Chapter 5

Roman Domination

Intervention

Meanwhile to the north in Syria, the legendary Roman general Pompey—fresh from conquering Asia Minor—was now bringing a swift end to the Seleucid Empire which had been greatly reduced in size after suffering the long series of invasions by the expanding Parthian Empire to its east. Informed of the fraternal civil war in Judah, Pompey sent a representative to the region, and both brothers fighting for the throne sent ambassadors requesting assistance against the other. Aristobulus’s offer of 20,000 pounds of gold beat out Hyrcanus’s offer, and accordingly Pompey ordered Hyrcanus and his army to leave Jerusalem, which he and his supports promptly did, abandoning the Holy Temple and departing from the city.1Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

Taking full advantage of this, Aristobulus ordered his forces to attack Hyrcanus’s retreating Arab army, crippling it in a sneak attack that killed thousands. Not long afterward, Pompey and his army in Syria moved south, setting up camp at the northern border of Judah. Hyrcanus rushed to visit him in person, again stating his right to the throne, disparaging his brother, and seeking his assistance. Aristobulus too traveled in person to the Roman camp dressed in his royal finery to make his case before Pompey. But at the last minute Aristobulus had a crisis of conscience.2Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers. Likely under the influence of his fanatical Zadokite supporters, he decided he was not willing to lower himself to begging for help from impure foreigners, and he left. This infuriated Pompey who chased Aristobulus down and then forced him on pain of death to issue royal orders for all his troops to abandon all Jewish fortresses. Seeing the writing on the wall, Aristobulus quickly fled to Jerusalem to prepare for war with the Romans.3Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

Determined not to let the Jews make any siege preparations, Pompey led his troops directly to Jerusalem. Aristobulus was terrified at the sight of the approaching Roman legions and rushed out to meet the general, offering him gold and the surrender of the city and himself if he would spare Jerusalem from destruction. But when Aristobulus soon afterwards returned to the city gates on his way to fetch the promised gold, his zealous Zadokite supporters refused to open the doors to him, and the Jewish king was held captive by Pompey.4Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

Inside the city, fights broke out between the supporters of Hyrcanus and Aristobulus which forced the latter to retreat to the Temple complex and raise the drawbridge separating it from the rest of the city by a deep ravine. These Zadokites vowed to defend the Temple to the death. The rest of the population, at the behest of the Pharisees, opened the city gates of Jerusalem to the invading Romans and offered them advice on how best to rout the Zadokites holed up in the fortified Temple area. The Pharisees knew Zadokites kept the commandment to respect the Sabbath very seriously. They would not fight on that day unless attacked first. So, at the Pharisees’ suggestion, the Romans ceased fighting on the Sabbath as well, but used that day to fill in the ravine, and construct bridges and siege engines without worry of being harassed by the usual barrage of arrows and missiles.5Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

On all other days, however, the Romans and Zadokites would fire and sling their ammunition over the Temple’s walls. Pompey was reportedly impressed on hearing that the Zadokite priests carried on their daily Temple rites, rituals, and duties while paying no heed to the constant rain of deadly projectiles. Finally, after three months, the Romans managed to collapse one of the Temple wall’s towers. Even as the Romans and Pharisees rushed inside with swords drawn, the Zadokites paid them no mind and calmly went about their holy practices as each was viciously cut down, one by one, with most of the priests being killed by their own countrymen. Others among the Zadokites leapt to their death from the Temple’s high walls, or barricaded themselves inside rooms and set them on fire, dying as martyrs rather than submitting to Rome.6Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

Pompey himself then entered the Temple, and with great curiosity, insisted on seeing its fabled inner sanctuary, the Holy of Holies, where only the high priest was allowed to enter once per year at Yom Kippur. He was surprised to find that descriptions he had heard had been accurate, and that the Jews had no statue of their god or other types of sacred idols. There were treasures there, to be sure, including the great menorah, a mountain of spices, and 20,000 lbs of gold. But Pompey left the Temple’s treasures untouched, and ordered that Hyrcanus be reinstated as king and high priest, that the Temple be cleansed, and its rituals immediately resumed. He stripped Judah of all the lands taken in conquest by the previous Maccabean leaders, and then embarked on a return march to Rome, taking Aristobulus and his family prisoner—though one of his sons named Alexander managed to escape en route.7Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

The End of the Maccabean Dynasty

Aristobulus’s escaped son Alexander was able to gather a considerable amount of supporters as he made his way back to Jerusalem and within a few years managed to retake the holy city in 57 BCE. The cohort of Romans stationed in the city remained neutral in what appeared to be a fight between Alexander and his uncle Hyrcanus. But when Alexander’s supporters began repairs on the Temple walls destroyed by Pompey, the cohort attempted to stop them, and Alexander’s forces slaughtered them all. Alexander then immediately began recruiting a larger army to withstand Rome’s certain reprisal.8Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

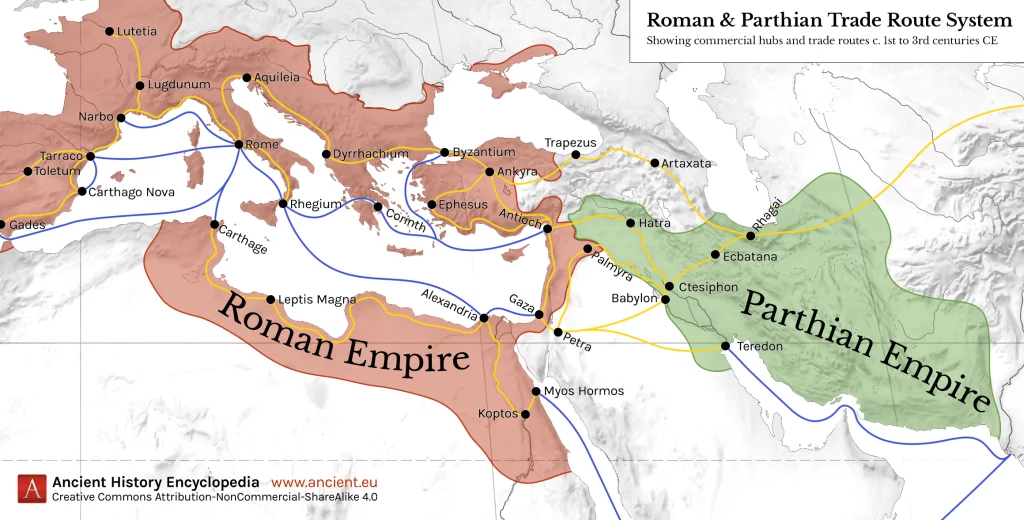

The leader of the Roman armies in Syria at this time was Aulus Gabinius who was planning an invasion of the Parthian Empire. The Parthians were Rome’s most powerful rival, and their borders had moved steadily westward toward the Mediterranean just as Rome’s borders moved eastward, and the two now controlled adjoining lands. But before such a massive campaign could start, the Jews in rebellion to the south would have to be dealt with. Gabinius and his lieutenant—the 26-year-old Mark Antony in his first military campaign—led their army south, and in a series of battles, took over Alexander’s strongholds throughout Judah, leaving him fleeing from one fortress to the next. His surrender was negotiated by his mother, the aged Queen Salome, who bargained for him to remain unharmed in Judah.9Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

Though Hyrcanus was again reinstated as high priest, the Romans ended the Judahite monarchy, which was never again to be reestablished. It was replaced by a form of aristocracy devised by Hyrcanus’s top advisor, an Idumaean nobleman named Antipater. Though certain important political functions would be retained by Hyrcanus, he was now demoted to the non-royal title of ethnarch (“leader of the people”). Since Hyrcanus had never actually desired the job of governing a nation, the more capable and eager Antipater took on these responsibilities, proving himself a very able administrator and tax collector, traits always favored by overseers in the Roman Republic.10Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

During these years, Antipater married an Arab noblewoman named Cypros, a relation of the king of Nabatea. They had five children who they raised as Jews, one of whom was a son they named Herod. Antipater won the appreciation of the Romans by continuously supplying their armies and even negotiating on their behalf to make peace with Nabateans. In an act of Maccabean family reconciliation, Alexander now married the daughter of his brother Hyrcanus, and they produced a son named Aristobulus III and a daughter named Miriam.11Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

Gabinius and his legions in Syria now prepared once more to invade Parthia, but were then ordered by Pompey to instead march to Alexandria in Egypt to restore order there by reinstating King Ptolemy XII who had been deposed. In Judah, Antipater enthusiastically prepared supplies for the Roman army and recruited his own contingent of Jewish soldiers that joined them on the campaign.12Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

With Antipater away and the Romans otherwise occupied, Alexander now began another insurrection. This time was different, however. Instead of going after his brother or the Pharisees, Alexander and his supporters targeted Romans, seeking them out across the lands of Judah, and showing no mercy. The fighting spilled over into neighboring Samaria, where the surviving Romans took shelter atop Mount Gerizim where they were besieged.13Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

On Antipater’s return, he managed to persuade many of the rebels to return to their homes before they would inevitably face the full might of Rome. This left only the true diehard rebels left in revolt—and yet this remaining fanatical army was still larger than any that Alexander’s father had ever led. But even so, they were no match for Roman legionaries of equal numbers and were decisively defeated with thousands killed. Continuing to honor the promise made to his mother, however, Gabinius did not execute or even exile Alexander.14Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

The First Triumvirate

A few years previous in 60 BCE, a secret agreement had been made which effectively split political control of the Roman Republic between three men: Pompey the great general of the east, Julius Caesar the great general who conquered Gaul (France) and Britain, and Marcus Crassus who led the army that defeated Spartacus’s slave revolt and who was reputed to be the richest man in the republic.15Holland, T. (2003). Rubicon: The Last Years of the Roman Republic. DoubleDay.

Crassus, seeking greater glory in military conquest, now took command of the Roman legions in Syria. He planned to do what Gabinius had not been able to: finally launch the invasion of Parthia. To finance this upcoming campaign, Crassus confiscated the 20,000 lbs of gold from the Jerusalem Temple’s treasury that Pompey had left untouched.16Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers. His Roman army did indeed invade Parthia, but their legions were caught off-guard by the extremely agile and deadly Parthian horse-mounted archers. Crassus watched his son die in battle before being overrun and killed himself.17Holland, T. (2003). Rubicon: The Last Years of the Roman Republic. DoubleDay.

He was replaced by his lieutenant Cassius Longinus who retreated to Antioch to secure it against a Parthian counter-invasion. At this point another revolt occurred in Judah. It was not led by any of the Maccabees, but by a military commander named Pitholaus who had fought under both Antipater and Aristobulus, and now attempted to rally the supporters of Alexander. His movement was swiftly and mercilessly crushed by the impatient Longinus, who then had thousands of Jewish rebel soldiers sold into slavery, and at Antipater’s advice, had Pitholaus executed.18Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

Relations between Caesar and Pompey quickly soured, and in 49 BCE, Caesar famously marched his legions across the Rubicon River from Gaul into Italy, effectively staking claim to Rome. Pompey and his forces retreated to the east to regroup.19Holland, T. (2003). Rubicon: The Last Years of the Roman Republic. DoubleDay. The would-be Jewish king Aristobulus, who was being held prisoner in Rome, was now released by Caesar, and ordered to stir up trouble against Pompey in Syria. But soon after his arrival, one of Pompey’s supporters managed to assassinate him with poison. Alexander may have traveled to Antioch to conspire with his father, or may have been arrested in Judah and brought there, but either way, Pompey was entirely unwilling to allow him to cause any more trouble in Judah. He was tried and found guilty of various offenses against the republic, and beheaded.20Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

Then in 47 BCE, Pompey’s forces were routed in battle by those of Caesar and his second-in-command Mark Antony. The defeated general sought refuge by sailing to the Ptolemaic kingdom of Egypt where the young Ptolemy XIII was in a struggle for power against his older sister Cleopatra. Alerted that Pompey was on his way, Ptolemy’s royal eunuch advisors counseled the boy to avoid provoking Caesar’s wrath by harboring his enemy. So Ptolemy had Pompey assassinated as soon as he landed at Alexandria. When Caesar arrived there three days later with his armies, he was presented with Pompey’s severed head. In a show of disgust and grief, he had the assassins executed. With all of his rivals removed though, Caesar’s power was entirely unchecked and he now effectively became an emperor in all but name. Aristobulus’s body, which had remained unburied but preserved in honey in Antioch, was later sent home to Jerusalem by Mark Antony.21Holland, T. (2003). Rubicon: The Last Years of the Roman Republic. DoubleDay.

Caesar Rewards Antipater

At Alexandria, Cleopatra convinced Caesar to take her side in the Egyptian civil war, and the two began a romantic relationship. Ptolemy and his advisors responded by secretly summoning their armies from across the land to besiege the city.22Holland, T. (2003). Rubicon: The Last Years of the Roman Republic. DoubleDay. With Caesar trapped, and fierce fighting underway—causing fires that nearly missed destroying the Great Library—a rescue mission was hatched by a nobleman named Mithridates from Pergamon in Asia Minor.

Antipater, who had taken Pompey’s side in the civil war, now deftly pivoted his loyalties. He eagerly volunteered to support Mithridates’s army with supplies, and raised a force of 3,000 Jews, personally leading them into battle. During the campaign, Antipater proved himself on multiple occasions. He was first to breach the city walls in one battle, successfully negotiated passage from hostile Egyptian Jews, saved the retreating Mithridates from certain death in another battle, and became wounded at one point, leaving him with permanent scars on his body.23Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

Once the rescue mission was complete, the Roman army defeated Ptolemy’s remaining forces at the Battle of the Nile. Caesar left Egypt with Cleopatra securely in power and also pregnant. She would give birth to his only natural son, at first named Pharaoh Caesar, but later known as Caesarion (“Little Caesar”). Although Cleopatra made repeated public claims to have birthed his heir, Caesar did not publicly recognize the child as his own. But traveling next to Syria, Caesar did publicly recognize and reward the heroic acts of Antipater that had been related to him by Mithridates.24Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

Antipater was granted Roman citizenship—among whose many benefits was freedom from taxation. He was also appointed procurator (“treasurer”) of Judah, and was given permission to rebuild the walls of Jerusalem—a project he immediately undertook. Hyrcanus was still nominally the head of the people of Judah, but Antipater was frustrated by his longtime boss’s apathy in his old age. Taking matters into his own hands, he appointed his eldest son Phasael as governor of Jerusalem and its surrounding areas, and made his younger son Herod governor of Galilee.25Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

The 25-year-old Herod immediately made a name for himself by chasing down, rooting out, and then executing a large and violent band of rebels operating out of caves in the highlands near the border with Syria, led by a man named Hezekias. This act earned him the praise of local Syrians who sang his praises for restoring peace; and it earned him the thanks and paternal friendship of the governor of Syria, Sextus Caesar, a relative of the newly-declared dictator-for-life in Rome.26Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

But the Jews were less thankful. Advisors to Hyrcanus argued that Herod had acted illegally in executing fellow Jews without his consent, and without bringing charges against them before the Sanhedrin (the Jewish high court). So Herod was called to Jerusalem to stand trial. Before the proceedings could finish, however, Hyrcanus was sent an order from Sextus to acquit Herod on all charges. Though it further upset the people, Hyrcanus acquiesced and pronounced him innocent. Sextus then immediately appointed Herod governor of Southern Syria and Samaria, taking him out of Judah, out of harm’s way, and giving him command of a significant army. Sextus himself, though, was then assassinated by one of Pompey’s devoted former followers. Antipater dutifully sent a Jewish force to assist the Roman armies as they fought to avenge the assassination of Sextus.27Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

Then in March of 44 BCE, a coalition of Roman senators with the stated intention of restoring the republic, assassinated Julius Caesar, igniting a bloody civil war. Mark Antony allied with Caesar’s nephew and chosen heir, the young Octavian Caesar. The senators’ faction was led by Cassius Longinus and Marcus Brutus. To raise the desperately needed funds to wage war, Longinus brought his army on a tour of Syria and surrounding cities, demanding their leaders pay tributes greater than any could actually afford. Nonetheless Herod was the first to contribute to the cause, offering 150,000 lbs of gold, and thereby switching his allegiance away from Caesar’s family to their enemy. Other cities of Judah were late with their payments, and an infuriated Longinus took captive the entire populations of Gophna, Emmaus, Lydda, and Thamna and sold them into slavery.28Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

Herod Secures Roman Favor

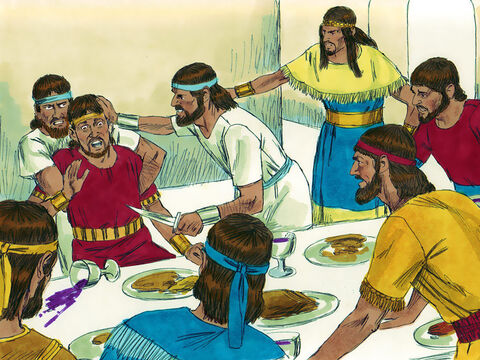

In 42 BCE, a local feud that had developed between Antipater and a nobleman Malichus—an ambitious army commander—turned deadly. At the end of a feast, Antipater collapsed and died, apparently having been poisoned. Accused of assassination, Malichos protested his innocence and made a show of grieving. Herod pretended to be taken in by his displays, but was merely biding his time. The high priest Hyrcanus may have secretly supported Malichus, wanting to be rid of Herod. But months later at another feast, Herod gave a signal to a group of soldiers who drew their swords and stabbed Malichus to death. Hyrcanus fainted at the sight, but did not openly condemn Herod’s actions, and now could do little to get out from under his domination.29Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

Herod won over some of the Jews after this with a string of military victories that retook some of the lands and fortresses in Galilee that had recently been captured by the Phoenicians. Though he had previously married a Jewish noblewoman named Doris, he now became engaged to marry the Maccabean princess Miriam as well, whose parents were Alexander and the daughter of Hyrcanus. A majority of the population, however, remained staunchly against Herod. Despite having been raised Jewish, he was regarded as a violent foreign overlord and a lackey of the Romans.30Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

The Roman civil war ended in victory for Caesar’s heirs. Cassius Longinus was defeated in battle by Mark Antony who took control of the eastern half of the republic and began a romantic relationship with Cleopatra while Caesar’s nephew Octavian established himself at Rome. Remembering his gratitude toward Antipater, Antony summoned his loyal friend’s sons to Egypt and formally recognized Herod and his brother Phasael as co-rulers of Judah. He also acquiesced to Herod’s request for the release of the Jews who had been sold into slavery by Longinus at the start of the war.31Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

A contingent of the Jewish nobility that had come to Alexandria in Egypt to protest against the elevation of Herod and his brother were then threatened with execution by the Romans and driven away. When Antony next traveled to the coastal Phoenecian city of Tyre he was met there by hundreds of ambassadors also protesting Herod and Phasael. Their actions were creating disorder in the city and verged on becoming a riot, so Antony ordered his guard to attack them, killing many, and wounding many more.32Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

Antigonus and the Parthians

In 39 BCE, the Parthian emperor’s son Pacorus led an invasion of the Roman republic, taking control of Syria as well as Tarsus in southeastern Asia Minor. As they considered their next move, another of Aristobulus’s sons who had escaped from captivity in Rome met Pacorus and formed a secret alliance. Antigonus Maccabee and his supporters marched into Judah from the north and were welcomed as liberators. At Passover, a great crowd of armed Jews entered Jerusalem and battles broke out throughout the city between Herod’s forces and those fighting for Antigonus. After much bloodshed, Antigonus craftily suggested that the seemingly neutral Parthians act as mediators to restore the peace. Phasael and Hyrcanus consented, but Herod sensed a trap.33Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

A meeting was arranged in Galilee. Herod’s brother and the high priest were welcomed with gifts and hospitality, but during their stay they overheard discussion of a deal Antigonus had made with the Parthians, offering them huge amounts of gold as well as hundreds of Jewish women as slaves. They further learned that the only reason the Parthians had waited to arrest them was to give their army time to attack Jerusalem. Herod and his supporters escaped by night to the safety of the fortress at Masada along the coast of the Dead Sea as the Parthians took Jerusalem, plundering it—though Herod had taken its greatest treasures with him. Pacorus’s forces then marched into Idumea where they destroyed Antipater’s hometown Marisa, and killed as many of Herod’s supporters there as they could find.34Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

Antigonus was hailed as king and high priest by his many supporters in Jerusalem, restoring the Maccabean royal line 18 years after the Romans had ended the monarchy. But the celebrations were more motivated by the removal of Herod than for the elevation of Antigonus who was not well known to the people. Phasael and Hyrcanus were brought to Antigonus in chains. The new king bit off his uncle’s ears, mutilating him so as to prevent him from ever again being eligible for the high priesthood under Jewish law. Herod’s brother Phasael denied Antigonus the satisfaction of torturing him by instead managing, with his hands still bound, to commit suicide by bashing his head against a rock.35Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

Continue Reading:

Footnotes

- 1Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

- 2Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

- 3Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

- 4Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

- 5Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

- 6Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

- 7Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

- 8Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

- 9Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

- 10Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

- 11Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

- 12Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

- 13Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

- 14Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

- 15Holland, T. (2003). Rubicon: The Last Years of the Roman Republic. DoubleDay.

- 16Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

- 17Holland, T. (2003). Rubicon: The Last Years of the Roman Republic. DoubleDay.

- 18Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

- 19Holland, T. (2003). Rubicon: The Last Years of the Roman Republic. DoubleDay.

- 20Grainger J.D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers.

- 21Holland, T. (2003). Rubicon: The Last Years of the Roman Republic. DoubleDay.

- 22Holland, T. (2003). Rubicon: The Last Years of the Roman Republic. DoubleDay.

- 23Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

- 24Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

- 25Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

- 26Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

- 27Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

- 28Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

- 29Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

- 30Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

- 31Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

- 32Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

- 33Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

- 34Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.

- 35Whiston, W. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Publications.