centuries, Helena was retrospectively credited with having discovered such items as wood from the cross on which Jesus was executed, the nails that were put through his hands and feet, the ropes used to bind him to the cross, and the tunic he wore at the time of his death.42Dando-Collins, S. Constantine at the Bridge. United Kingdom: Turner Publishing Company. After her own death, Helena was sainted by the Catholic Church, and became a relic herself, with a skull said to be hers kept on display in the Trier Cathedral in Germany.43Larson, F. (2014). Severed: A History of Heads Lost and Heads Found. United Kingdom: Granta Publications.

From Persecuted to Persecutors

While everyday Christian adherents seldom concerned themselves with such matters, the fractious disagreements between Roman Catholic theologians and bishops over minutiae concerning the nature of the godhead was reaching new levels of heated contention during the reign of Constantine. In Alexandria in Egypt, a man named Arian put forth a popular theology which held that God the Father and Jesus Christ could not be considered one and the same, and that Jesus the Son did not always exist but was begotten by God, putting Jesus in a clearly subordinate position. Meanwhile in Rome and other cities, there was a strong and growing trend to consider the Father and Son as co-eternal, both having always existed as co-equals—neither in a position of subordination to the other.44Berndt, G. M. (2016). Arianism: Roman Heresy and Barbarian Creed. Taylor & Francis.

Largely prompted by Constantine’s annoyance at these squabbling church patriarchs and his desire for uniformity in doctrine,45Reese, T. S. (1998). Inside the Vatican: The Politics and Organization of the Catholic Church. Harvard University Press. in 325 CE, the emperor convened a council which took place in the city of Nicaea in Bithynia in Asia Minor.46Forsyth-Vail, G. Arius the Heretic. Unitarian Universalist Association. https://www.uua.org/re/tapestry/adults/river/workshop2/arius This would establish a pattern for resolving future controversies within the Church, and later Christian emperors would adopt a similar behind-the-scenes but influential overseeing role played by Constantine. In this first convention, about 250 bishops from across the empire from Spain to Palestine attended,47Eusebius. Vita Constantini, iii. as well as bishops from churches in the Sassanid Persian empire, and a bishop representing the Goths in Germany as well.48Wegner, P. D. (2006). A Student’s Guide to Textual Criticism of the Bible: Its History, Methods and Results. InterVarsity Press.

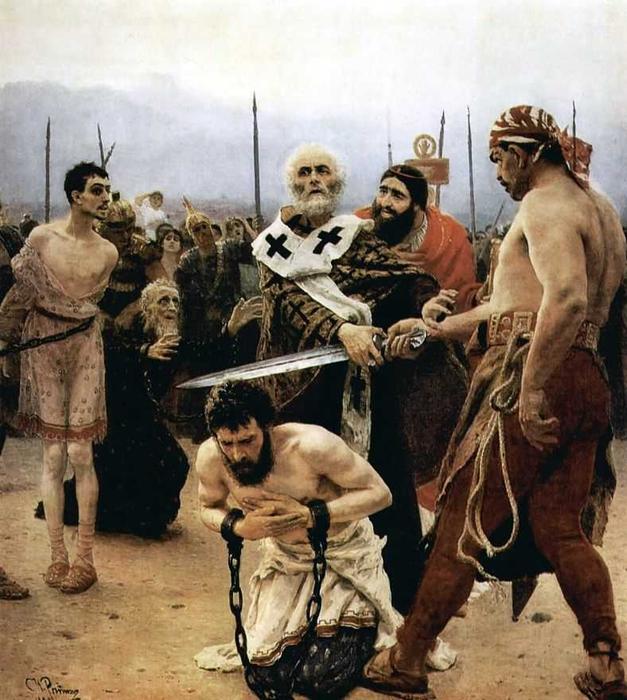

A month of fraught deliberations ensued. One perhaps legendary report included an incident in which Nicholas of Myra—around whom the legend of Santa Claus later developed—smacked the theologian Arian in the face.49Saint Nicholas the Wonderworker, Archbishop of Myra in Lycia. (2014). Orthodox Church in America. https://www.oca.org/saints/lives/2014/12/06/103484-saint-nicholas-the-wonderworker-archbishop-of-myra-in-lycia In the end, rather than work out an official statement of Church theology acceptable to all, the council ruled strongly against “Arianism”.50Ehrman, B. D. (2005). Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

They promulgated their newly agreed upon anti-Arian doctrine in what has become known as the Nicene Creed, still recited in many churches to this day.51Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Religion. (2010). Taylor & Francis. Its phrase describing Jesus Christ the Son of God being “of one substance” with God the Father was insisted upon by Constantine himself.52Hanson, R. P. C.. (2005). The Search for the Christian Doctrine of God: The Arian Controversy. T & T Clark. All those who refused to profess the creed were immediately excommunicated from the church, and Arianism became a persecuted “heresy”. Any and all writings by Arian were to be burned, and Arianism’s adherents were to be considered “enemies of Christianity”.53Lacelles, C. (2017). Pontifex Maximus: A Short History of the Popes. Crux Publishing Ltd. Other matters decided on by the council included:

- the standardization of the date of Easter54By this Sign: A.D. 250 to 350 : from the Decian Persecution to the Constantine Era. (2003). Christian History Project.

- a prohibition on the practices of money lending55Stapleford, J. E. (2009). Bulls, Bears and Golden Calves: Applying Christian Ethics to Economics. InterVarsity Press.

- a prohibition on self castration56Celibacy and Religious Traditions. (2007). Oxford University Press, USA.—apparently a common enough occurence to need addressing

- reconciliation with a sect known as the Novatianists57Stapleford, J. E. (2009). Bulls, Bears and Golden Calves: Applying Christian Ethics to Economics. InterVarsity Press.

- excommunication of a sect known as the Melitians58The Cambridge Companion to the Council of Nicaea. (2021). Cambridge University Press.

- and a prohibition on kneeling to pray on Sundays (standing during prayer remains the norm to this day among the Eastern churches)59Jackson, L. C. (2024). Holy Ground: The Importance of the Body, Posture, and Liturgy in Worship. Wipf and Stock Publishers.

Formation of the New Testament Canon

One issue not taken up by the Nicene Council was a formal declaration concerning which writings would be accepted into a closed canon of the Old and New Testaments. As early as 170 CE, an unknown author in Italy composed what is known as the Muratorian fragment—an early list of accepted Christian scriptures. Due to the document’s degradation, its first two gospels are unknown, but the gospels of Luke and John are listed as third and fourth. Its other accepted books are similar to what we are familiar with today, though notably absent are Hebrews, James, and 1 and 2 Peter, and one of the three epistles attributed to John. It also includes The Apocalypse of Peter and the Book of Wisdom—the latter of which was part of the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible used by the earliest Christians, but is not present in the Hebrew Bible as we know it today.60Hahneman, G. M. (1992). The Muratorian Fragment and the Development of the Canon. Clarendon Press.

During and shortly after the reign of Constantine, two of the earliest known New Testament collections were formed, though the details of who created them and where are debated by scholars, with guesses including Rome, Alexandria in Egypt, or Caesarea in Palestine. The earlier collection, known as the Codex Vaticanus (not for where it was composed, but for having been rediscovered in the 1400s CE in the Vatican Library), is notable for having not included the Revelation of John, as well as the epistles 1 and 2 Timothy, Titus, and Philemon. The latter composition, known as the Codex Sinaiticus, includes all the books from our present day New Testament, but also features the strongly anti-Jewish Epistle of Barnabas, and a long, highly allegorical writing known as The Shepherd of Hermas.61Sarna, N. M. , Davis, . H. Grady , Faherty, . Robert L. , Rylaarsdam, . J. Coert , Fredericksen, . Linwood , Stendahl, . Krister , Flusser, . David , Sander, . Emilie T. , Cain, . Seymour , Grant, . Robert M. and Bruce, . Frederick Fyvie (2024, February 9). biblical literature. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/biblical-literature This latter work is one which enjoyed great popularity in the early church despite espousing an adoptionist theology in which the Holy Spirit—here, oddly, identified as the Son of God—comes to dwell in Jesus as a reward for his having lived a wholly pure life.62Ehrman, B. D. (2005). Lost Scriptures: Books that Did Not Make It Into the New Testament. Oxford University Press, USA.

In the early 400s CE, a collection known as the Codex Alexandrinus, most likely formed in Egypt, is also very close to our current day New Testament. This canon leaves out The Epistle of Barnabas and The Shepherd of Hermas, but instead includes 1 and 2 Celement63Sarna, N. M. , Davis, . H. Grady , Faherty, . Robert L. , Rylaarsdam, . J. Coert , Fredericksen, . Linwood , Stendahl, . Krister , Flusser, . David , Sander, . Emilie T. , Cain, . Seymour , Grant, . Robert M. and Bruce, . Frederick Fyvie (2024, February 9). biblical literature. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/biblical-literature —with 1 Clement being, as we previously saw, an early epistle that portrayed Jesus as a heavenly high priest, and 2 Clement being a later forgery. Not until as late as 450 CE do we see a finalized uniform New Testament canon used across nearly all Roman Catholic churches.

Non-Catholic Christian churches, however, made their own choices about scripture. The Alogi church in Asia Minor rejected the validity of the Gospel of John and the Revelation of John, charging that they were written by the gnostic Cerinthus.64Havey, F. (1907). Alogi. In The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/01331b.htm The Syrian church composed is own New Testament using a single gospel that combined and harmonized Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John, and skipped 3 letters of Paul, and shunned the Revelation of John.65Hoover, R.W. (1993). How the Books of the New Testament Were Chosen. Biblical Archaeology Society. https://library.biblicalarchaeology.org/article/how-the-books-of-the-new-testament-were-chosen/ The Ethiopian church’s canon is notable for being the only Christian Bible to include several books in use by the Essenes and earliest Christians, including The Book of Watchers, the Enoch apocalypses, Jubilees, another Jewish Christian apocalypse called 2 Esdras, and three books of Meqabyan (Maccabees) that bear little resemblance to 1 and 2 Maccabees found in the apocrypha section of Catholic versions of the Old Testament. Some even more inclusive versions of the Ethiopic Bible also include The History of the Jews by Flavius Josephus.66The Bible. The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church Faith and Order. https://www.ethiopianorthodox.org/english/canonical/books.html

Julian the Reformer

It is only when Constantine fell gravely ill at age 65 that he officially, publicly adopted Christianity to the exclusion of other more traditional faiths.67Lane Fox, R. (1987). Pagans and Christians. Knopf. Even then, he waited until he was very near death to receive his baptism, believing that by postponing it for as long as possible, it would thereby maximize the number of his sins that were absolved.68Bowersock, G. W., Brown, P., Grabar, O. (1999). Late Antiquity: A Guide to the Postclassical World. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. Despite their having been dismissed as heretics at the Council of Nicea, Constantine chose an Arian bishop to perform his baptism (though Catholics would later paper over this embarrassment by falsely claiming the rite was presided over by Pope Sylvester I instead.69Canella, T. (2018). Sylvester I. Brill Encyclopedia of Early Christianity.) His death came just after Easter in 337 CE. In the wake of the emperor’s death, each of his three sons managed short reigns on the throne, but their costly civil wars for succession and constant infighting weakened them all, with Constantine II being killed in a failed invasion of Italy.

Again, despite the efforts at the Nicene Council to banish the sect, two of his sons adopted the “heresy” of Arianism.70Hall, C.A. How Arianism Almost Won. Christian History Institute. https://christianhistoryinstitute.org/magazine/article/how-arianism-almost-won While in power, they also pioneered the Christian persecution of rival faiths, banning on pain of death the traditional pagan sacrifices that had united Romans since the dawn of the Republic centuries before.71Kirsch, J. (2004). God Against the Gods: The History of the War Between Monotheism and Polytheism. Viking Compass. Pagan temples were forcibly shut down, and Christian mobs acting of their own volition pillaged and desecrated pagan monuments, shrines, and tombs.72Ammianus Marcellinus. Res Gestae 22. Laws were also passed forbidding Jews from marrying Christian women and making it illegal for Christians to convert to Judaism.73Codex Theodosianus 16.

Meanwhile in the west, Constantine’s nephew Julian was the popular governor of Gaul with several successful military campaigns against the German tribes under his belt, earning him the loyalty of a significant portion of the Roman army. Dissatisfied with the rule of Constantius II, the legions stationed in the city of Paris proclaimed Julian their emperor. They then marched east with the intent of meeting the armies of Constantine’s son in what would surely have been yet another bloody and costly civil war. But—in what must have been interpreted by Julian’s followers as divine intervention—while marching west, Emperor Constantius suddenly became fatally ill, and just before dying, named his cousin Julian as his rightful heir.74Greenwood, D. N. (2021). Julian and Christianity: Revisiting the Constantinian Revolution. Cornell University Press.

Julian had been raised in a Christian environment,75Bowersock, G.W. (1978). Julian the Apostate. Duckworth. but rejected the faith at age 20, and now as emperor he made strong efforts as a reformer, reestablishing traditional Roman worship in all its forms.76Teitler, H. C. (2017). The Last Pagan Emperor: Julian the Apostate and the War Against Christianity. Oxford University Press. His Tolerance Edict of 362 CE reopened pagan temples and returned to them all previously confiscated money and properties. Though he himself was partial to Sol Invictis, Julian supported the worship of all the pagan gods of his ancestors.77Smith, R. B. E. (2013). Julian’s Gods: Religion and Philosophy in the Thought and Action of Julian the Apostate. Taylor & Francis. He also joined one of the oldest salvation religions of the empire, the Eleusinian Mysteries, which he also attempted to restore and repopularize.78Athanassiadi, P. (2014). Julian (Routledge Revivals): An Intellectual Biography. Taylor & Francis. Despite this pronounced shift in religious priorities, Julian did not take actions to outlaw or persecute Christians, only removing Christian literature from schools.79Brown, P. (1989). The World of Late Antiquity: AD 150-750. Norton.

Julian’s greatest focus after becoming ruler, however, was to root out the vast networks of corruption that had solidified under Constantine and his sons, needlessly costing the state great sums of money, and slowing bureaucracy to a stand still. In a policy that set him apart from all preceding emperors, Julian considered himself on an equal social level to all his subjects, to the point of scandalizing the nobility and shocking everyday citizens with his informality toward them. On a trip to Antioch in Syria, Julian was angered to discover that greedy rich merchants were hoarding grain and price gouging the starving populace.80Bowersock, G. W., Brown, P., Grabar, O. (1999). Late Antiquity: A Guide to the Postclassical World. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. After these merchants failed to heed Julian’s suggestions to alter their cruel policies, he took direct control by capping prices, forcing the merchants to sell, and importing additional grain supplies from Egypt.81Libanius. Orations. 18.

Wishing to be a patron to the Jews as well, in 363 CE, Julian ordered work to begin on the rebuilding of the Temple of Jerusalem, destroyed by Rome 293 years before. Though he appropriated a huge sum of money to complete this project, it did not get past work on the foundations.82Neusner, J. (2008). Judaism and Christianity in the Age of Constantine: History, Messiah, Israel, and the Initial Confrontation. University of Chicago Press. (2008). Judaism and Christianity in the Age of Constantine: History, Messiah, Israel, and the Initial Confrontation. University of Chicago Press. The reasons for this are not entirely clear, but may have been the result of Christian sabotage efforts or accidental fire.83Gibbon, E., The Decline And Fall Of The Roman Empire. The Modern Library. Later Christians would claim an earthquake sent by God halted the project.84Neusner, J. (2008). Judaism and Christianity in the Age of Constantine: History, Messiah, Israel, and the Initial Confrontation. University of Chicago Press. (2008). Judaism and Christianity in the Age of Constantine: History, Messiah, Israel, and the Initial Confrontation. University of Chicago Press.

During the reign of Julian’s predecessor, the Sassanid Persians had repeatedly made raids across their shared border with the empire, but Constantius II died before a punitive campaign could be mounted.85Hunt, D. (1998). “The successors of Constantine + Julian”. In Averil Cameron & Peter Garnsey (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History XIII: The Late Empire, A.D. 337–425. Cambridge University Press. Such a task fell to Julian whose hope was to attack the Sassanids with the intent of forcing a regime change, replacing Shapur II with a more pliable ruler.86Potter, D.S. (2004). The Roman Empire at Bay: AD 180–395. Routledge. But the Roman army’s siege of the Sassanid capital was unsuccessful,87Goldsworthy, A. K. (2009). How Rome Fell: Death of a Superpower. United States: Yale University Press. and the guerilla-style Persian attacks during the army’s retreat dealt Julian a fatal blow.88Lascaratos, J. & Voros, D. (2000). Fatal Wounding of the Byzantine Emperor Julian the Apostate (361–363 A.D.): Approach to the Contribution of Ancient Surgery. World Journal of Surgery. Later Christian legend claimed that the “apostate” emperor was righteously murdered by a Christian traveling with him—a figure named Mercurius who was later sainted by the Church for this supposed action.89Sozomenus. Historia Ecclesiastica. 6.

Christianity Becomes Entrenched

Julian was the last non-Christian Roman emperor. He was succeeded by one of his bodyguards, Jovian who was immediately prevailed upon by an assembly of bishops imploring him to undo all of Julian’s religious policies.90Frend, W.H.C. (2003). The Early Church: From the Beginnings to 461. SCM Press. This he did, establishing Christianity as the state religion. Soon the Chi-Rho symbol was returned to the shields of a Roman army that would now conquer in the name of the emperor and Jesus Christ.91Vasiliev, A. A. (1958). History of the Byzantine Empire, 324–1453, Volume I. University of Wisconsin Press. It must be noted that, for all of Jesus’s ethical maxims in the New Testament promoting pacifism in the face of aggression, treating one’s enemies with love, and giving all one’s money to the poor, such seemingly core aspects of the savior’s teachings produced no seismic change in the behavior of any Christian emperor compared to the pagan ancestors who preceded them. Wars were still fought, personal enemies still murdered, and dissenters forcibly silenced.

Once firmly established at the highest levels of government, the Roman Catholic Church began in earnest their persecution of other branches of Christianity, as well as pagans, and all other faiths, implementing policies of violent intolerance. In 381 CE, with Christians still a minority population of the realm, Emperor Theodosius ended all pagan holidays and maintained his predecessor’s bans on divination, animal sacrifices and communal feasts, and apostasy from Christianity.92Graf, F. (2014). Laying Down the Law in Ferragosto: The Roman Visit of Theodosius in Summer 389. Journal of Early Christian Studies 22(2), 219-242. https://doi.org/10.1353/earl.2014.0022. In a move toward unabashed theocracy, bishop Ambrose of Milan had the emperor himself excommunicated, then deigned to dictate the terms of his return to the fold.93Liebeschuetz, John Hugo Wolfgang Gideon; Hill, Carole; Mediolanensis, Ambrosius (2005). Ambrose of Milan: Political Letters and Speeches (illustrated, reprint ed.). Liverpool University Press.

By 392 CE, Theodosius had declared a war on paganism, outlawing all its practices,94McLynn, N. B. (2014). Ambrose of Milan: Church and Court in a Christian Capital. University of California Press. and destroying many temples throughout the empire, including the massive Temple of Serapis in Alexandria95Brown, P. (1998). Late Antiquity. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. where Vespasian had officially been made emperor. In Edessa, the pagan philosopher Libanius pleaded with the emperor for toleration as Christian monks armed with stones and iron rods demolished statues, altars, and shrines throughout the cities and countryside, but he received no help.96Brown, P. (1992). Power and Persuasion in Late Antiquity: Towards a Christian Empire. University of Wisconsin Press. Christian mobs targeted the famous Temple at Delphi, leaving it in ruins, and desecrated the holy sites of the Eleusinian Mysteries.97Athanassiadi, Polymnia (1993). “Dreams, Theurgy and Freelance Divination: The Testimony of Iamblichus”. The Journal of Roman Studies. 83. doi:10.2307/300982

In Egypt, when pagans demanded the return of sacred items stolen from their temple, a Christian monk denied any wrongdoing, saying that their gods had been “peacefully removed” and added that “there is no such thing as robbery for those who truly possess Christ.”98Isbouts, J. (2014). The Story of Christianity: A Chronicle of Christian Civilization from Ancient Rome to Today. United States: National Geographic.

Heavily targeted as well were the two other fastest-spreading religions in the empire: Mithraism and Manichaeism. Mithraic temples were now desecrated or destroyed. A law was passed to financially cripple Manichaeans, forbidding them from making or being the beneficiary of any wills, and those found practicing their religion were stripped of their citizenship.99Lieu, S. N. C. (1985). Manichaeism in the later Roman Empire and medieval China: a historical survey. Manchester University Press.

Church elders composed several polemical writings denouncing Mani as a false prophet, and by the 400s CE, the religion’s leaders were being executed.100Lieu, S. N. C. (1985). Manichaeism in the later Roman Empire and medieval China: a historical survey. Manchester University Press. All of these persecutions eventually managed to quash all other competing religions in the Empire by the time of its ultimate collapse. But missionary work had already converted the leaders of many of the Germanic tribes, so it was Christian “barbarians” who first sacked Rome in 410 CE, then conquered the western half of the empire in 476 CE.101Fletcher, R. A. (1999). The Barbarian Conversion: From Paganism to Christianity. United Kingdom: University of California Press. In the east, meanwhile, Roman rule continued under the guise of the Byzantine Empire for another 1,000 years until it was conquered and sacked by the Muslim Ottoman Turks.102Foster, Charles (22 September 2006). “The Conquest of Constantinople and the end of empire”. Contemporary Review.

After imperial persecution banished the followers of Mani from the empire, their religion survived for centuries in the Middle East, and—as previously noted—as far away as China. In a way that Roman Catholicism did not, the Manichaeans inherited from James the Just and Peter’s earliest Christianity the notion of being a Zadokite (“Righteous One”) through a lifetime of virtuous behavior. The most elevated followers of Mani were known as “Zaddiks”,103Burkitt, F. C. (1922). The Religion of the Manichees. The Journal of Religion, 2(3), 263–276. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1195142 and like their Essene and earliest Christian forebears, they taught followers to prefer poverty to riches, to give one’s money to the poor, to suppress sexual desire, to practice fasting, to live separated from the world, and to abstain from alcohol.104MacLennan, B. “Manichaeanism and Wolfram’s Parzival”. web.eecs.utk.edu.

While traveling the Middle East as a merchant, the eventual founder of Islam, Mohammed, is thought to have encountered communities of Manichaeans. The Quran mentions a people it refers to as the Sabians (“Bathers”, “Baptizers”), who, along with Jews and Christians, were to be respected as “People of the Book”. Mohammed would go on to adopt the same title by which Mani had once been hailed: the Seal of the Prophets. And Mohammed, like Mani, saw himself as the Paraclete promised by Jesus.105Eisenman, R. H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin Publishing Group.

Continue Reading:

Footnotes

- 1Brill’s Companion to Military Defeat in Ancient Mediterranean Society. (2018). Brill.

- 2“Rome’s Imperial Crisis of the Third Century”. Brewminate: A Bold Blend of News and Ideas. https://brewminate.com/romes-imperial-crisis-of-the-third-century/

- 3Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2024, February 14). Aurelian. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Aurelian

- 4Rees, R. (2004). Diocletian and the Tetrarchy. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- 5From Roman to Merovingian Gaul: A Reader. (1999). University of Toronto Press.

- 6Potter, D. S. (2004). The Roman Empire at Bay: AD 180-395. Routledge.

- 7Drijvers, J. W. (1992). Helena Augusta : the mother of Constantine the Great and the legend of her finding of the true cross. E.J. Brill.

- 8Potter, D. S. (2004). The Roman Empire at Bay: AD 180-395. Routledge.

- 9Lane Fox, R. (2006). Pagans and Christians: In the Mediterranean World from the Second Century AD to the Conversion of Constantine. Penguin Adult.

- 10Barnes, T. D. (1981). Constantine and Eusebius. United Kingdom: Harvard University Press.

- 11Potter, D. S. (2004). The Roman Empire at Bay: AD 180-395. Routledge.

- 12Potter, D. S. (2004). The Roman Empire at Bay: AD 180-395. Routledge.

- 13Farr, E. (1873). The national history of England. United Kingdom.

- 14Barnes, T. D. (1981). Constantine and Eusebius. United Kingdom: Harvard University Press.

- 15Barnes, T. D. (1981). Constantine and Eusebius. Harvard University Press.

- 16Eisenman, R. H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. United Kingdom: Penguin Publishing Group.

- 17Bardill, J. (2012). Constantine, Divine Emperor of the Christian Golden Age. Cambridge University Press.

- 18Barnes, T. D. (1981). Constantine and Eusebius. Harvard University Press.

- 19Stranger, J. (2007). “Archeological evidence of Jewish believers?”. In Skarsaune, O. (ed.). Jewish Believers in Jesus The Early Centuries. Baker Academic.

- 20Nixon, C. E. V., Rodgers, B. S. (1994). In Praise of Later Roman Emperors: The Panegyrici Latini. United Kingdom: University of California Press.

- 21Odahl, C. (2003). Constantine and the Christian Empire. Taylor & Francis.

- 22Pohlsander, H. A. (2004). The Emperor Constantine. Routledge.

- 23Circus Maximus. UNRV Roman History. Pagan City and Christian Capital: Rome in the Fourth Century. (2002). OUP Oxford.

- 24Pagan City and Christian Capital: Rome in the Fourth Century. (2002). OUP Oxford.

- 25Chandler, K. A. (2019). Constantine and the Divine Mind: The Imperial Quest for Primitive Monotheism. Wipf & Stock.

- 26Pohlsander, H. A. (2004). The Emperor Constantine. Routledge.

- 27Kee, A. (2016). Constantine Versus Christ. Wipf & Stock Publishers.

- 28Halsberghe, G. (2015). The Cult of Sol Invictus. Brill.

- 29Marlowe, E. (2006). Framing the Sun: The Arch of Constantine and the Roman Cityscape. The Art Bulletin, 223–242. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25067243

- 30Kee, A. (2016). Constantine Versus Christ. Wipf & Stock Publishers.

- 31Duffy, K. (2022). Christian Solar Symbolism and Jesus the Sun of Justice. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- 32Brinkhof, T. (2023). Sol Invictus: The pagan Sun god that helped Christianity conquer the Roman Empire. Big Think. https://bigthink.com/the-past/sol-invictus/

- 33Bradshaw, Paul (2020). “The Dating of Christmas”. In Larsen, Timothy (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Christmas. Oxford University Press.

- 34Norwich, J.J. (1988). Byzantium: The Early Centuries. Penguin Books.

- 35MacMullen, R. (2014). Constantine (Routledge Revivals). Taylor & Francis.

- 36The Oxford History of Byzantium. (2002). OUP Oxford.

- 37The Oxford History of Byzantium. (2002). OUP Oxford.

- 38Outhwaite, R. (2015). The Christian Temple: Aspects and Development. Xlibris UK.

- 39Odahl, C. (2010). Constantine and the Christian Empire. Taylor & Francis.

- 40Mitchell, M.M., et al. (2006). Cambridge History of Christianity: Volume 1, Origins to Constantine. Cambridge University Press.

- 41Norwich, J. J. (1997). A Short History of Byzantium. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

- 42Dando-Collins, S. Constantine at the Bridge. United Kingdom: Turner Publishing Company.

- 43Larson, F. (2014). Severed: A History of Heads Lost and Heads Found. United Kingdom: Granta Publications.

- 44Berndt, G. M. (2016). Arianism: Roman Heresy and Barbarian Creed. Taylor & Francis.

- 45Reese, T. S. (1998). Inside the Vatican: The Politics and Organization of the Catholic Church. Harvard University Press.

- 46Forsyth-Vail, G. Arius the Heretic. Unitarian Universalist Association. https://www.uua.org/re/tapestry/adults/river/workshop2/arius

- 47Eusebius. Vita Constantini, iii.

- 48Wegner, P. D. (2006). A Student’s Guide to Textual Criticism of the Bible: Its History, Methods and Results. InterVarsity Press.

- 49Saint Nicholas the Wonderworker, Archbishop of Myra in Lycia. (2014). Orthodox Church in America. https://www.oca.org/saints/lives/2014/12/06/103484-saint-nicholas-the-wonderworker-archbishop-of-myra-in-lycia

- 50Ehrman, B. D. (2005). Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

- 51Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Religion. (2010). Taylor & Francis.

- 52Hanson, R. P. C.. (2005). The Search for the Christian Doctrine of God: The Arian Controversy. T & T Clark.

- 53Lacelles, C. (2017). Pontifex Maximus: A Short History of the Popes. Crux Publishing Ltd.

- 54By this Sign: A.D. 250 to 350 : from the Decian Persecution to the Constantine Era. (2003). Christian History Project.

- 55Stapleford, J. E. (2009). Bulls, Bears and Golden Calves: Applying Christian Ethics to Economics. InterVarsity Press.

- 56Celibacy and Religious Traditions. (2007). Oxford University Press, USA.

- 57Stapleford, J. E. (2009). Bulls, Bears and Golden Calves: Applying Christian Ethics to Economics. InterVarsity Press.

- 58The Cambridge Companion to the Council of Nicaea. (2021). Cambridge University Press.

- 59Jackson, L. C. (2024). Holy Ground: The Importance of the Body, Posture, and Liturgy in Worship. Wipf and Stock Publishers.

- 60Hahneman, G. M. (1992). The Muratorian Fragment and the Development of the Canon. Clarendon Press.

- 61Sarna, N. M. , Davis, . H. Grady , Faherty, . Robert L. , Rylaarsdam, . J. Coert , Fredericksen, . Linwood , Stendahl, . Krister , Flusser, . David , Sander, . Emilie T. , Cain, . Seymour , Grant, . Robert M. and Bruce, . Frederick Fyvie (2024, February 9). biblical literature. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/biblical-literature

- 62Ehrman, B. D. (2005). Lost Scriptures: Books that Did Not Make It Into the New Testament. Oxford University Press, USA.

- 63Sarna, N. M. , Davis, . H. Grady , Faherty, . Robert L. , Rylaarsdam, . J. Coert , Fredericksen, . Linwood , Stendahl, . Krister , Flusser, . David , Sander, . Emilie T. , Cain, . Seymour , Grant, . Robert M. and Bruce, . Frederick Fyvie (2024, February 9). biblical literature. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/biblical-literature

- 64Havey, F. (1907). Alogi. In The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/01331b.htm

- 65Hoover, R.W. (1993). How the Books of the New Testament Were Chosen. Biblical Archaeology Society. https://library.biblicalarchaeology.org/article/how-the-books-of-the-new-testament-were-chosen/

- 66The Bible. The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church Faith and Order. https://www.ethiopianorthodox.org/english/canonical/books.html

- 67Lane Fox, R. (1987). Pagans and Christians. Knopf.

- 68Bowersock, G. W., Brown, P., Grabar, O. (1999). Late Antiquity: A Guide to the Postclassical World. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- 69Canella, T. (2018). Sylvester I. Brill Encyclopedia of Early Christianity.

- 70Hall, C.A. How Arianism Almost Won. Christian History Institute. https://christianhistoryinstitute.org/magazine/article/how-arianism-almost-won

- 71Kirsch, J. (2004). God Against the Gods: The History of the War Between Monotheism and Polytheism. Viking Compass.

- 72Ammianus Marcellinus. Res Gestae 22.

- 73Codex Theodosianus 16.

- 74Greenwood, D. N. (2021). Julian and Christianity: Revisiting the Constantinian Revolution. Cornell University Press.

- 75Bowersock, G.W. (1978). Julian the Apostate. Duckworth.

- 76Teitler, H. C. (2017). The Last Pagan Emperor: Julian the Apostate and the War Against Christianity. Oxford University Press.

- 77Smith, R. B. E. (2013). Julian’s Gods: Religion and Philosophy in the Thought and Action of Julian the Apostate. Taylor & Francis.

- 78Athanassiadi, P. (2014). Julian (Routledge Revivals): An Intellectual Biography. Taylor & Francis.

- 79Brown, P. (1989). The World of Late Antiquity: AD 150-750. Norton.

- 80Bowersock, G. W., Brown, P., Grabar, O. (1999). Late Antiquity: A Guide to the Postclassical World. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- 81Libanius. Orations. 18.

- 82Neusner, J. (2008). Judaism and Christianity in the Age of Constantine: History, Messiah, Israel, and the Initial Confrontation. University of Chicago Press. (2008). Judaism and Christianity in the Age of Constantine: History, Messiah, Israel, and the Initial Confrontation. University of Chicago Press.

- 83Gibbon, E., The Decline And Fall Of The Roman Empire. The Modern Library.

- 84Neusner, J. (2008). Judaism and Christianity in the Age of Constantine: History, Messiah, Israel, and the Initial Confrontation. University of Chicago Press. (2008). Judaism and Christianity in the Age of Constantine: History, Messiah, Israel, and the Initial Confrontation. University of Chicago Press.

- 85Hunt, D. (1998). “The successors of Constantine + Julian”. In Averil Cameron & Peter Garnsey (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History XIII: The Late Empire, A.D. 337–425. Cambridge University Press.

- 86Potter, D.S. (2004). The Roman Empire at Bay: AD 180–395. Routledge.

- 87Goldsworthy, A. K. (2009). How Rome Fell: Death of a Superpower. United States: Yale University Press.

- 88Lascaratos, J. & Voros, D. (2000). Fatal Wounding of the Byzantine Emperor Julian the Apostate (361–363 A.D.): Approach to the Contribution of Ancient Surgery. World Journal of Surgery.

- 89Sozomenus. Historia Ecclesiastica. 6.

- 90Frend, W.H.C. (2003). The Early Church: From the Beginnings to 461. SCM Press.

- 91Vasiliev, A. A. (1958). History of the Byzantine Empire, 324–1453, Volume I. University of Wisconsin Press.

- 92Graf, F. (2014). Laying Down the Law in Ferragosto: The Roman Visit of Theodosius in Summer 389. Journal of Early Christian Studies 22(2), 219-242. https://doi.org/10.1353/earl.2014.0022.

- 93Liebeschuetz, John Hugo Wolfgang Gideon; Hill, Carole; Mediolanensis, Ambrosius (2005). Ambrose of Milan: Political Letters and Speeches (illustrated, reprint ed.). Liverpool University Press.

- 94McLynn, N. B. (2014). Ambrose of Milan: Church and Court in a Christian Capital. University of California Press.

- 95Brown, P. (1998). Late Antiquity. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- 96Brown, P. (1992). Power and Persuasion in Late Antiquity: Towards a Christian Empire. University of Wisconsin Press.

- 97Athanassiadi, Polymnia (1993). “Dreams, Theurgy and Freelance Divination: The Testimony of Iamblichus”. The Journal of Roman Studies. 83. doi:10.2307/300982

- 98Isbouts, J. (2014). The Story of Christianity: A Chronicle of Christian Civilization from Ancient Rome to Today. United States: National Geographic.

- 99Lieu, S. N. C. (1985). Manichaeism in the later Roman Empire and medieval China: a historical survey. Manchester University Press.

- 100Lieu, S. N. C. (1985). Manichaeism in the later Roman Empire and medieval China: a historical survey. Manchester University Press.

- 101Fletcher, R. A. (1999). The Barbarian Conversion: From Paganism to Christianity. United Kingdom: University of California Press.

- 102Foster, Charles (22 September 2006). “The Conquest of Constantinople and the end of empire”. Contemporary Review.

- 103Burkitt, F. C. (1922). The Religion of the Manichees. The Journal of Religion, 2(3), 263–276. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1195142

- 104MacLennan, B. “Manichaeanism and Wolfram’s Parzival”. web.eecs.utk.edu.

- 105Eisenman, R. H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin Publishing Group.