Chapter 15

The First Gospel

Lord Jesus Brought Down to Earth

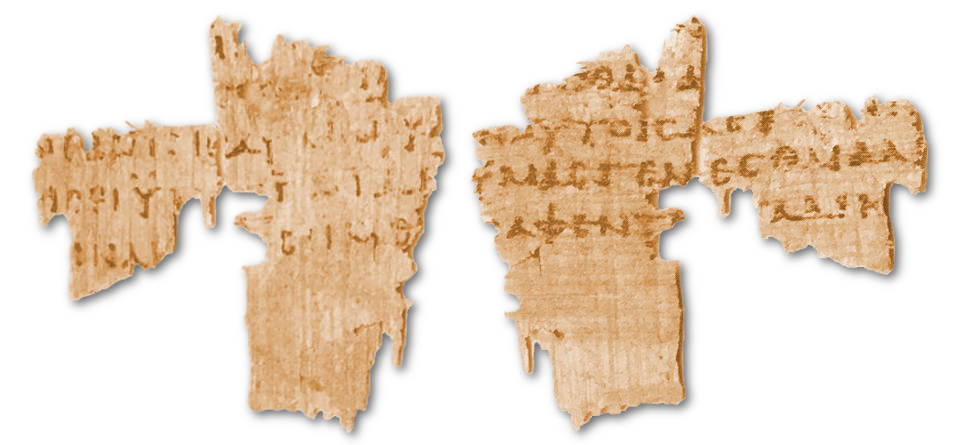

Few writings in the history of the world have had as much impact as the first gospel, originally simply titled The Gospel of Jesus Christ as its first line makes clear.1Mark 1:1. The Bible. New International Version. (It was published anonymously, as was often the case with religious writings of the time. The familiar but false attributions to Mark, Luke, Matthew, and John were adopted later in an attempt to tie each gospel to an early figure from Christian history.)2Ehrman, B. (2014). Why Are the Gospels Anonymous? The Bart Ehrman Blog. https://ehrmanblog.org/why-are-the-gospels-anonymous/ Most likely written in the 80s CE,3Note: Most secular scholars date the first gospel after 70 CE, but not long after. I have seen no compelling argument that it could not be as late as approximately 80 CE, as the only constraint is that it must have been published and disseminated before the second gospel which uses great amounts of material from it. it is the first known writing to present Jesus as having lived among humans on earth, and the first to attribute his crucifixion to earthly agents rather than Satan and his demons in the firmament.

The events are set about 50 years before the author’s time, in the era when the existence of Lord Jesus was first revealed in visions to the first apostles like Peter and James. It’s hard to be certain just what motivated the author to take the heavenly Son of God and mythologize him with a recent life on earth full of stupendous miracles and wonders.

Likely Motivations

One possible motivation that has been suggested is that the author’s writing wasn’t intended by him to be taken as a factual report of history, but rather as an allegory—a fable, or an extended parable meant to impart important lessons to its readers.4Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press. There is good evidence for this notion in the New Testament itself. The book of Hebrews speaks plainly of tiered levels of doctrinal teachings used among the earliest Christians. As in the salvation religions of the day, initiates are likened to infants “needing milk, not solid food.” The author goes on to explain that “solid food is for the mature, whose perceptions are trained by practice to discern both good and evil.” He urges his hearers to “progress beyond the elementary instructions about Christ.”5Hebrews 5:11-14. The Bible. New International Version. Likewise, Paul, in one of his letters clearly states that there is a teaching he can’t impart to his Corinthian readers because they are not of sufficient rank in the church. He too uses the particular terminology of the salvation religions, distinguishing “newborn babes” from the “perfected”. The truth that the perfected are taught, he explains, is a secret and “hidden in a mystery”.6Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press.

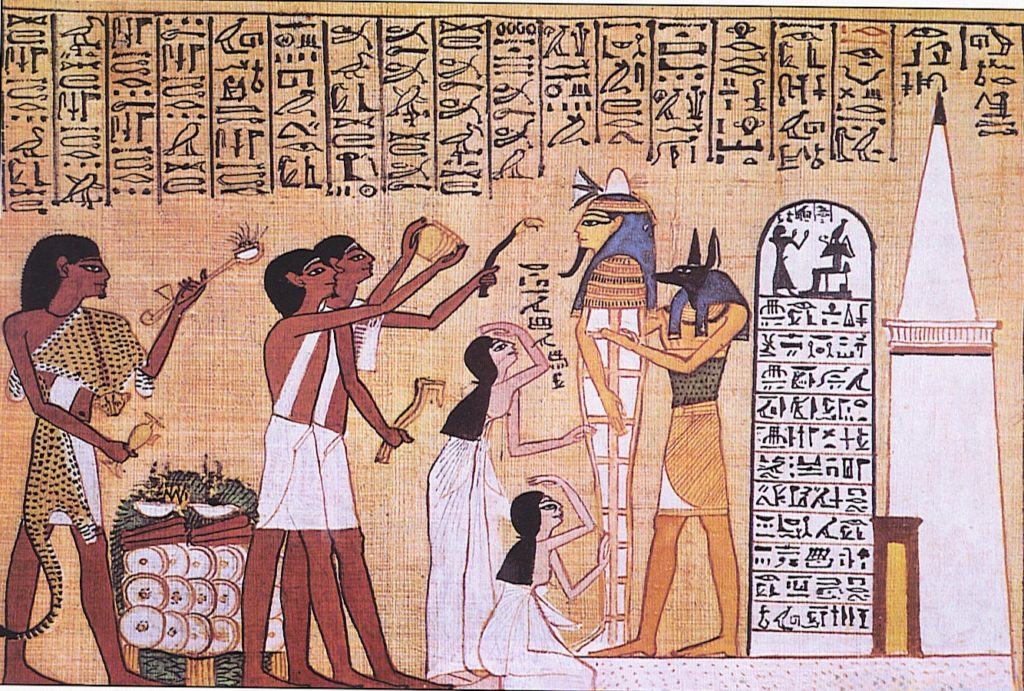

Consider also the contemporary fellow dying-and-rising Osiris, an ancient member of the traditional Egyptian pantheon. By the time of the advent of Christianity, Osiris had also been co-opted as the central figure of a Graeco-Roman salvation religion. (This fit a general pattern in which a foreign deity, like Mithra from Persia, was removed from its original religious context, imported into a new “mystery cult”, and molded to the needs of a new people7Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press.—a form of ancient cultural appropriation, we might say today. Even Christianity itself can easily be seen this way, with Paul and his followers taking the Jewish god and his heavenly messiah out of their original context and making them the focus of a new Graeco-Roman anti-Jewish salvation religion.)

Each of the dying-and-rising salvation religions’ gods had a particular public story (akin to a “gospel”) set in a particular point in history on earth. Each of these gods (often characterized as a “son of god”) underwent a “passion” in which they suffered and died, and each achieved a victory over death–a return to life that secured the eternal life of their followers.8Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press.

We don’t have details of the teachings of many of these religions, but because the famous ancient writer Plutarch was, for a time, a devotee of Osiris, we do have one surviving letter–written around the same time that the First Gospel was being penned–in which he candidly describes the faith. Osiris, we learn, was presented to initiates as a historical Pharaoh who lived a real life on earth, with named family members, who announced various teachings, and performed many exploits.9Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press.

Plutarch goes on to explain that, while this fabricated story is taught to initiates in the faith, those showing true devotion are eventually taught the higher-level teachings. To those ready for such revelations, it is explained that the story of Osiris living on earth is merely a myth. The actual Osiris, they learn, was killed by demons in the “firmament” between the sky and the moon. A startlingly familiar idea, as we have seen. And of course, no one today is arguing that Osiris was an historical figure.10Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press.

A later Christian patriarch named Clement of Alexandria would write that such a distinctly tiered system of teachings was a good and necessary practice. He even outright says that there is a secret understanding of the gospel that he is forbidden to tell his readers.11Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press. Even within the pages of the first gospel we find a scene in which disciples question Jesus in private about why he uses parables rather than straightforward teachings when speaking to crowds. Jesus responds, “The secret of the kingdom of God has been given to you. But to those on the outside everything is said in parables so that they may see and see but never perceive, hear and hear but never understand.”12Mark 4:10-12. The Bible. New International Version. So the first gospel may have been written as an allegory—specifically, an entry level doctrine for initiates to the faith.

If, on the other hand, the author of the first gospel did intend for his story of Jesus on earth to be taken as factual history, another possible motivation would be the assertion of control over doctrine. Putting the supernatural Lord Jesus on earth allowed the author to choose which teachings to put in the mouth of the messiah, thereby establishing them as divinely-ordained; and which to ignore or disparage. Beyond that, it gave the author the opportunity to deeply influence the reputations of the founders of the religion, deciding who to portray heroically, who to malign, and who to studiously avoid mentioning. We have seen that Christianity was deeply divided from its earliest days between the fanatical Essene Jews who founded the religion and began the Jerusalem church, and those who followed their “enemy” Paul whose communities of Gentile believers dotted Asia Minor, Greece, and beyond. It was Paul’s successors who gained an upper hand by avoiding the utter destruction of the recent war. And it seems that it was also a follower of Paul who penned the first gospel13Eisenman, R.H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin.—what we know today as The Gospel of Mark.

Possible Setting and Authorship

Scholars generally believe that the first gospel was composed by a Gentile writing in Greek (using occasional Latinisms), that he used a Greek translation of the Hebrew scriptures as a reference, and that he was writing for a Gentile audience. Although its place of composition can’t be known with certainty, many have suggested Rome.14Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2024, January 25). Gospel According to Mark. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Gospel-According-to-Mark The identity of the author can only be speculated at, though one intriguing possibility is that it was composed by the same Epaphroditus who was a “friend and fellow-worker”15Philippians 2:25. The Bible. New International Version. of the apostle Paul, had been the secretary of letters under emperor Nero, and then was the publisher of the works of Flavius Josephus. As a Gentile Christian author connected at the highest levels of imperial power, he is certainly a good candidate.16Eisenman, R.H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin.

John and Baptism

The first gospel says nothing whatsoever of Jesus’s birth. We are introduced to him as an adult who is said to come from Nazareth in Galilee.17Mark 1:9. The Bible. New International Version. This choice of a hometown for Jesus is possibly a corruption of the term “Nazirite”, which, as we have seen, described a kind of vow that was popular among the Essene Jews and early Christians. Or it may have been an interpretation of the term “Nazorean” which was a self-designation used among certain early Christians in Judah and surrounding areas for centuries18Eisenman, R.H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin.. Years later, the writer of the third gospel seems to interpret it this way, claiming that Jesus being from Nazareth is the fulfillment of a scriptural prophecy stating “He will be a Nazorean”19Matthew 2:23. The Bible. New International Version.—though there is no known scriptural passage which states this “prophecy”. The placement of his hometown in the region of Galilee may have been inspired by Isaiah 9 which includes the phrase “in the future he will honor Galilee of the Gentiles”. This same phrase “Galilee of the Gentiles” is used by the author later on in the gospel.

Before Jesus himself is introduced, however, the first character we meet in the first gospel is John the Baptist. John is said to be preaching to the crowds that have come to see him and receive his baptism. To introduce him, the writer quotes the same passage from Isaiah that was of such importance to the Essene writers of the Dead Sea Scrolls, about preparing a way for the Lord in the desert. In his only other line of dialogue, John plays down his own importance by saying that someone more powerful and important is coming who will baptize people with the holy spirit. This is when Jesus himself arrives on the scene and is baptized. As he comes out of the water, Jesus sees the skies split apart and the Holy Spirit descend on him like a dove while a voice from heaven says, “You are my beloved son. And I am pleased with you”—a quote mixing lines from Psalms 2 and Isaiah 42.20Mark 1-11. The Bible. New International Version. The function of this scene appears to be threefold:

- It creates a foundational historical model for the sacrament of baptism, which until now had been missing from Christian literature. We’ve seen that Paul had already created something of a foundation story for the Eucharist ritual involving the heavenly Lord Jesus. We’ve also suggested that Jesus’s heavenly crucifixion may have originated as an exemplar story for Essene rebels ready to become martyrs in an End Time battle against Rome. But until this point in history, no writer had supplied an equivalent establishing story for the Christian baptism ritual.

- Though John is referred to as a “good and holy man”, another purpose of this scene may have been to put John in his place. We know that the historical John the Baptist had his own communities of followers who revered him as God’s most important prophet.22Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2024, January 26). Mandaeanism. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Mandaeanism This story may be taking direct aim at this rival Jewish sect, or it may simply be an attempt by the Gentile author to temper the great esteem in which the fanatically-strict Essene Jew was held within the churches founded by the original apostles in Judah.

- The third purpose of the scene is more obvious: here God gives his unmistakable endorsement of Jesus. This stands out because, unlike stories from the Hebrew Bible where this (presumably) same God plays an extremely active role in human affairs, and has a great many lines of dialogue, this is not the case at all in the gospels or Acts. In fact, this baptism scene contains one of God’s mere two lines of dialogue in the entire gospel, fully endorsing Jesus as his son. And even so, he does this rather oddly, by recycling his own words from the Hebrew scriptures rather than saying anything original.

This presentation of Jesus as being vouched for by God and given the Holy Spirit only at his baptism would later inspire some Christian readers of this gospel to accept the doctrine of Adoptionism. This is the belief which holds that Jesus was not always the son of God, but was an ordinary (though extremely righteous) human until his adoption by God as his son at Jesus’s baptism—or, in other variations, at his resurrection, or his ascension.23Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. Apdotionism. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Adoptionism

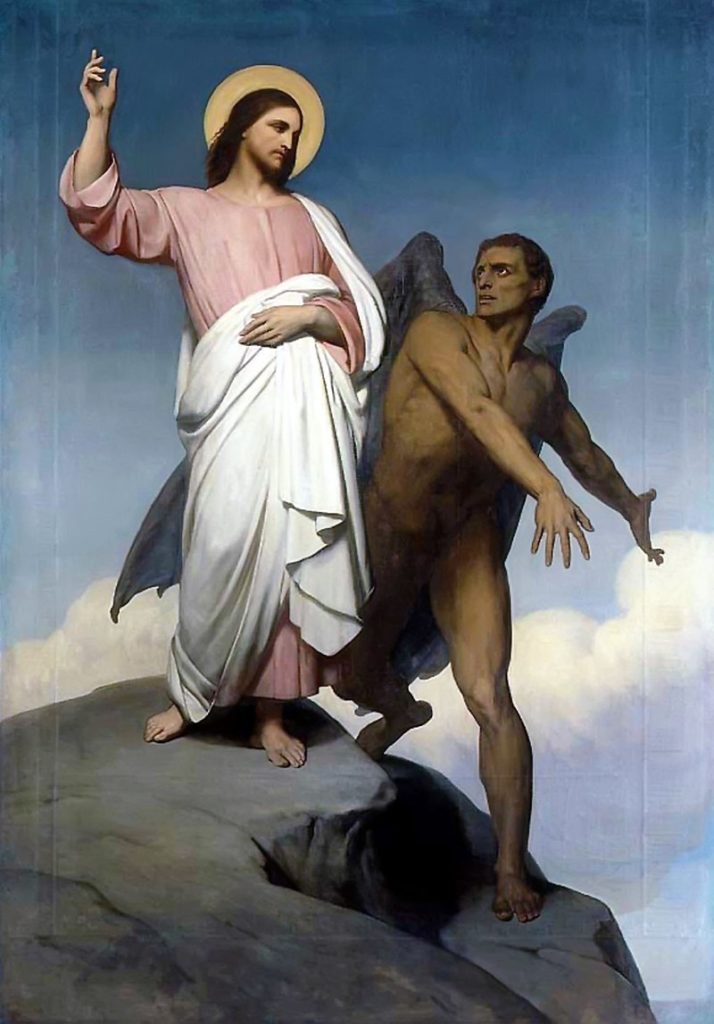

In comparison to later gospels, the first gospel is comparatively brief, and the storytelling significantly more concise. The author also seems to rush from one story to the next. The word “immediately” is used as a segue 41 times. Just at the moment God finishes speaking at his son’s baptism, immediately the Spirit drives Jesus into the desert to endure temptations from Satan for 40 days. Nothing whatsoever is said of these temptations, what they were, why they occurred, or what their outcome was. We can only note that Satan’s active role in the world mirrors the beliefs of the Essenes and their many doctrines imported from Zoroastrianism; and perhaps also that time spent in the desert under temptation is suggestive of the Essene initiation rituals likely undergone by Peter and James, and possibly Paul and Flavius Josephus as well.

Galilean Ministry

Jesus then goes to Galilee where he proclaims the gospel, and urges people to repent and believe the good news. Despite Jesus not explaining what this “gospel” even is, four fishermen drop what they’re doing and immediately become his devoted disciples. These include James, Peter, and John24Mark 14-20. The Bible. New International Version.—seemingly the same three men Paul had labeled as the three pillars of the Jerusalem church. Outside of this gospel, we have no reason to suspect these men were ever actually Galilean fishermen, and their portrayal here as rural bumpkins likely reflects Paul’s antagonism toward them, and is intended to undermine their reputation—as much else in this gospel also attempts to do.25Eisenman, R.H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin. Jesus then begins teaching in synagogues. His words are said to leave the people amazed, yet the reader is not even told what it was he taught them.26Mark 1:21-22. The Bible. New International Version.

At this point Jesus’s miracles begin. A man in the synagogue who is possessed by an evil spirit comes forward and shouts “Leave us alone, Jesus the Nazarene! Have you come to destroy us? I know who you are—the Holy One of God!” Jesus rebukes it to be silent and to leave the man, which it does. This introduces another theme in this gospel, which is that only supernatural beings fully understand who Jesus is. The people in the synagogue are amazed that this man has control over evil spirits, and this news quickly travels around Galilee.27Mark 1:23-28. The Bible. New International Version. Jesus’s various exorcisms in the gospel serve to establish his credentials as the Son of God and also provide readers with a foretaste of his ultimate victory over Satan—and all the forces of darkness—when he appears in glory in the Last Days.

Jesus then travels throughout Galilee, preaching, exorcizing more demons, and performing many miraculous healings of the blind, lame, deaf, mute, paralyzed, and even the dead. Besides merely demonstrating his powers, the author of the first gospel seems to have included these healings based on another out-of-context perceived ”prophecy” concerning the messiah from the book of Isaiah, stating, “God is coming to your salvation, coming to punish your enemies. The blind will see, the deaf will hear, and the lame will leap and dance, and the mute will shout for joy.” The anonymous writer of the third gospel—traditionally known as Matthew—recognizes this. When John the Baptist hears reports of this and all these miracles being performed, he sends messengers to ask Jesus who he truly is. Jesus sends his disciples back to him with his answer, instructing them to say, “Go and share what you have seen: the blind receive their sight and the lame walk, lepers are cleansed and the deaf hear, and the dead are raised up”. The author thus presents Jesus and John as sharing the same peculiar (Essene) interpretations of the Hebrew scriptures.

Jesus’s fame spreads throughout the land. In a nod to the scriptural stories of the Israelites following the miracle-working Moses through the desert, huge crowds now follow Jesus through the wilderness as he performs his own sets of miracles. Unlike the long speeches that will be added by later gospels, the first gospel contains no sermons on the plain, the mount, or anywhere. Here, Jesus’s public teachings come almost entirely in parables. This was likely inspired by yet more out-of-context quotes from the Prophets interpreted as relating to the messiah. In Ezekiel we find the verse, “Son of man, tell a riddle, and speak a parable to the house of Israel,”28Ezekiel 17:2. The Bible. New International Version. and “They say of me ‘Isn’t he a speaker of parables?”29Ezekiel 20:49. The Bible. New International Version. Inspiration may also have been found in a verse from Psalms: “I will open my mouth in parable.”30Psalm 78:2. The Bible. New International Version.

Written by a disciple of Paul for a Gentile audience, the author is motivated to enshrine Paul’s doctrines while continuously disparaging the “pillars” of the Jerusalem church and their doctrines. Despite traveling around with Jesus as his closest confidants, the disciples are depicted as failing to understand their messiah at every turn, and are portrayed as fickle fools.31Eisenman, R.H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin. In a powerful rebuke, Jesus at one point refers to Peter as Satan.32Mark 8:33. The Bible. New International Version. James, Peter, and John are shown as unreliable disciples when Jesus tells them to keep watch at the Garden of Gethsemane, and they fail him by falling asleep.33Mark 14:33-41. The Bible. New International Version. Most damningly, Peter three times denies even knowing Jesus on the night he is arrested,34Mark 14:66-72. The Bible. New International Version. and from that point until the end of this first gospel, the disciples’ reputations are not rehabilitated—in fact, they don’t appear in the story again. The last action that the disciples take in the first gospel is to abandon Jesus.

The Essenes and first Christians of James’s community were obsessed with obeying every facet of the Law of Moses, whereas their “enemy” Paul taught that the Law was a burden no longer required for salvation through Jesus Christ. In a move that would have outraged James’s church, the author of the first gospel portrays Jesus sharing meals with “unclean” Gentiles—even the hated tax collectors who collaborated with the Roman authorities—and other sinners.35Mark 2:15-16. The Bible. New International Version. Jesus is depicted as breaking the laws of the Sabbath,36Mark 2:23-28. The Bible. New International Version. some of the most sacred and important laws of the Jews, particularly the Essenes. Boldest of all, the gospel has Jesus dismiss the Jew’s food laws entirely, declaring that nothing that goes into a person can defile them, and declaring all foods clean.37Mark 7:14-15. The Bible. New International Version. Clearly this gospel passage is based on Paul’s teachings, rather than Paul’s teachings having been based on anything a historical Jesus said. For if a historical Jesus had made such a straightforward and momentous declaration, there would have been no need for Paul to then devote pages upon pages in his letters attempting to justify his position on this matter when he could have simply quoted the messiah himself and been done with it.

The author of the first gospel then becomes the first ever writer to posit that Jesus had a human family. While he is teaching and surrounded by a large crowd in Nazareth, we are told that Jesus’s mother and brothers have come to see him. We are told nothing about these family members, for the author seemingly introduces them only so that Jesus can dismiss them as worthless to him. When the messiah is told that his family is here to see him, but can’t reach him through the crowds, Jesus does nothing to help them. He shuns them completely, saying, “Who are my mother and my brothers? Here are my mother and my brothers! Whoever does God’s will is my brother and sister and mother.”38Mark 3:31-35. The Bible. New International Version. The only thing we are told about these family members is that they accuse Jesus of being “out of his mind”, while others nearby accuse him of being possessed by Satan.39Mark 3:20-22. The Bible. New International Version.

On a later second visit to Nazareth, Jesus offends the locals with his preaching, leading them to ask who this man thinks he is. “Isn’t he Mary’s son?” they ask—marking the only time in the first gospel that his mother is named. “Isn’t this the builder?” they ask.40Mark 6:2-3. The Bible. New International Version. The Greek word tekton, often translated as “carpenter”, actually indicates an unspecified type of constructor,41Tabor, J. (2017). Was Jesus a Carpenter? Taborblog. https://jamestabor.com/was-jesus-a-carpenter/ and may well have been intended by the author to show the locals’ inability to see Jesus as the ultimate “builder”—the pre-existent Son of God through whom God constructed the whole world. This is one of many episodes in the gospel in which the author portrays the Jews, as a whole, as being fundamentally unable to understand who Jesus really is, while those who do understand—primarily the Gentiles—are presented as the true inheritors of the salvation Jesus promises to those who have faith in him.

As a Gentile writer, likely in Rome, the author consistently demonstrates a poor understanding of the geography of Judah and its surroundings, having characters take wildly inefficient routes between cities,42Nineham, D.E. (1992). The Gospel of St. Mark. Penguin. and having Jesus cast 2,000 demon-possessed pigs over a cliff into “the sea” at a town that is 20 miles inland.43Mark 5:1-17. The Bible. New International Version. Two of his miracle stories are also set at sea on what the author refers to as the “Sea of Galilee”, but which is actually a relatively small freshwater body of water known today as Lake Tiberias.44Davidson, P. (2016. Did Mark Invent the Sea of Galilee? Is That In the Bible? https://isthatinthebible.wordpress.com/2016/08/29/did-mark-invent-the-sea-of-galilee/ Both stories—the stilling of the storm and Jesus walking on water—don’t just showcase the messiah’s godlike abilities, but are another opportunity for his Jewish disciples to be exposed as dolts who fail to comprehend Jesus’s teaching and the implications of the many miracles they are witnessing. “Do you still have no faith?” asks Jesus, expressing his disappointment in them.45Mark 4:40-41. The Bible. New International Version.

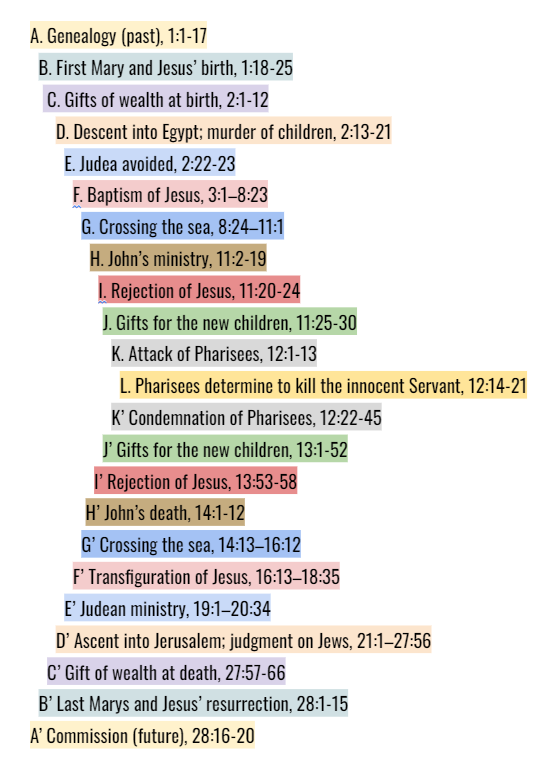

The two miracles at sea are matched by two miraculous feedings of massive crowds with only a small amount of food. These sets of similar stories in twos comprise part of what literary analysts recognize as an elegant “chiastic” structure to the first gospel. The basic idea behind this technique is to create mirror symmetry in one’s writing. If the work begins with Story A, Story B, Story C, and Story D, it will then follow with a story similar to Story C, then a story similar to Story B, and then a story similar to Story A. The number of stories involved can vary, and the first gospel even has chiastic sequences inside of larger chiastic sequences. Such contrived artifice is, of course, far more likely to be a way to aesthetically present a fictional narrative rather than a way to present remembered history.46Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press.

The scene in which Jesus takes the three “pillars” James, Peter, and John up a high mountain and becomes transfigured—such that his clothing glows dazzlingly white—is intended to show that Jesus is greater even than Moses who had a similar transfiguration experience in Exodus. Here Moses and Elijah appear and converse with Jesus, while Peter, uncomprehending as ever, suggests that tents should be set up for these visitors. For the second and last time, God himself speaks in the first gospel, saying, “This is my Son, the beloved. Listen to him,” which is not much more than he said at the baptism by John, and is again simply two separate quotes of Hebrew Bible passages stitched together.47Mark 9:1-8. The Bible. New International Version.

The entire first generation of Essene Jewish believers in Lord Jesus are disparaged in the next story in which, try as they might, the disciples cannot remove a dangerous demon from a young man. Jesus castigates them, saying “You unbelieving generation! How much longer must I endure with you?”48Mark 9:17-19. The Bible. New International Version. The unstated implication is very likely that Paul’s second generation of Gentile Christians was the first to truly believe in Jesus. The story that follows has the disciples arguing between themselves over who among them is the greatest. Jesus warns them that “he who wants to be first must make himself last”,49Mark 9:33-35. The Bible. New International Version. disparaging the disciples as egotists and echoing Paul’s argument that he alone had the true gospel of Lord Christ even though he was the last apostle that Jesus appeared to.

Not long after this, the author has Jesus tell his disciples, “If anyone causes one of these little ones—those who believe in me—to stumble, it would be better for them if a large millstone were hung around their neck and they were thrown into the sea.”50Mark 9:42-43. The Bible. New International Version. This is the latter half of a quote from the Epistle of Clement to the Corinthians, which the author must have had in his possession in addition to the epistles of Paul. The full quote reads, “‘Woe to that man! It would have been good for him not to be born, rather than cause one of my chosen to stumble. Better for him to have a millstone cast about his neck and be drowned in the sea than to have corrupted one of my little ones.”51Clement. First Epistle of Clement to the Corinthians. Early Christian Writings. https://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/1clement-lightfoot.html. The author of the first gospel takes a free hand in dividing the latter part of the quote from the first part which he uses later in the Last Supper scene in order to have Jesus describe the man who would betray him.52Mark 14:20-21. The Bible. New International Version.

Although the original Essene Jews who founded Christianity are routinely mocked and denigrated in the first gospel, some tenets of the Essene sect—presumably ones that did not contradict Paul’s beliefs—did survive into early Christianity. This can be seen in the story of a rich man who comes to Jesus and says he has kept all of God’s commandments since he was a boy. Jesus tells him that he nonetheless lacks one thing: he must “sell all his possessions and give the money to the poor.”53Mark 10:17-21. The Bible. New International Version. This same phrase “The Poor” is known to us as a self-designation among the Essenes, and may reflect their community’s foundational rule that any initiate must give all their money and possessions to the bishop of the community who would distribute it according to need. It is very likely that the earliest Christians in Judah practiced this communal living policy as well. The book of Acts contains an early scene in which we are told that all believers share their possessions in common, selling all they own and giving the money to the apostles for redistribution according to need.54Acts 4:32-35. The Bible. New International Version. Peter then castigates two believers who hand over most—but not quite all—of their wealth to the apostles, and immediately after being reproached, they each fall dead at Peter’s feet.55Acts 5:1-11. The Bible. New International Version. “How difficult it is for the rich to enter the kingdom of God!” muses Jesus in the first gospel, then adding: “It is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich person to enter the kingdom of God.”56Mark 10:23-26. The Bible. New International Version.

Jesus in Jerusalem

The last third of the gospel is set in Jerusalem. Clearly inspired by a verse from Zechariah reading, “Rejoice greatly, Daughter Zion! Shout, Daughter Jerusalem! See, your king comes to you, righteous and victorious, lowly and riding on a donkey, on a colt, the foal of a donkey”,57Zechariah 9:9. The Bible. New International Version. the author has Jesus arrive in the holy city to cheers, riding on a donkey.58Mark 11:1-9. The Bible. New International Version. In reality, as we have seen, the Romans were, at this time, on high alert for the outbreak of any displays of messianic fervor, and it strains credulity—if this were historical—that they would not have put a swift and violent end to pageantry such as this.

Jesus heads into the Temple where he observes the routine exchange of money for animals to offer to God as sacrifice, as well as the money changers who perform the necessary task of converting foreign coins into local currency to keep the Temple functioning normally. Inexplicably, Jesus is portrayed as having a tantrum in which he flips over tables and keeps anyone from carrying any of their purchases through the Temple courtyards.59Mark 11:15-17. The Bible. New International Version. These courtyards were far too expansive for a single man to have taken control of, and again: this area was heavily patrolled by Roman soldiers on the lookout for any disturbances, who would have taken quick and decisive action had this event actually occurred. But as with the rest of this gospel, we are dealing with fictional narrative rather than remembered history. While it is possible that the author considered this episode as a Christian rejection of traditional Jewish worship, it seems more likely that it’s simply another story entirely inspired by a combination of two out-of-context verses from scripture. Jesus himself quotes them both during the scene, saying, “Is it not written ‘My house will be called a house of prayer for all nations’?60Isaiah 56:7. The Bible. New International Version. But you have made it ‘a den of robbers.’”61Jeremiah 7:11. The Bible. New International Version.

Another major theme of the first gospel is the promotion of Paul’s pro-Roman, anti-revolutionary stance and the deprecation of the militant anti-Roman bent of the original Christians of James’s church in Jerusalem. It was the Tax Revolt led by Judas the Galilean in 6 CE that kicked off the rebellion against Roman occupation that would eventually culminate in the Jewish-Rome War in 66 CE. The author of the first gospel has the Pharisees in Jerusalem ask Jesus whether it is right to pay the imperial tax to Rome. Jesus’s reply is subtle and diplomatic: “Give back to Caesar what is Caesar’s, and give to God what is God’s.”62Mark 12:13-17. The Bible. New International Version. Unlike the mass of Jewish rebels who saw religious and secular matters as one and the same, the author here separates the two, having Jesus endorsing the acceptance of secular subjection to Roman authority.

In the next scene, the author has Jesus retrospectively “predict” the destruction of the Temple and Jerusalem, saying, “Do you see all these great buildings? Not one stone will be left on another here. Every one will be thrown down.”63Mark 13:1-2. The Bible. New International Version. He then takes his disciples to the Mount of Olives, the same spot overlooking the city where the Romans had established one of their war camps. There Jesus describes the events of the Last Days including false messiahs performing miracles, wars, earthquakes, persecutions, family members betraying one another. “How awful it will be in those days for pregnant women and nursing mothers!” he muses. Inspired by a passage in Isaiah—or its elaboration in the book of Revelation—Jesus declares that the sun and moon will go dark and the stars will fall from the sky. Finally, the Son of Man will come on the clouds with his army of angels.64Mark 13:3-27. The Bible. New International Version.

Jesus then stresses that these things will happen while some members of “this generation” are still alive.65Mark 13:30. The Bible. New International Version. This is an odd statement for the author to put in the mouth of Jesus two generations after the time of men like Peter and James. Although some of the original apostles may have lived to see the cataclysm of the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 AD, the longed-for and prophesied arrival of the Son of Man on the clouds with an army of angels never materialized during the war. Perhaps the author intended the reader to interpret the phrase “this generation” as the generation of the author himself? Either way it shows that by around 80 CE, the same expectation of the imminent End that motivated Paul’s preaching—and that of the earliest Christians before him—was still going strong. Despite 50 years having passed since Peter’s original vision of Lord Christ, this first gospel makes no attempt to explain the delay of the Last Days. It even goes so far as to have Jesus state that God has, for the sake of the disciples, shortened the amount of time it will take to arrive!66Mark 13:20. The Bible. New International Version.

Soon after Jesus’s description of the End Time, the author portrays one of the disciples named Judas Iscariot as seeking out the chief priests in order to betray Jesus.67Mark 14:10-11. The Bible. New International Version. Little is known of this Judas Iscariot character who, like so much in this first gospel, has never been mentioned by any early Christian writing before this—despite the certain infamy he would have garnered if he were an actual historical figure. His very name seem to be a construct with “Judas” meaning essentially “Jewish”, and “Iscariot” often seen by scholars as a corruption of “sicarii”—the fanatical Jewish rebel assassins who played a large role in the recent war and the years leading up to it.68Gubar, Susan (2009). Judas: A Biography. New York City and London, England: W. W. Norton & Company. By this point it’s hardly surprising that the author’s pro-Roman, pacifist Jesus is betrayed by a representative of the faction that the author is continuously trying to denigrate, the violently anti-Roman Jewish rebels.

The Last Supper and Arrest

Paul’s ritual of the Lord’s Supper is now given an earthly precedent in the famous narrative in which Jesus presides over a Passover meal with his disciples.69Mark 14:17-25. The Bible. New International Version. It is difficult to even imagine this sequence as historical, since that would require a devout Jewish man guiding his closest followers in a symbolic ritual of eating his flesh and drinking his blood (two things anathema to Jews in general, and to Essenes especially). These scenario only make sense as a way to commune with a god—as in Paul’s version of the Eucharist and similar communal ritual meals among the other Salvation cults of the era.

After eating, Jesus leads his disciples to the Mount of Olives, and predicts that they will all abandon him. When Peter swears that he would never do such a thing, Jesus insists that Peter will disown him three times before morning. All the disciples then swear they will stand by Jesus even if it leads to their deaths. They then go to Gethsemane where Jesus, in his most human and vulnerable moment in the entire New Testament, says his “soul is overwhelmed with sorrow to the point of death.”70Mark 14:26-34. The Bible. New International Version.

Jesus tells the disciples to be alert and to stand watch as he goes off to pray. Falling to the ground, he addresses God, saying, “Father, for you all things are possible. Take this cup from me. Yet, not what I will, but what you will.” He then finds his disciples asleep. Twice more he goes to pray, and returns to find them asleep, disappointing him yet again. When Judas arrives with the chief priests and their armed thugs to arrest him, Jesus asks, “Have you come with swords and clubs to arrest me like you would arrest a rebel?”—once again differentiating himself from the fanatical militant Essenes who began the religion.71Mark 14:34-48. The Bible. New International Version.

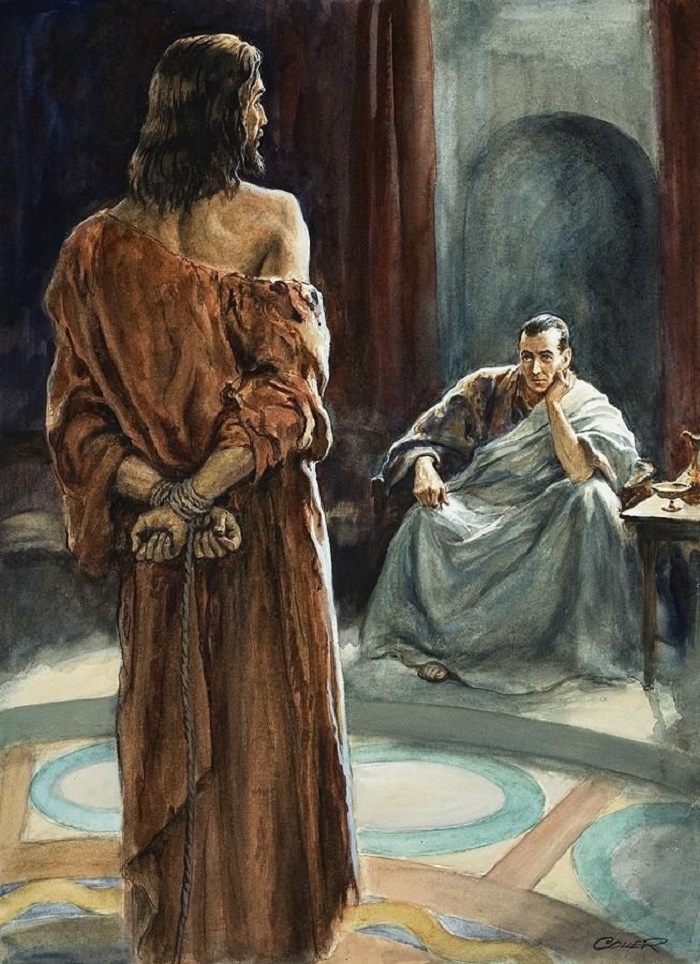

In what is almost certainly a narrative heavily influenced by the tale of Jesus Ben-Ananias told by Flavius Josephus in his book The Jewish War, Jesus of Nazareth is brought before the whole Jewish high court, the Sanhedrin. Although many accusations are made against him, Jesus remains silent and refuses to speak in his own defense. But finally when the high priest himself asks him, “Are you the messiah, the Son of the Blessed One?” Jesus announces, “I am, and you will see the Son of Man sitting at the right hand of the Power and coming with the clouds of heaven.” Outraged, they all declare him guilty of blasphemy and deserving death. Then, seemingly inspired by quotes from Micah 5 (“They shall smite the judge of Israel with a rod upon the cheek”) and Isaiah 50 (“I gave my back to scourges and my cheeks to blows, and I turned not away my face from the shame of spitting”), the high priest’s men begin to spit on him, blindfold him, and beat him.72Mark 14:53-65. The Bible. New International Version. Then they resolve to hand him over to the Roman governor Pilate for punishment.

There are multiple issues here if one were to take this as a historical event. There is no way the Sanhedrin would convene at night, much less on the night of a major holiday like Passover. If Jesus, or anybody, was convicted of blasphemy, Jewish law demanded his immediate execution by stoning. The Romans in this era granted the Sanhedrin the right to decide cases concerning religious matters and punish guilty Jews accordingly, even putting them to death. There would have been no reason to bother the Roman governor with such a matter, especially not in the middle of the night.73Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press.

Meanwhile, outside the Sanhedrin, Peter—the only disciple to follow Jesus after his arrest—denies knowing his teacher three times, as predicted, cementing his reputation as an unreliable coward and dimwit who never really understood Jesus’s significance or his teachings. In the last we hear of him in this first gospel, he breaks down and weeps at his own inconstancy.74Mark 14:66-72. The Bible. New International Version.

The Crucifixion

Brought before Pilate, the Jews repeat all their accusations about him. “Have you nothing to say?” the governor asks Jesus. But again, in the style of Jesus Ben-Ananias—who also came to the Temple to preach and predict its destruction before getting arrested and taken before the Roman governor—Jesus remains silent, refusing to defend himself.75Mark 15:1-5. The Bible. New International Version. Jesus’s silence may also derive in part from a passage from Isaiah 53, reading, “He was led as a sheep to the slaughter, and as a lamb before the shearer is dumb, so he opens not his mouth.”

At this point the author of the gospel seeks to drive home a point through the use of a plot contrivance: a so-called “custom”—with no possible basis in history76Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press.—in which, at Passover, the Romans offer the Jewish people a choice between two convicted criminals, one of whom is immediately set free. We are told that governor Pilate presents the people with a choice between Jesus, who, unbeknownst to them, is the actual Son of God; and a fanatical Jewish rebel who has committed murder during a recent insurrection, whose name is Barabbas (“Son of Father”). The Jews enthusiastically and unanimously shout their choice, and the violent revolutionary Barabbas goes free.77Mark 15:6-15. The Bible. New International Version.

They have made their catastrophic choice that will end with Jerusalem being destroyed and their being held responsible for murdering their own messiah. Pilate, known from history as a brutal and unforgiving oppressor, is reinvented by the author of the gospel as a reasonable and sympathetic man who has no wish to harm the innocent Jesus of Nazareth. Yet, for reasons unexplained, he does not exercise his authority to pardon him or mitigate his punishment, but instead simply gives into the crowd’s demands, and hands him over to be flogged before his crucifixion.78Mark 15:12-15. The Bible. New International Version.

This story, supremely unhistorical as it is, is elegantly constructed. In addition to its other messages, it mirrors the Jewish ritual set forth in Leviticus and enacted each year on Yom Kippur: two identical goats would be procured, and then while one was set free to roam the wild, the other would become a sacrifice on behalf of the entire people, atoning for their sins.79Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press.

Most of the details of the following climactic scene of the gospel—the crucifixion of Jesus—are clearly “known” to the author only through (yet more) out-of-context quotes of scripture. This was, of course, the very methodology that James and the Essenes—and Paul after them—used to discover information about the heavenly savior, and was now being employed to flesh out an earthly narrative of that same savior. A side-by-side comparison illustrates this clearly:

| Text of First Gospel | Scriptural Inspiration |

|---|---|

| They crucified him and divided his clothes, throwing dice for them, to decide what each would take. | They parted my garments among themselves, and cast lots upon my raiment. Psalms 22:19 |

| And they crucified two outlaws with him, one on his right and one on his left. | He willingly submitted to death and was numbered with the rebels. But he carried away the sins of many people, interceding for those who sinned. Isaiah 53:12 |

| They offered him wine mixed with myrrh, but he did not take it. | They gave me also gall for my food, and made me drink vinegar for my thirst. Psalms 69:22 |

| Those who passed by insulted him, shaking their heads.Likewise the chief priests and scribes mocked him. | All that saw me mocked me. They spoke with their lips, they shook the head. Psalms 22:8 I became an object of scorn to them. When they saw me they shook their heads. Psalms 109:25 |

| Women looked on from a distance. | My friends and companions stand aloof from my affliction, and my relatives stand afar off Psalms 38:11 |

| And at the ninth hour Jesus cried with a loud voice, saying, Eloi, Eloi, lama sabachthani? which is, being interpreted, My God, my God, why have you forsaken me? | My God, my God, why have you forsaken me? Psalm 22:1 |

| The sun went dark at noon as the Son of God died.80Mark 15:16-40. The Bible. New International Version. | On that day, says the Lord God, I will make the sun go down at noon and darken the earth in broad daylight…I will make it like the mourning for an only son. Amos 8:9-10 |

Is it possible that Jesus’s passion had a historical basis onto which all these scriptural elements were later added? In short, no. Rather than mere decoration, these scriptural references underpin the narrative. Remove them and you are left with incoherence. In addition, many details of the Passion story that are not based on scriptures—the nighttime Sanhedrin trial on Passover, Pilate as sympathetic ear to a Jewish messianic figure—strain credulity beyond the breaking point.81Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press.

Even in ancient times historians understood the need to relate to the reader how they came to know things, but the anonymous author of the first gospel never tells us their own connection to the people and events they describe. If they had multiple sources, they give no indication why one was favored over another—no sources at all are even hinted at. In fact, the narrative is not told the way a witness might tell it, but it is related from the standpoint of an omniscient observer—a hallmark of fictional writing. This allows us to know the thoughts of various characters and be privy to things a normal observer could not, like the dialogue from Jesus’s trials where no disciples were even with him.82Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press.

The Empty Tomb

The first gospel ends rather abruptly. Jesus’s body is placed in a tomb, and after three days, three women approach the tomb and see a young man dressed in white next to the opened tomb. He tells them Jesus has been raised and isn’t there. He orders them to tell the disciples in Galilee, and promises they will see Jesus there. But the women are so terrified and bewildered that they say nothing to anyone because of their fear.83Mark 16:1-8. The Bible. New International Version.

That’s it. That’s the ending. We can only guess the author’s intention in ending the story on that note. Was it meant as a final slight to the reputations of the original apostles by suggesting they were oblivious even to Jesus’s resurrection? Was it simply part of the gospel’s oft-repeated “tell no one about me” theme—a preemptive answer to the question “how did Jesus live on earth and we’ve never heard about it until now?” Later gospel writers clearly found the ending quite unsatisfactory, as each decided to change it in their own ways.84Note: At least one later influential church father found the ending of the first gospel so problematic that he composed a new ending for it, so as to bring it in line with the post-resurrection stories told in the later gospels. Though it still appears in many editions of the New Testament to this day, scholars universally recognize it as a later forgery.

Continue Reading:

Footnotes

- 1Mark 1:1. The Bible. New International Version.

- 2Ehrman, B. (2014). Why Are the Gospels Anonymous? The Bart Ehrman Blog. https://ehrmanblog.org/why-are-the-gospels-anonymous/

- 3Note: Most secular scholars date the first gospel after 70 CE, but not long after. I have seen no compelling argument that it could not be as late as approximately 80 CE, as the only constraint is that it must have been published and disseminated before the second gospel which uses great amounts of material from it.

- 4Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press.

- 5Hebrews 5:11-14. The Bible. New International Version.

- 6Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press.

- 7Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press.

- 8Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press.

- 9Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press.

- 10Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press.

- 11Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press.

- 12Mark 4:10-12. The Bible. New International Version.

- 13Eisenman, R.H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin.

- 14Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2024, January 25). Gospel According to Mark. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Gospel-According-to-Mark

- 15Philippians 2:25. The Bible. New International Version.

- 16Eisenman, R.H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin.

- 17Mark 1:9. The Bible. New International Version.

- 18Eisenman, R.H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin.

- 19Matthew 2:23. The Bible. New International Version.

- 20Mark 1-11. The Bible. New International Version.

- 21Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2024, January 26). Mandaeanism. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Mandaeanism

- 22Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2024, January 26). Mandaeanism. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Mandaeanism

- 23Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. Apdotionism. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Adoptionism

- 24Mark 14-20. The Bible. New International Version.

- 25Eisenman, R.H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin.

- 26Mark 1:21-22. The Bible. New International Version.

- 27Mark 1:23-28. The Bible. New International Version.

- 28Ezekiel 17:2. The Bible. New International Version.

- 29Ezekiel 20:49. The Bible. New International Version.

- 30Psalm 78:2. The Bible. New International Version.

- 31Eisenman, R.H. (1998). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin.

- 32Mark 8:33. The Bible. New International Version.

- 33Mark 14:33-41. The Bible. New International Version.

- 34Mark 14:66-72. The Bible. New International Version.

- 35Mark 2:15-16. The Bible. New International Version.

- 36Mark 2:23-28. The Bible. New International Version.

- 37Mark 7:14-15. The Bible. New International Version.

- 38Mark 3:31-35. The Bible. New International Version.

- 39Mark 3:20-22. The Bible. New International Version.

- 40Mark 6:2-3. The Bible. New International Version.

- 41Tabor, J. (2017). Was Jesus a Carpenter? Taborblog. https://jamestabor.com/was-jesus-a-carpenter/

- 42Nineham, D.E. (1992). The Gospel of St. Mark. Penguin.

- 43Mark 5:1-17. The Bible. New International Version.

- 44Davidson, P. (2016. Did Mark Invent the Sea of Galilee? Is That In the Bible? https://isthatinthebible.wordpress.com/2016/08/29/did-mark-invent-the-sea-of-galilee/

- 45Mark 4:40-41. The Bible. New International Version.

- 46Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press.

- 47Mark 9:1-8. The Bible. New International Version.

- 48Mark 9:17-19. The Bible. New International Version.

- 49Mark 9:33-35. The Bible. New International Version.

- 50Mark 9:42-43. The Bible. New International Version.

- 51Clement. First Epistle of Clement to the Corinthians. Early Christian Writings. https://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/1clement-lightfoot.html.

- 52Mark 14:20-21. The Bible. New International Version.

- 53Mark 10:17-21. The Bible. New International Version.

- 54Acts 4:32-35. The Bible. New International Version.

- 55Acts 5:1-11. The Bible. New International Version.

- 56

- 57Zechariah 9:9. The Bible. New International Version.

- 58Mark 11:1-9. The Bible. New International Version.

- 59Mark 11:15-17. The Bible. New International Version.

- 60Isaiah 56:7. The Bible. New International Version.

- 61Jeremiah 7:11. The Bible. New International Version.

- 62Mark 12:13-17. The Bible. New International Version.

- 63Mark 13:1-2. The Bible. New International Version.

- 64Mark 13:3-27. The Bible. New International Version.

- 65Mark 13:30. The Bible. New International Version.

- 66Mark 13:20. The Bible. New International Version.

- 67Mark 14:10-11. The Bible. New International Version.

- 68Gubar, Susan (2009). Judas: A Biography. New York City and London, England: W. W. Norton & Company.

- 69Mark 14:17-25. The Bible. New International Version.

- 70Mark 14:26-34. The Bible. New International Version.

- 71Mark 14:34-48. The Bible. New International Version.

- 72Mark 14:53-65. The Bible. New International Version.

- 73Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press.

- 74Mark 14:66-72. The Bible. New International Version.

- 75Mark 15:1-5. The Bible. New International Version.

- 76Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press.

- 77Mark 15:6-15. The Bible. New International Version.

- 78Mark 15:12-15. The Bible. New International Version.

- 79Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press.

- 80Mark 15:16-40. The Bible. New International Version.

- 81Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press.

- 82Carrier, R. (2015). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press.

- 83Mark 16:1-8. The Bible. New International Version.

- 84Note: At least one later influential church father found the ending of the first gospel so problematic that he composed a new ending for it, so as to bring it in line with the post-resurrection stories told in the later gospels. Though it still appears in many editions of the New Testament to this day, scholars universally recognize it as a later forgery.